Take but degree away, untune that string,

And, hark, what discord follows: each thing meets

In mere oppugnancy; the bounded waters

Should lift their bosoms higher than the shores,

And make a sop of all this solid globe;

Strength should be lord of imbecility, And the rude son should strike his father dead;

Force should be right, or rather, right and wrong

(Between whose endless jar, justice resides)

Should lose their names, and so should justice too.

Then every thing includes itself in power,

Power into will, will into appetite,

And appetite, an universal wolf,

(So doubly seconded with will and power),

Must make perforce an universal prey,

And last, eat up himself. –Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida Act 1 sc. iii

If we look at the area of knowledge that is called The Human Sciences, we note that an answer to the ontological question “What are human beings?” is prior to the political question, “How have human beings determined their arrangements for living in communities?”. The answer to the “what” determines the various interpretations of the “how”. That human beings are beings in bodies has created the dualism which informs many of the conflicts that focus on the answers to the “how”. In answering the ontological question, the primacy of reason or emotion (passion, will, appetite), sense perception and/or intuition come to the fore. We have the conflict between “materialism” and “idealism”, the conflict between “matter” and how that matter is understood.

Human beings as they are in nature and by nature, human being as an individual, and human beings in society, “civil society”, or a society of “laws” are all themes that need to be considered when discussing The Human Sciences. With regard to the nature of the laws, the issues of positive law (laws made by human beings) and natural law (laws that are outside of human beings and are, thus, permanent), and how the understanding of Nature changed with the arrival of modern Natural Science through Newton and its impact on our understanding of “natural law” and “positive law”, are things for consideration if one wishes to understand where our interpretations of beings and things comes from and in so doing come to some understanding of ourselves. (CT 1, CT 2, CT 3)

Nowadays, human beings are viewed as a species. A species is a distinct group of animals or plants that have common characteristics and can breed with each other. In Middle English, species meant “a classification in logic,” borrowed from the Latin word meaning “kind or appearance,” from the root of specere, “to see.” Darwin’s great work, which has come to determine how we view or see human being in the present, is called The Origin of Species. The determination of species is arrived at through a taxonomy. As Wikipedia tells us: “Taxonomy is the practice and science of classification. The word is also used as a count noun: a taxonomy, or taxonomic scheme, is a particular method of classification. The word finds its roots in the Greek language τάξις, taxis (meaning ‘order’, ‘arrangement’) and νόμος, nomos (‘law’ or ‘science’, ‘convention’). Originally (?), taxonomy referred only to the classification of organisms or a particular classification of organisms. In a wider, more general sense, it may refer to a classification of things or concepts, as well as to the principles underlying such a classification.” I have placed a question mark behind “originally” as behind the understanding of this word is the “wider, more general sense” that is the origin of the word “taxonomy”, and this is what is first in order. As we have attempted to demonstrate in these writings, the principle of reason is the ground of the “ordering arrangements” (logic) that we use to “see” and frame the world around us, and this viewing and framing of the world is a part of that whole that we have called “technology”.

In Part II, we shall continue to examine the historical background behind the understanding of what are called The Human Sciences today by providing precis or prefaces of the thinking of Rousseau, Kant, Hegel and Marx. In Part I, we examined primarily English-speaking political philosophers who found the grounds of their thinking in the Italian political philosopher Machiavelli. In Part II we shall examine the Continental political philosophers (for lack of a better term) who were critical of that thinking. Our purpose is to arrive at an understanding of the assertion that “Communism and capitalism are predicates of the subject technology” and in doing so arrive at a better understanding of what we mean by the being of human beings in communities and societies.

