TOK Questions: How has technology had an impact on collective memory and how knowledge is preserved? What is the difference between “data”, “information” and “knowledge”? To what extent is the internet changing what it means to know something? In what sense, if any, can a machine be said to know something? Does technology allow knowledge to reside outside of human knowers? Does technology just allow us to arrange existing knowledge in different ways, or is this arrangement itself knowledge in some sense? Have technological developments had the greatest impact on what we know,

how we know, or how we store knowledge?

Technology’s relation to ethics seems to be an obvious theme of inquiry in the modern age. We understand technology as a “doing” in many instances, a “know how”, a praxis. We use the word “technique” to indicate this practical doing. Artists and engineers have various techniques that they use to bring forth their “works”. We confuse the tools and instruments of technology with the essence of technology itself for it is technology itself which has created the world-space which allows these tools and instruments to come into being. But what is this technology and what is its relation to knowledge and ethics?

All of our actions are attempts to achieve some “good end”, whether for ourselves or for others. Just as technology is the “know how” that attempts to achieve the good end in the “bringing forth” of things, the “production” of things, including knowledge, so too is ethics, properly understood, an attempt to achieve the good end through action, that “good end” being the “fittedness” for human beings of their actions. A motif that runs throughout Shakespeare’s Macbeth is how the character Macbeth tries to cloak himself in garments that are ill-fitting or not suited to him. The “fittedness” of something is related to “truth” both of the thing and the actions required to bring about the thing. It is also connected to what we understand as justice, “a rendering to someone what is their due” or what is “fit” for them.

The clearing of the ground of the assumptions that we have about what ethics are and the obfuscation that surrounds ethics in the modern can be put simply in a statement: modern human being does not know the difference between good and evil. In discussing Ethics, it is most important to clarify the viewing (perspectives) so that technology can be understood as a way of knowing and being-in-the-world. This understanding will, hopefully, open up the domain of that area that we call ethics which we hope will make clear that ethics are not the principles but the actions themselves as understood in the treatise of Aristotle from which the word“ethics” gets its origin.

In the new TOK Guide for 2022, technology itself is simply understood as an instrument or a tool and this understanding is not questioned. The uses of technology are the roots of the questions posed in attempting to understand the relation between technology and knowledge. To use the analogy that the Guide uses for what the inquiry into what knowledge is, it is technology itself which creates the map that allows the traveller to set out upon the journey to seek what knowledge itself is. Technology provides the legend (how we will understand and interpret the concepts) and the compass (the methodology) for how we will determine and undergo the search for knowledge.

In the thinking on technology that we have been concerned with in these writings about Theory Of Knowledge, we have discovered that our “understanding” of technology as instrument and as human activity, or a “means to an end”, is a notion so commonplace and prevalent in everything we say and do that this “understanding” has become self-evident. Such is the case with the new TOK Guide; what technology is is understood and there is no further need to question what technology itself is.

If we look closely, however, we can see that what we call “technology” is the Ethics; there is no separation of theory and practice here. This self-evident nature of technology, this commonplace understanding is, as we have come to understand it, a “correct” understanding, but it does not go far enough in reaching towards what technology is, what its essence is; that is, while it is “correct”, it is not the truth of what technology is, or rather, it is not the true nature of the situation we find ourselves in as knowers. When we are incapable of understanding the situation we find ourselves in, that way of being-in-the-world and thinking which the Greeks called phronesis is not sufficient to allow us to penetrate to the heart of what the situation is. Just as our modern conception of number prevents us from seeing the true nature of the mathematical, our understanding of technology deters us from finding its essence.

