As you have seen from the readings, the Ancient Greeks were concerned with an elaboration of the concepts of Matter, Being, and Becoming. Below is a history of the ideas of the Ancient Greek philosophers and their relation to the thinking in modern physics. These are notes to a history of the development of the Natural Sciences.

Thales and the Milesian School: “Water is the material cause of all things.”:

Expresses three fundamental ideas of philosophy:

- The question as to the material cause of all things: the “what” and the “how” of things

- The demand that the question be answered in conformity with reason without resort to myths or mysticism: the grounding of the principle of reason

- The postulate that ultimately it must be possible to reduce everything to one principle

Thales’ statement is the first expression of the idea of a fundamental substance of which all other things were transient forms (i.e. water as Being and the forms of things, Becoming). Rest and motion, the permanent and the transient were central issues for the Greeks.

“Substance” is not to be understood in the material sense. Life is inherent in this “substance”.

Aristotle ascribes to Thales the statement: “All things are full of gods.”

It may be best to consider Thales’ statement in a metaphysical sense, that is, the qualities and characteristics of water are the fundamental principles of all things (categories).

Anaximander:

Denies that the fundamental substance is water or any known substance.

The primary substance is infinite, eternal, and ageless (Being) and encompasses the world. This infinite substance undergoes no change.

The primary substance is transformed into the various substances that we see before us.

“Into that from which things take their rise they pass away once more, as is ordained, for they make reparation and satisfaction to one another for their injustice according to the ordering of time.”

Here we have the antithesis of Being and Becoming. The primary substance: the infinite, ageless, undifferentiated Being, degenerates into various forms which leads to endless struggles. Becoming is perceived as a debasement of infinite Being—a disintegration into the struggle ultimately expiated by a return into that which is without shape or character.

The struggle is the struggle of opposites: hot and cold, dry and moist. The temporary victory of one over another is the injustice for which they finally make reparation in the ordering of time. According to Anaximander there is “eternal motion”, the creation and passing away of worlds from infinity to infinity.

Relation to modern science: the physicists today try to find a fundamental law of motion for matter from which all elementary particles and their properties can be derived mathematically.

The fundamental equation of motion may refer to waves of a known type, to proton or meson waves, or to waves of an essentially different character which have nothing to do with any of the known waves or elementary particles.

First case: All other elementary particles can be reduced in some way to a few sorts of ‘fundamental’ elementary particles.

Second case: All different elementary particles could be reduced to some universal substance which we may call matter or energy, but none of the different particles could be preferred to the others as being more fundamental. The second case is similar to Anaximander. In general, quantum physicists hold this view.

Anaximenes: Air is the primary substance. “Just as our soul, being air, holds us together, so do breath and air encompass the whole world.”

Anaximenes says that ‘condensation’ causes the change of the primary substance into the other substances.

Heraclitus of Ephesus: the concept of Becoming

That which moves, the fire, is the basic element

The difficulty: to reconcile the idea of one fundamental principle with the infinite variety of phenomena is solved by recognizing that the strife of opposites is really a kind of harmony.

The world is a ‘one and a many’ and it is the opposite tension of the opposites that constitutes the unity of the One.

“We must know that war is common to all and strife is justice, and that all things come into being and pass away through strife.”

We can see that ancient pre-Socratic Greek philosophy deals with the question of the “One and the Many”

For our senses, the world consists of an infinite variety of things and events, colours, sounds. In order for it to be understood, we must impose some kind of order, and order means what is equal, to make something a unity. This is called the mathematical projection. From this springs the need and search for one fundamental principle to account for the infinite variety of things.

Since the world appears to be made of matter, a material cause of all things was looked for.

From this comes the idea of the undifferentiated Being, whether material or not, to attempt to explain the infinite variety of things.

This leads to the antithesis of Being and Becoming and finally to Heraclitus’ solution: change is the fundamental principle. Change itself is not a material cause and therefore it is represented by Heraclitus as the fire, the basic element, which is both matter and a moving force.

This is very close to modern science: if we replace fire with “energy” we can almost repeat Heraclitus’ statements word for word.

“Energy” is the substance from which all elementary particles, all atoms and therefore all things, are made.

Energy is that which moves. Energy is a substance since its total amount does not change and the elementary particles can be made from this

“Energy” is the substance from which all elementary particles, all atoms and therefore all things, are made.

Energy is that which moves. Energy is a substance since its total amount does not change and the elementary particles can be made from this substance as is seen in many experiments.

Energy can be changed into motion, heat, light and tension.

Parmenides: the concept of the One

“One cannot know what is not – that is impossible – nor utter it; for it is the same thing that can be thought and that can be.”

For Parmenides, there is only the One and there is no becoming or passing away. Parmenides denies the existence of empty space for logical reasons. Since change requires empty space, he dismissed change as an illusion. Parmenides presents a paradox.

Empedocles: the shift from materialism to dualism.