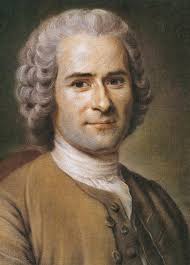

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)

English-speaking teachers of philosophy have had a great deal of difficulty understanding and coming to terms with the French philosopher, Jean Jacques Rousseau. To many, Rousseau has been seen as an unsystematic poet, quite incapable of the sustained, disciplined thought necessary to the true philosopher. Such accounts can be found from Jeremy Bentham to Karl Popper. Bertrand Russell in his History of Western Philosophy goes so far as to say that Rousseau should not be called a philosopher; he is a self-indulgent poet. His thought is filled with contradictions of such an obvious nature that even a high school student of average ability could discover them. Russell concludes that Rousseau’s “insights” culminate politically in National Socialism, and so on, etc. However, when one reads Russell’s precis of the chief writings of Rousseau in his text, one cannot recognize Rousseau’s originals.

That such interpretations of Rousseau have been sustained in English-speaking philosophy is curious since modern English thought is anti-theological in its intent and Rousseau is an atheist. It is in Rousseau that we find the old traditions destroyed by his saying that reason is acquired by human beings in a way that can be explained without teleology i.e. without an end or purpose. Our lack of attention to the thought of Rousseau, for those of us who are English-speaking, has limited our self-understanding and our self-knowledge (CT 1, CT 2, CT 3).

Perhaps the cause of the lack of attention to Rousseau in the English-speaking world may be attributed to the long ascendancy of the English-speaking peoples, from the battle of Waterloo to the present USA, under the rule of various species of bourgeois. This word is almost a Rousseauian invention. When the ruling classes believe their shared conceptions of political right to be self-evident and they are not seriously questioned at home, and when they are expanding their empires around the world, such a bias is hard to overcome. The IB program, for instance, is but one flowering of this bourgeois vision. As the cliche goes, the victors get to write the history and so to form the opinions that determine how they understand themselves.

When we speak of the need for self-preservation today, we are immediately reminded of Darwin, but Darwin is not possible without first the thinking of Rousseau. It is in the thinking of Rousseau that we find the need for the history of the human species. Rousseau concluded that we cannot find the essence of what human being is if we merely study primitive societies i.e. anthropology, for we are still looking at human beings within societies and we must look for even more primordial beginnings.

Rousseau begins by divesting human beings’ essence from reason since reason requires speech or language and language is only necessary within communities. What takes the place of reason, for Rousseau, is “freedom” of the will to make choices, and this liberty is evidence of the spirituality of the human soul: human being is aware of its own power as “potentiality”, as “possibility”. The human being is also aware of his “malleability” and “perfectibility” through the development of his faculties through education, his “shared knowledge”. “Natural man” has no definable essence at all; he is the “free animal” with no ends but only possibilities. This nature of human being leads him away from his original happiness in “nature” to the misery of civil life; but it also renders human being capable of mastering himself and nature.

With communal interests arises a sense of morality, a sense of obligations. For Rousseau, the foundation of “private property”, the cultivation of the soil in agricultural activities, is that which brings the greatest evil to humanity. The farmer must think to the future, and the protection of his crops causes him to seek power. It is with the foundation of private property that we find the origin of inequality. There is a state of war between the “haves” and the “have nots”, those who have property and those who do not, and this state of war prompts the need for the “social contract”. Hobbes is right when he says that the human beings who are constrained to found civil society are hostile to one another and inflicted with infinite desires. He is wrong only in asserting that this is the nature of human being, according to Rousseau. Locke is right when he asserts that the purpose of civil society is to protect property. He also is wrong in asserting that property is natural to human being and that inequalities are stabilized by civil society’s conforming to real standards of justice. For Rousseau, human beings are naturally free and civilized society takes this freedom away; human beings become dependent on law and the law is made in favour of the wealthy and the powerful.