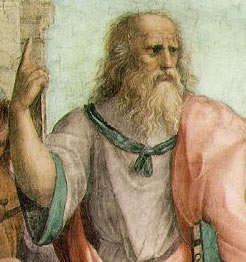

If we remember from our reading of the Cave in Bk. VII of Republic, ( Plato’s Allegory of the Cave ) for Plato the essence of something is not the same thing as the thing itself. In thinking of the essence of a tree, “that which pervades every tree, as tree, is not itself a tree that can be encountered among all the other trees. Likewise, the essence of technology is by no means anything technological.” (Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, tr. W. Lovitt (New York: Harper & Row, 1977 herein after referred to as QT, p. 4) The “un – usual” or “uncanny” nature of this situation, whereby we see no essential difference between modern technology and older forms of craftsmanship and agricultural methods, is due to technology’s framing nature. The instrumental definition of technology in a sense has blocked our access to the fundamental differences between modern machine technology and the older tools of farmers and craftsmen. This has happened as a result of Framing or, in German, Gestell. Technology is a way of knowing and a way of being in the world. The “knowing” (logos) precedes the “making” (techne: “the knowing one’s way about”, the praxis) that forms the root words “techne” and “logos” or “technology”. The logos is the gathering and the rendering of the techne, what we have come to understand as “methodology”. The Framing provides us with the perspective which gives us a “world-picture”, and this picture gives us our understanding of the situations and conditions which we find ourselves in.

In his essay on “The Question Concerning Technology” the German philosopher, Martin Heidegger, says that in order for us to understand technology we must proceed along the “path of thinking” which is illuminated for us in an “extraordinary manner” by language. We have language because we live in communities, and our living in communities, with others, requires ethics.

In giving ourselves to thinking, we do an activity which subverts much of what we take to be ordinary (and for many of you that has been, or should be, your experience of the TOK course: a subversion of what you take to be the ordinary, of what your assumptions and presuppositions are regarding what you know); the thinking leads us to the extra-ordinary, the extra-mundane. Thinking involves the privation of the usual, of the “normal”, the ‘un’-doing of what we take to be the usual.

In German, the root wohnlich means “homely”, something we are at-home-with and familiar with, and Heidegger likes to use this term regarding thinking. The root in turn of wohnlich is the verb wohnen – to live, to dwell, where we are at home. When we think that we drive and control the issues that arise from within technology itself, primarily the ethical issues, we fail to see the true nature of our comportment, our role, how our thinking proceeds, how one can properly answer the call of thinking and the kind of attention that is necessary to think. In thinking, rather than deluding ourselves with the idea that we can bend technology to our will, and lead it or drive it somewhere (what we call “progress”, the bringing about of the “good end”), we need to see that we can only respond appropriately to what thinking and technology give us when we allow thinking to open the technological to our reflection. That is, that what is called thinking in the technological framing is not the thinking that will allow us to understand the essence of this framing in itself. To understand this, the essence requires a different kind of thinking altogether.

But what is this framing and how are we to understand it? For Heidegger, framing is a manner of “revealing” or a bringing into “unconcealment” of that which was previously hidden. “To reveal” or to bring to “unconcealment” is, in Greek, aletheia, or “truth”; so the framing that rules in technology involves “truth” in some way, a “bringing to light”. The type of revealing or truth that rules in modern technology is the setting-upon and challenging forth that regulates and secures some thing as a resource and a disposable. Everywhere everything is ordered to stand by and to be immediately at hand so that it may be on call for further ordering or use. This is referred to as logistics. When we order some thing to stand by we determine some thing’s “value” for us. Those things that are not ordered to stand by are considered valueless, of no “value”. We can see the impact of this kind of thinking, viewing in the desire to “privatize” everything that exists that is presupposed to have some “value”.

Whatever is on call and stands by in the sense of resource no longer stands over against us as “object”. When human beings investigate, observe, ensnare nature as an area of their own conceiving (Kant), human beings are already claimed by a way of revealing truth that challenges them to approach nature as an object of research, until the object disappears into the objectlessness of resource. (M. Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, tr. W. Lovitt (New York: Harper & Row, 1977 herein after referred to as QT, p. 19). Framing is, thus, a way of being-in- the-world and enfolds what we understand by our cognition, our “consciousness”, and in so doing our understanding of what we call our “ways of knowing” or how we “grasp” and “appropriate” our world.