There are four elements: earth, air, fire, water. The elements are mixed together and separated by the actions of Love and Strife. Love and Strife are corporeal elements and responsible for imperishable change.

For Empedocles: there is the infinite Sphere of the One, but in this primary substance, Love has mixed all four elements. When Love is passing away, Strife enters and the elements are partially separated and partially combined. After that, the elements are completely separated and Love is outside the World. Finally, Love is bringing the elements together again and Strife is passing out, so that we return to the original Sphere.

Empedocles: the four elements are not so much fundamental principles as real material substances. The mixture and separation of a few substances explains the infinite variety of things and events. While it does not satisfy those who wish to think in fundamental principles, it is a reasonable kind of compromise which avoids the difficulties of a monistic view and allows the establishment of some order.

Anaxagoras: all change is caused by mixture and separation. All things are composed of small “seeds” and this allows for a geometrical interpretation of the term “mixture”: see two sands of different colours and relative positions, and the number of grains may change but they are held in ‘proportion’ in one thing or another.

“All things will be in everything; nor is it possible for them to be apart, but all things have a portion of everything.”

The universe of Anaxagoras is set in motion not by Love and Strife but by “Nous” which is translated “Mind”.

From Anaxagoras’ seeds, it is a small step to the concept of the atom of Leucippus and Democritus.

The antithesis of Being and Not-being in Parmenides is made into the “Full” and the “Void”.

Being is not only One, it can be repeated an infinite number of times. This is the atom, the indivisible smallest unit of matter. The atom is eternal and indestructible, but it is finite in size. Motion is made possible by the empty space between atoms. This is the first time that a concept of the smallest ultimate particle as the fundamental building block of matter is expressed.

Democritus’ atom consists not only of the “Full”,but also of the “Void” of empty space in which the atoms move. The logical objection of Parmenides against the Void, the not-being did not exist, is rejected to comply with experience.

From the modern point of view, the empty space between atoms is not nothing; it is the carrier for geometry making possible the various movements of the atoms. In the theory of general relativity, the answer is that geometry is produced by matter or matter by geometry.

This corresponds to the view of many philosophers that space is the extension of matter. But Democritus departs from this view to make change and motion possible.

The atoms of Democritus are all of the same substance, have the property of being, and have different sizes and shapes.

They were pictured as divisible mathematically, but not in a physical sense.

The atoms could move and occupy different positions in space, but they have no other physical properties.

They have no sensible qualities: sense, smell, taste.

The properties of atoms that we perceive with our senses are supposedly produced by the movements and positions of the atoms in space.

Just as tragedy and comedy can be written by using the language of the alphabet, the vast variety of events/experiences/things in the world are realized by the same atoms through their different arrangements and movements.

Geometry and the study of motion (I.e. the study of space and time) are made possible by the Void.

“A thing merely appears to have colour, it merely appears to be sweet or bitter. Only atoms and empty space have a real existence.” –quote attributed to Democritus

“Nothing happens for nothing, but everything from a ground and of necessity.” – Leucippus

The atomists see everything as a causality; causality can only explain later events by earlier events, but it can never explain the beginning.

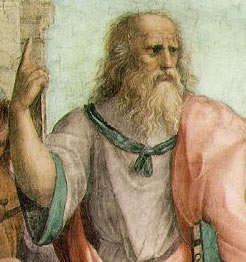

Plato: The Timaeus.

Plato was not an atomist; Plato disliked Democritus so much that he thought all of his books should be burned. But Plato combines ideas near to the atomists with those of the Pythagoreans and the teachings of Empedocles.

The Pythagorean school: an offshoot of Orphism which goes back to the worship of Dionysus. There is an establishment of a connection between religion and mathematics. Pythagoreans were the first to realize the creative force inherent in mathematical formulations.

The Pythagoreans discovered that two strings sound in harmony if their lengths are in a simple ratio. For the Pythagoreans, the simple mathematical ratio between the length of the strings created the harmony in sound.

Plato knew of the discovery of regular solids made by the Pythagoreans and of the possibility of combining them with the elements of Empedocles. Earth=cube, air=octahedron, fire=tetrahedron, water=icosahedron. There is no element that corresponds to the dodecahedron; here Plato says: “There was a fifth combination which the God used in his delineation of the universe.”

If the regular solids, which represent the four elements, can be compared to atoms at all, it is clear in Plato that they are not indivisible. Plato constructs the regular solids from two basic triangles: the equilateral and the isosceles, which when put together form the surface of solids.

The elements can be partly transformed into each other. The regular solids can be taken apart into their triangles and new regular solids can be formed of them. Ex: one tetrahedron and two octahedron can be taken apart into 20 equilateral triangles which can be recombined to form one icosahedron. That means: one atom of fire and two atoms of air can be combined to give one atom of water.

But the fundamental triangles cannot be considered as matter as they do not have extension in space. It is only when the triangles are put together to form a regular solid that a unit of matter is created.