For Rousseau, the political question is the moral question. He begins his Social Contract with the famous words: “Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains…How did this change come to pass? I do not know. What can make it legitimate? I believe I can resolve this question.” Contrary to the Greeks (Plato and Aristotle), for Rousseau civil society is not a “natural” phenomenon because nature is too base, too low to bring forth such a phenomenon. Socrates asserted that the nature of man was “to live well in communities and think about the whole”. Such is not the case for Rousseau. Nature dictates only self-interest; nature is rejected as a standard for civil society. The passions require a stringent morality for civil society to be successful. Rousseau sees that a morality based on the calculation of self-interest would only lead to tyranny or anarchy as Plato had indicated in his Republic. Human beings must create their own morality. The resolution of the problem of the relation between individual freedom or between self-interest and duty and bondage to society is Rousseau’s effort in the Social Contract.

The establishment of civil society is identical with the making of morality or the binding contractual commitments to others. What this illustrates is that human beings’ will is not limited by nature. Human being, as the makers of their own morality and of civil society, is the fulfillment of their definition as the free, undetermined being. Human being is the being that wills, and the capacity to do what they will is the essence of freedom or what human beings are. This freedom is independent of and opposed to morality, yet it is the sole source of that morality. There is no eternal reason which can and should control our actions. Reason and reasons are the essence of freedom. Each person has their own judgements based on their personal knowledge and experience and their actions are based on their particular wills and appetites. The political solution, for Rousseau, is that every person gives themselves entirely to the community with all their rights and property. Law is the product of this “general will”, and these laws apply to all.

In Rousseau, both nature and revealed religion are cast aside as sources for the moral law. Human beings in their freedom establish the laws and, thus, morality. The “amiable beast” of nature becomes a moral, ethical being and his “private will” is given over to the “general will” that now becomes “sovereign” through the “social contract”. Education and punishment constrain the individual to act according to the “general will” from which true human dignity and nobility arises. Individuals must be citizens in the classical sense and this requires a very severe, self-imposed morality. Rousseau disagrees with democracy as we traditionally understand it because, as Plato indicated, it was driven by an anarchy of self-interests. The education to virtue is not the end of society but, paradoxically, the means to freedom.

How technology (understood as Reason and the discovery of reasons) influenced or determined Rousseau’s political philosophy is in the manner that he attempted to combine the theory of political philosophy with the art of the classical political philosophy of Aristotle in the actions of the statesman/legislator i.e. the lawmaker or, in Rousseau’s case, “ordinary” human beings. The state is a product of the wills of these “legislators”, not prior to them. Good governments arising from these wills were very “iffy” and so it was necessary to do what one could to overcome this chanciness through institutions. The separation of the legislative and executive branches, the lawmakers and those who executed those laws, was also a requirement and this prefigures the separation of the state and society that is so important for us today. This separation is in direct contrast with the classical thinkers who viewed the society as being determined by the form of government i.e. the regime determines the character of the society and its members.

Rousseau never envisioned that a common use of the world’s resources was feasible. As with civil society itself, private property and civil society are bound together. Both civil society and private property are not ‘natural’ and are always a cause of inequality. Private property is the root of power in civil society and will determine the laws within it. Money has a great deal to do with the capacity to remove impediments to freedom and allow access to the realm of the arts and sciences where this freedom is empowered. The arts and sciences promote inequality rather than allay it. Society protects the rich, and the poor have much less to lose and perhaps much to gain in the destruction of the established order and its laws. Private property becomes a difficult question after the words “legitimate civil society”. Marx would resolve this question with the abolition of private property.

The difficulty in Rousseau’s thinking regards the nature of human being. The virtue, the living according to principle, that aims at human perfection and is demanded by civil society is antithetical to the animal and emotional nature of human beings. What was essentially good in itself for human beings according to the ancients is not so for Rousseau. Rousseau makes a distinction between the moral human being and the good human being. The moral human being acts from a sense of duty and is a trustworthy citizen. The good human being is one who follows his natural instincts, that first primordial nature uncorrupted by vanity. For Rousseau, civil society does not satisfy much of what is deepest in human beings. He did not believe that human beings could become entirely social.