How is framing a way of being in the world, and as a way of being, how does it determine what we call “ethics”? While framing is a way of revealing, it is also a way of “concealing”; for example, it conceals the very nature of instrumentality that is our common understanding of what technology is. Our common collective assumption is an anthropological (human) and an instrumental definition of technology. These definitions reciprocate each other insofar as technology involves human activity (anthropological) and technology seems to facilitate the securing of various human needs and desires by providing the means (instrumental) to securing both which, in turn, involves all of human activity or praxis. The anthropological definition of technology requires an instrumental definition of technology since all human action seems to be “for-the-sake-of something” – it is teleologically oriented (purpose, goal-oriented).

The purpose or goal oriented root of the instrumental view of technology was, as we have seen in our writing on “Technology as a Way of Knowing”, (OT 1: Knowledge and Technology) found in the discussion of Aristotle’s four causes and in our discussion of the Greek word aition or “to occasion”. The four modes of occasioning (material, formal, final and efficient) are said to be “unifiedly ruled over by a bringing that brings what presences into appearance”, what we call “cognition”. “Occasioning” is what we refer to as “causation”. (Heidegger, QT, p. 10). Plato in his dialogue Symposium has Diotima say through Socrates: “Every occasion for whatever passes over and goes forward into presencing from that which is not presencing is poiesis, is bringing-forth.” (Symposium. 205b.) Poiesis is where something is brought forward, pro-duced, and becomes something that is present for us. Heidegger distinguishes the production (the bringing-forth) that belongs to nature (which is of itself i.e. a flower bursting forth in bloom, physis), and the production or bringing-forth that belongs to human beings which is the result of the occasioning in the four causes that we have spoken about. “…every bringing–forth is grounded in revealing…If we inquire, step by step, into what technology, represented as means, actually is, then we shall arrive at revealing. The possibility of all productive manufacturing lies in revealing.” (QT p. 12) This is the essence of many TOK essay titles where “the production of knowledge” is being considered. The knowledge that is being spoken about in the title is a “knowledge” that has been “revealed” through the “bringing-forth” and, thus, has a relationship with truth. It can be understood as the model or map that TOK offers as the guide to provide the direction on the path to what knowledge is: for a map to be constructed, the terrain must already have been explored in some fashion and details not considered significant “skipped over”.

Technology then is not simply a means to an end; it is a way of revealing the world we live in: the essence of technology is the realm of truth. As a way of revealing, it is a way of knowing. How human beings determine what truth is will, in turn, determine how they will live, their actions in the world i.e. their ethics. Ethics are not morals or laws. This understanding is a result of the influence of Christianity on the thinking of the Greeks. Ethics are the end products of human beings’ deliberations on what the essence of truth is. A reading of Aristotle’s The Ethics illustrates this; and it is this text which is the origin of the word ethics. CT 1: Perspectives (WOKs)

Heidegger claims that techne (making) has, from the Pre-Socratics until Plato, been connected with episteme (knowing): “Both words are names for knowing in the widest sense. They mean to be entirely at home in something, to understand and be expert in it. Such knowing provides an opening up. As an opening up it is a revealing.” (QT p. 13 ) Heidegger goes on to argue that “what is decisive in techne does not lie at all in making and manipulating nor in the using of means, but rather in the aforementioned revealing. It is as revealing, and not as manufacturing, that techne is a bringing–forth. (QT p. 19) “But man does not have control over revealing or unconcealment itself, in which at any given time the real shows itself or withdraws…Only to the extent that man for his part is already challenged to exploit the energies of nature can this ordering revealing happen. If man is challenged, ordered to do this, then does not man himself belong even more originally than nature within the resource?” (QT p. 19) Any human activity, and by this we can take Heidegger to mean any activity by humans at any time in history, does not occur within the vacuum of a false sense of autonomy but rather involves humans being “brought into the unconcealed. The unconcealment of the unconcealed has already come to pass whenever it calls man forth into the modes of revealing allotted to him.” (QT p. 19) It is not so much straightforward human progress which has led us to treat nature as a phenomenon to be investigated in this manner; rather there is something beyond us which seems to challenge us to reveal nature in this way:

Modern technology as an ordering revealing is, then, no merely human doing. Therefore we must take that challenging that sets upon man to order the real as resource in accordance with the way in which it shows itself. That challenging gathers man into ordering. This gathering concentrates man upon ordering the real as resource. (QT p. 19)

Framing is the hegemonic force at the heart of the essence of modern technology (that which “spreads like a fungus”, as Hannah Arendt would say in her discussion on evil) which is itself nothing technological; evil itself is not a construct of the human mind but, as Plato would say, is the deprivation of the good. It is the deficiency, the deprivation, of the truth of things, the deficiency of knowledge, the lack of or dimming of the light. Framing is the manner in which the real, and our understanding of the real, is revealed by us such that modern human activity and behaviour is something which resembles what we now understand as modern technology. Technology is our way of being in the world. Techne, which we understood as a primordial or original kind of revealing from our brief discussion of the passages from Aristotle regarding “occasioning” which Heidegger cites earlier, has now come to be shown as the essence of modern technology, and has come to be shown to be the kind of revealing that modern technology ordains; however, it is a very particular kind of revealing and is not a revealing as poiesis:

Framing is the hegemonic force at the heart of the essence of modern technology (that which “spreads like a fungus”, as Hannah Arendt would say in her discussion on evil) which is itself nothing technological; evil itself is not a construct of the human mind but, as Plato would say, is the deprivation of the good. It is the deficiency, the deprivation, of the truth of things, the deficiency of knowledge, the lack of or dimming of the light. Framing is the manner in which the real, and our understanding of the real, is revealed by us such that modern human activity and behaviour is something which resembles what we now understand as modern technology. Technology is our way of being in the world. Techne, which we understood as a primordial or original kind of revealing from our brief discussion of the passages from Aristotle regarding “occasioning” which Heidegger cites earlier, has now come to be shown as the essence of modern technology, and has come to be shown to be the kind of revealing that modern technology ordains; however, it is a very particular kind of revealing and is not a revealing as poiesis:

In Framing, that unconcealment comes to pass in conformity with which the work of modern technology reveals the real as resource. This work is therefore neither only a human activity nor a mere means within such activity. The merely instrumental, merely anthropological definition of technology is therefore in principle untenable. (QT p. 21)

The revealing at work from out of Framing does not happen “decisively” through humans, though it does happen exclusively through us. We are not in a position where we can bend the real to our vision or will, try as we might to overcome and conquer necessity and chance or to choose a world of “alternative facts” in which we are consumed by “unreality”. In trying to take up a position with respect to Framing, we can only assume any comportment to framing subsequently, that is, after we have already articulated its manner of revealing the real. Since we have been granted by Being that we are always and everywhere the beings who reveal as human beings, our attempts to grasp that which allows us to reveal can only ever be subsequent to its actual appearance as the precursor to our activities (ethics) or thoughts. The revealing as Framing is a priori.

But, as Heidegger states: “Never too late comes the question as to whether we actually experience ourselves as the ones whose activities everywhere, public and private, are challenged forth by Framing.”(QT p. 24-25) The essence of modern technology then pushes us in a direction, or as Heidegger puts it “starts man upon the way”, with a view to constraining us to reveal the real everywhere as resource to be at human disposal. To be so affected is to be delivered or “sent” by Framing. But in the process of being delivered over in this way, we are gathered up into effecting a unified and unidirectional way of being-in-the-world; we are drawn together into a course of action, we are made to cohere, as what we are, as beings that reveal in this way. Heidegger calls this “sending-that gathers” destining. In this destining, both East and West come together in their mode of being and in their mode of revealing in the world. This coming together has sometimes been referred to as “globalization”.