- The smallest parts of matter are not the fundamental Beings, as in the philosophy of Democritus, but are the mathematical forms.

- The form is more important than the substance of which it is the form since it is the form that brings the thing to presence.

Comparison of Ancient Greek and Modern Science:

- There might be some confusion over the use of the word “atom”. Democritus’ atoms should be compared to the elementary particles: the proton, neutron, electron, and meson.

- Democritus was well aware that atoms do not have the properties of colour, taste and smell but their motion and arrangement explain these properties. The atom is an abstract piece of matter.

- The atom does have the quality of “being”: extension in space, shape and motion. Democritus leaves these qualities because it would have been difficult to speak about the atom at all if such qualities had been taken away. On the other hand, this implies that the concept of the atom cannot explain geometry, extension in space or existence because it cannot reduce them to something more fundamental (which explains, perhaps, why Plato might want to burn his books).

Let’s shift to the modern view: What is an elementary particle?

- “A neutron” but we can give no well-defined picture of what we mean by the word: a particle, a wave, a wave packet; but we know that none of these descriptions is accurate.

- The neutron has no colour, taste or smell. It resembles the atom of Greek philosophy.

- The concepts of geometry and motion, space and time, cannot be applied to it consistently.

If one wants to give an accurate description of the elementary particle-with an emphasis on the word ‘accurate’- the only thing that can be written down is a ‘probability function’. But then one sees that not even the ‘quality’ of being belongs to what is described. It is a possibility for being or a tendency for being (Aristotle). The elementary particle is far more abstract than that of the Greeks’ atom and it is this abstractness that may help it to explain the behaviour of matter.

In Democritus, all atoms consist of the same ‘substance’. The elementary particles of modern physics carry a mass in the same limited sense that they have other properties.

Since mass and energy are, according to the theory of relativity, essentially the same concepts we can say that all elementary particles consist of energy. Ergo: energy is the primary substance of the world.

The views of modern physics are very close to Heraclitus: fire is energy; energy is that which moves; it is the primary cause of all change and energy can be transformed into matter, heat or light. The strife of opposites in Heraclitus can be found in the strife between two different forms of energy.

For Democritus, the atoms are eternal and indestructible units of matter which can never be transformed into each other.

Modern physics stands with Plato and the Pythagoreans and against the materialism of Democritus on this issue.

The elementary particles can be transformed into each other. Two elementary particles moving through space at a very high velocity, collide, and create many new elementary particles from the available energy and the old particles have disappeared in the collision.

The elementary particles in Plato’s Timaeus are finally not ‘substance’ but mathematical forms. “All things are numbers” according to Pythagoras.

In modern physics, the elementary particles will finally also be mathematical forms, but of a much more complicated nature than the Pythagorean triangles.

The Greeks thought of static forms and found them in the regular solids. Modern science, since Newton, is concerned with the dynamic problem, the creation of a ‘law of motion’. Newton’s law of motion holds at all times, it is in this sense eternal, whereas the geometrical forms, like the orbits, are changing.

The mathematical forms that represent the elementary particles will be the solution of some eternal law of motion for matter. This is a problem which has not been solved.

Heisenberg: “The final equation of motion for matter will probably be some quantized nonlinear wave equation for a field of operators that simply represents matter, not any specified kind of waves or particles….the fundamental equation for matter [will follow] by much the same mathematical process by which the harmonic vibrations of the Pythagorean string follow from the differential equation of the string.”

The final fundamental equation should result in a “simple” (Heisenberg’s words) mathematical formula. “This fact fits in with the Pythagorean religion, and many physicists share their belief in this respect…”

WARNING: There is an enormous difference between modern science and Greek philosophy and the difference is the empiricist attitude of modern science. Since Galileo and Newton, modern science has been based upon a detailed study of nature and upon the postulate that only such statements should be made as can be verified by experiment. The scientific method of Francis Bacon.

The idea that one could single out from nature a series of events by experiment in order to study the details and to find out the constant law in the continuous change did not occur to the Greek philosophers. Why?

When Plato says that the smallest particles of fire are tetrahedrons, it is difficult to see what he means. Is the form symbolic? Are they rigid or elastic? What force can separate them into equilateral triangles? (the mind?)

When modern science states that the proton is a certain solution of a fundamental equation of matter, it means that we can from this solution deduce mathematically all the possible properties of the proton and check the correctness of the solution by experiments in every detail.

The possibility of checking the correctness of a statement experimentally with very high precision and in any number of details gives enormous weight to the statement that could not be attached to the statements of early Greek philosophy.

The Greeks show that by combining our ordinary experience of nature with untiring efforts to get some logical order into this experience and to understand its general principles, this gets one far along the path to knowledge.

love this, simple reading, and super exciting. I love that you’ve gone one by one and made it so cool

LikeLike

Thank you. You are welcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person