So why should we read Rousseau? If we wish to understand ourselves as human beings, we need to understand how the presence of the concept of “history” arises on the English-speaking stage. By “history” is meant that process in which human beings are believed, by some, to have acquired their abilities. History is not a form of study but a realm and a way of being-in-the-world, one possible realm and one possible way. The understanding of history requires a “philosophy of history”.

History took its place upon the public stage in the English-speaking world through Darwin, and Darwin is central for the English because he dealt with the natural sciences. English-speakers do not teach Darwin as theory but as fact. What was important for Darwin was not evolution as natural selection, but how evolution took place. In 1863 he wrote: “Personally, of course, I care much about Natural Selection; but that seems to me utterly unimportant compared to the question of Creation or Modification.” (Life and Letters, Vol. 2, p. 371). Modification is, of course, the central question and modification in this sense is a synonym for “history”. How does “modification” relate to Rousseau?

Rousseau was the great critic of Locke and his contractualism. Locke’s contractualism is ahistorical and what has occurred in the English-speaking world is a continuous attempt to hold together an ahistorical account of reason along with an historical account of nature. The attempts are made to maintain the contractualism of human beings living in societies freed from any ontological statements about what human beings are. Darwin knew that this was not possible. The debate between Creationism and Modification is an ontological one, for in it human beings are defined. You cannot hope to combine successfully an ahistorical political philosophy within a natural science which, at its core, is historical.

With the idea of modification as history, we are led back to Rousseau for it is Rousseau who said that what we are as human beings is not given to us by nature but is the result of what human beings were forced to do to overcome chance or to change nature, “improve” it, and make it useful for our ends; technology is the determiner of what human beings are and will be by “modification”. Human beings have become what they are and are becoming what they will be. We are the free, undetermined animal who can be understood by a science which is not teleological. We can be understood “historically”. This is Rousseau’s great achievement.

Suggested Readings

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts. https://www.stmarys-ca.edu/sites/default/files/attachments/files/arts.pdf

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men. http://faculty.wiu.edu/M-Cole/Rousseau.pdf

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Social Contract Bks I and II. https://www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/rousseau1762.pdf

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

The philosopher Immanuel Kant is credited with achieving a “Copernican revolution” in the area of metaphysics. Just as Copernicus put the sun at the centre of our “solar system”, Kant puts human beings at the centre of their worlds and grounds what we have come to call “humanism”. Kant’s achievements are immense, and it is quite impertinent on my part to attempt to summarize them in a short precis such as this one.

Kant attempts to resolve the conflict between science and morality, the tension that exists between the physics of Newton and its determinism and the moral conscience that was expressed by Rousseau in his notion of freedom of the will. To do so, Kant distinguished between the “phenomenon” or the beings and things (objects) as understood by science, and the “noumena” which were the objects of morality. In order to understand what Kant meant by these terms, we must say a few words about Kant’s “transcendental” methodology. In doing so we ask the question: how are the “phenomenon” and “noumena” possible?

In the history of thinking, things are experienced through many different concepts and names and are constantly under scrutiny with respect to the “how” of their being, of what they are and how they are. Their “how” is never posited first by human cognition. Our experience of Life is that it gives itself to us as a temporal space for all human activities, what we do as human beings, including our stance towards the beings that are within it.

In his Critique of Pure Reason, Kant elaborates how rational cognition, the rendering of sufficient reasons for what can and cannot appear to human beings as a being, an object, is to be decided in the judgement of the rendering of sufficient reasons. Kant demonstrates that what we understand as the “objectness of experienceable beings” is based on the principle of sufficient reason. This “objectness of objects” is prior to our cognition of them as such and rests in the subjectivity of Reason, the ego cogito of Descartes. The method that surpasses objects and comes to determine them is called by Kant “transcendental”.