Framing, so construed then, is “an ordaining of destining, as is every way of revealing.”(QT p. 25) Even poiesis is an ordinance of destining when we understand things in this manner. Framing ordains the manner in which we are ‘sent’ such that we tend to reveal the real in a specific, pre-determined, predestined way (the mathematical, calculable) through the mathematical projection. That we reveal and are destined to reveal in a specific way has always been the case for humanity throughout history, but the destining we are subject to, so Heidegger argues, “is never a fate that compels.” (QT p. 25)

The reason that we are not utterly given over to destining as an ineluctable fate relates to the fact that, as the beings who are called forth in this way and, as such, are capable of listening to and hearing this summons, we are more than simply beings who are “constrained to obey” but are beings who can hearken. It is through the “hearing” that we can attain “freedom” within the technological. “The essence of freedom is originally not connected with the will or even with the causality of human willing.” (QT p. 25) When speaking of freedom, Heidegger insists that it is freedom understood as that which “governs the open in the sense of the cleared and lighted up, i.e., of the revealed. It is to the happening of revealing, i.e., of truth, that freedom stands in the closest and most intimate kinship.” (QT p. 25) It is in this “open” clearing that the ethical is possible because it is where action is possible. It is in this open clearing that the tools and instruments of technology are brought forth, “produced”, in their being.

For Heidegger this revealing through technology, however, fundamentally and at the same time belongs within a concealing and harbouring. Aletheia, as “unconcealment”, “revealing”, “truth”, is the dis-closure or un-concealing. Privation, the “a-“ in a-letheia, involves the privation of the opposite state, “lethe”, which is “oblivion”, “forgetfulness”, “hiddenness”. The state of being closed/covered over or concealed becomes un-covered, dis-closed, unconcealed. Similarly, what frees is itself concealed already and is perpetually concealing itself. If something is freed, it had to come from the opposite state which preceded that event, namely, being confined or unfree. The happening of revealing occurs from out of the open “goes into the open, and brings into the open.” (QT p. 25)

But freedom, as that which governs the open, has nothing to do with “unfettered arbitrariness” or the “constraint of mere laws”. Rather, freedom is something that in concealing sheds light and opens up so that light can penetrate through to what was concealed, “in whose clearing there shimmers that veil that covers what comes to presence of all truth and lets the veil appear as what veils.” (QT p. 25) Freedom is our allowing the light to be as light and as such “Freedom is the realm of the destining that at any given time starts revealing upon its way.” (QT p. 25) For Heidegger, any other conception of freedom is an illusion which captures us within the confines of the Framing which holds sway and which causes us to turn from the light as light. This freedom allows us to recognize that “we are not our own” in our actions and it assists us in our recognition that Love is the proper response to Being.

The alternative that Heidegger sees for modern human being is “…that man might be admitted more and sooner and ever more primally to the essence of that which is unconcealed and to its unconcealment, in order that he might experience as his essence his needed belonging to revealing” (QT p. 26). But, “The destining of revealing is as such, in every one of its modes…. danger.” (QT p. 26) What is the danger of which Heidegger speaks? Is it that the technological has led us to the possibility of nuclear annihilation or climate catastrophe? No. When the unconcealed is no longer revealed for us as an object or objects but rather is revealed “exclusively as standing reserve” or “disposables”, those who allow the real to be so revealed become nothing more than the orderers and organizers of the resource. We are, at that stage, on “the very brink of a precipitous fall” as we are now in a position such that we ourselves have come to be “taken as standing reserve.” (QT p. 26) Cybernetics, the unlimited mastery of human beings by other human beings, is the ineluctable and inevitable conclusion to this “precipitous fall” for it is within cybernetics that human beings are seen, ultimately, as merely disposables or resources to be manipulated and used, and this “use” and manipulation is the ethical. The experience of the Covid-19 pandemic should illuminate to us the clarity of this point: human beings in their denial of truth become less “humane”. This denial of truth is the great danger to the essence of human being and to the actions that human beings take.

We fail to understand what our essential situation is, that is our ethical situation, if we fail to attune ourselves to the way in which we are determined in advance by Framing and how this essentially dictates the manner we comport ourselves toward reality and towards others within that reality. Framing in its revealing everything as ordered and calculable excludes all the other possibilities available to us with respect to how the real can be revealed. Framing binds us so that there is nothing other than a challenging, calculating view of the world and this view is one which endures at the expense of all others; it is the viewing which determines our values of the things that are. Framing ultimately blocks the advent of ‘truth’, again truth as the revealing or unconcealment, which is the ultimate danger. Technology itself is not what threatens us but rather “the mystery of its essence.” (QT p. 28) Framing threatens to separate us completely from where originary truth happens, leaving us abandoned and forlorn on an Earth where contact with our essence as human beings is impossible and where any possibility of true human freedom is denied.

For Heidegger, we are not completely lost to Framing. For him, within Framing is the “saving power also”. “To save,” for Heidegger means to reunite something with its essence and in that sense to re-admit something into that for which it is fitted i.e. its justice. In discussing Framing’s danger, Heidegger looks to finding its essence. He, like Socrates, finds its essence to be related to human being in communities and he speaks of the site of a village (we might even say “the global village”) where the “city hall” is the place where the community gathers or the “they-Self”:

that share in revealing which the coming-to-pass of revealing needs. As the one so needed and used, man is given to belong to the coming-to-pass of truth. The granting that sends in one way or another into revealing is as such the saving power. For the saving power lets man see and enter into the highest dignity of his essence. This dignity lies in keeping watch over the unconcealment – and with it, from the first, the concealment – of all coming to presence on this earth. (QT, p. 32)

How are we to counter the “unholy blindness” (QT p. 33) that presents itself to us in the essence of Framing? “Here and now and in little things, that we may foster the saving power in its increase. This includes holding before our eyes the extreme danger.” (QT p. 33)

What is the “extreme danger”? The extreme danger is that which threatens all revealing, “threatens it with the possibility that all revealing will be consumed in ordering and that everything will present itself only in the unconcealedness of resource. Human activity can never directly counter this danger. Human achievement alone can never banish it. But human reflection can ponder the fact that all saving power must be of a higher essence than what is endangered, though at the same time kindred to it.” (QT p. 33)

Heidegger goes on to find that it is in the revealing that is to be found in art that is the manner that human beings may hope to find the “saving power” from the manner of revealing that lies in the essence of Framing. In this way, Heidegger turns from Socrates who in his thinking did not find in art the “saving power” or the way to the revealing of the good, beauty and truth, and Heidegger turns, instead, to Nietzsche.

Ethics and Society: Finding The Link between Duty and Evil

If Framing as a way of being in the world is to be overcome and transcended, then it is through and within thinking that this overcoming and transcendence will take place. By “overcoming” is not meant conquering; Heidegger makes it quite clear that we cannot conquer “Framing”. But if Framing is the essence of modern human being in the world, and if this essence is part of the fallenness of human being, how will it be possible to overcome it? We do not wish to use the words “optimism” and “pessimism” here; as modes of Being-in, these words are products of the technological world-view. (“Optimism” and “pessimism” as world-views are first found in the writings of Spinoza. These later become taken up by Leibniz in his securing of the principles of reason.)

For the existentialists (Heidegger, although this term is used guardedly with reference to him since he rejected the term to describe his philosophy), the German word verfallen carries connotations of “lapsing” or “deterioration”, the “lethe” of oblivion and forgetfulness as distinct from the “alethe” of disclosure, unconcealment, and truth. One “falls into” bad habits, for example. Despite these connotations, Heidegger insists that Verfallen is not a term of moral disapproval and has nothing to do with the Christian fall from grace (It is interesting to note, and cannot be forgotten, that of all the great German philosophers, Heidegger is the only one that was from a Roman Catholic and not from a Protestant background.) “Human Being has first of all always already fallen away from itself as authentic ability-to-be-itself and fallen into the “world” (Sein und Zeit (15th ed. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1979) Being and Time, tr. J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson (Oxford: Blackwell, 1962) referred to as BT throughout. BT, 175). The fall is an Angst-driven ‘flight of Human Being from itself as authentic ability-to-be-itself (BT, 184). Heidegger gives three accounts of what Human Being has fallen into and, implicitly, of what it has fallen away from (BT, 175):

- Verfallen means: ‘Human Being is firstly and mostly alongside the “world” of its concern’ (cf. BT, 250).