The “transcendental method” is not a procedure that moves around external to objects. The method of rendering sufficient reasons is “transcendental”, not “transcendent”, because for Kant what is “transcendent” is that which lies beyond the limits of human experience and is unknowable. The “transcendent” surpasses objects along with their objectness without rendering sufficient reasons for their possibility of being founded or grounded. To use our common term, the “transcendent” and its conception is “subjective”. Something that is “subjective” remains to be grounded; it remains within the realm of “opinion”. According to Kant, a cognition is “transcendent” that pretends to know objects that are inaccessible to experience. In contradistinction to this, the transcendental method has a view to the sufficient ground of the objects of experience, the reasons behind experience, and thereby the grounds of experience itself. It can answer the what, the how, and the why questions for it renders reasons. The transcendental method moves with the grounds (Reason) that found and ground the objects of experience in their possibilities.

Because the transcendental method remains within the circle of sufficient reason for the possibility of experience, the essence of experience, the transcendental method is immanent. It sets the boundaries for the authority of the “transcendent”. The transcendental method covers all the immanence, the inwardness of subjectivity i.e. it traverses that cognition or “consciousness” wherein the objects of representation reside in their sufficient reasons i.e. their objectness, their being as beings/things. Kant asserts: “The mind makes the object”.

It was Hume’s skepticism that awakened Kant from his “dogmatic slumber”. Hume maintained that our fundamental notions of necessity and causality are validated by experience and convenience, not by reason. Kant demanded that the principles that support our understanding, especially causation, be better grounded than upon mere experience lest their necessity and universality become unintelligible and the possibility of science, particularly mathematical physics, be lost. He does so through the distinction of analytic and synthetic judgements.

An analytic judgement is, in Kant’s example, “All bodies are extended”. In thinking of a body we can’t help but also think of something extended in space, something that is part of what is meant by “body.” The subject (body) implies the predicate (extension). The validity of analytic judgements is independent of experience; such judgements are a priori. He contrasted this with “All bodies are heavy,” where the predicate (“are heavy”) “is something entirely different from that which I think in the mere concept of body in general”, and we must put together, or “synthesize,” the different concepts, body and heavy. The predicate adds something to the subject. Judgements based on experience are necessarily synthetic, and they are a posteriori meaning they follow after experience. This is the position of Hume and of empiricism. But experience itself is not possible if there are not synthetic judgements a priori, judgements that are incapable of being validated by experience. “Synthesis” is the rational gathering of the categories that make up what we mean by the word “object”.

For example, all experience presupposes the principle of causality. Hume had failed to see that the principle of causality is not derived from experience but is the presupposition for all possible experience. The principle of causality is only one aspect of the principle of reason itself (“nothing is without reason (a reason”) and the whole system of categories and the forms of pure intuition (space and time) supply the framework that renders possible the science of nature. This framework is the mathematical calculus that make objects possible. We have called this framework and its system of ordering and gathering “technology” in these writings. Science of nature, of the “phenomenal world”, is not a contemplation of a reality outside ourselves but is the laying down of laws to nature by ourselves. It is a summonsing of nature to give us its reasons and it is a willing on the part of human beings. Because it is an act of will and, thus, a product of what Kant calls “practical reason”, Kant is able to fuse the theory of the phenomenal world with the morality of the noumenal world. Our modern emphasis on action instead of contemplation finds its source here in Kant’s autonomy of the human will as “subject”. Morality is the only “fact” of reason, as Kant had said.

Kant’s understanding and restructuring of “subjectivism” rests in his transcendental methodology in that in the determination of the objectness of objects, the method itself belongs to “objectness”: “The mind makes the object”; but the mind, too, can be known as an object as is shown in the area of psychology. Cognition renders sufficient reasons when it brings forward and securely establishes the objectness of objects and thereby belongs itself to objectness, that is, to the being of experienceable things. The transcendental method belongs to and responds to the claim of the principle of reason, and through it the human being experiences their freedom. Our experience of the world is one of being amid objects and all other determinations of the being of these objects is precluded. What makes the being of objects possible is Reason itself. This is what we mean by the “personal knowledge” of experience for which sufficient reasons must be rendered in order for it to be considered “knowledge”. Without the sufficient reasons supplied for our “experience”, we would be utterly unsure if it was not madness.