- ‘This absorption in . . . mostly has the character of being lost in the publicness of the They’.

- “Fallenness into the “world” means absorption in being-with-one-another, as far as this is guided by ‘idle talk, curiosity and ambiguity’.

For Heidegger, the Fallenness suggested in Account 1 is that in virtue of falling Human Being attends to its present concerns. It is shopping at the shopping mall, busy at the computer. In what sense has Human Being fallen away from its ‘authentic ability-to-be-itself’? It does not have in view its whole life from birth to death. It interprets itself in terms of the world into which it falls, ‘by its reflected light’ (BT, 21; perhaps Plato’s allegory of the Cave should be kept in mind here as well as the understanding of Framing); it thinks of itself in terms of its current preoccupations. It is not making a momentous decision about the overall direction of its life. It is not suspended in Angst, aware only of its bare self in a bare world. We could, of course, take issue with Heidegger here regarding the “ethical” nature of human beings’ fallenness, but that will not be done here (nor are we capable of doing it).

In Account 2, Human Being’s present concern is mostly a publicly recognized and approved activity, even if done in private. Heidegger implies that Human Being is doing what it does only because it is what THEY recommend. Within the Framing mode of the technological, the separation of public and private spheres becomes blurred and, perhaps, there is in fact no separation. The they-Self rules and takes predominance. We might think about this with regard to our social networks and virtual world activities as well as those activities which occur in our research.

In Account 3, what I do may be tacitly guided by others (the They, corporations, the State, ideologies). The self becomes ‘absorbed’ in togetherness and in ‘idle talk’, curiosity and ambiguity. The essential feature of Human Being here is in the way its concern is for the present and for the public recognition of its activities (Hegel). It needs to be remembered that all of these activities are conducted within the Framing that is the technological.

Human Being’s falling impairs its ability to think: as well as falling into its world, Human Being also ‘falls prey to its more or less explicitly grasped tradition (Framing) or our ‘shared knowledge’, such as we are concerned with in CT 1. This “falling into” deprives it of its own guidance, its questioning and its choosing. That applies not least to the understanding rooted in Human Being’s very own being, to ontological understanding and its capacity to develop it’ (BT, 21).

Concern with the present, which is central to falling in all three accounts, obstructs a critical inspection and introspection of what is handed down from the past, since that would require an explicit examination of the tradition in its foundations and development (what we have been attempting to do here in these writings about TOK by understanding Framing as the essence of technology and how it impacts our understanding of our traditions and our histories). This is the sense in which Human Being, engrossed in its present concerns, is ‘lost in the publicness of the They’: it mostly continues to act and think in traditional ways or in the mannerisms of Framing, but its actions are characterized by “rootlessness”. Busy businessmen and women do business and network in the same old ways; consumers busy themselves with ‘getting and spending’; students attempt to make their ‘thinking visible’ within ‘design cycles’ of representational thinking which are themselves within the same old ontology of Framing which does not question its own origins. For Heidegger, ‘Being abandons beings, leaves them to themselves and so lets them become objects of machination’.

To understand “machination” is to remember that technology is not primarily a ‘making’ but the ‘knowing’ that guides our dealings, our making, with and within the world about us, our views of nature and other human beings. Technology is a way of ‘revealing’ that precedes the making: ‘That there is such a thing as e.g. a diesel engine has its decisive, ultimate ground in the fact that the categories of a “nature” utilizable by machine technology were once specifically thought and thought through by philosophers’. Heidegger retrieves its link with making and interprets it as ‘makership, machination, productivity’, the tendency to value only what we have made and what we can make into something, including human beings (empowerment). “Machination” also includes our understanding of “producing” knowledge.