When we say that the objectivity of objects is based upon “subjectivity” we mean that this objectivity is not confined to a single person as something fortuitous to their individuality, situation, and discretion. Subjectivity is “the lawfulness of reasons which provide the possibility of an object”. Subjectivity does not mean “subjectivism” but rather is the presence of the claim of the principle of reason which has as its consequence the inauguration of The Human Sciences and, further, the Information Age in which the particularity, separation and validity of the individual disappears in favour of a total uniformity in a similar manner to how the uniformity of matter in The Natural Sciences is conceived. This unleashing of the principle of reason demands the universal and total reckoning up of everything as something calculable. Without such reckoning up, our computers and hand phones would be quite useless to us, but this reckoning is also a definition of what we are as human beings. We are the reckoners and the calculators of our own “interests”.

That which is most difficult to grasp because it is closest to us is ourselves (to paraphrase Aristotle). Kant sets out to demonstrate how the things and beings of the world are objects for us. Our cognition’s reply to the objects that we experience is to give these objects their full determination as objects. The “transcendental method” does not occupy itself with the objects themselves but with the manner in which the objectness of objects and our knowledge of them is a priori. The “transcendental method” is how the objects can be objects for us. Whatever comes to presence in what is over-against us (ob-ject, jacio-“the thrown against”) and what comes to presence in objectness is that the status of an object is determined by cognition on the basis of the a priori conditions for the possibility of cognition. It is by referring back to the subject that cognition, so determined by Kant, goes about rendering the sufficient reasons for the presencing of what comes to presence as object. Through rendering the sufficient reasons, this cognition receives the unique character that determines the relationships that modern human beings take towards the world and this makes what we call the technological possible.

Ratio, which comes from the Latin reor, means “to take something for something, to put something in its place, to put something in order for something else”. “To reckon” or “count on” something means to expect it and to see it as something upon which one can build. The original sense of “reckoning” does not relate to number. “Calculus” is a playing piece in the ancient game of draughts used to “count things up”. “Calculation” is a reckoning as deliberation: one thing is placed over against another so as to be compared and evaluated. “Reckoning” with numbers is a “reckoning on” something; that which is thus reckoned is produced for cognition and brought into the open, into presence. Through such reckoning, something comes about; thus we have what is understood as “cause and effect” which we believe we can count on, and this belongs in the realm of ratio. When we reckon, we represent what must be held in view, that with which and in terms of which we reckon with some matter. In this reckoning, that which is is put in place and is taken up as some thing and is put in order so that something else may be built upon it. This is what happens when we use algorithms, for instance, whether that algorithm is as simple as a recipe for scones or the program for a super-computer. It is how we measure “intelligence” in our IQ tests and what we speak of when we are speaking of “artificial intelligence”. It is also what we mean when we speak of our art as “aesthetics”; it is the means by which we understand the work of art. The work must first be turned into an object so that it can be handled and dealt with.

Kant’s separation of the realm of freedom from the realm of nature also grounded what we call “the fact/value” distinction, a distinction which the practitioners of the Human Sciences claim is necessary for their efforts to be regarded as “science”. While such a distinction is made in the philosophy of David Hume, it is not grounded there. It is Kant who does so. The distinction rests on the understanding and separation of the world as “phenomenal”, the world of empiricism and science, from that world of “noumenal” things, those principles of reason which human beings give to nature to make “objectivity” possible. Kant grounds Descartes’ ego cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”) and in this grounding defines what human beings are (“I am this…thinking”).

This long, difficult preamble to Kant is necessary because in it Kant defines what human beings are and, thus, what The Human Sciences are going to be if they are to be “sciences”. There are few references to societies and politics in his three Critiques: The Critique of Pure Reason, The Critique of Practical Reason, The Critique of Judgement. We will examine Kant’s moral philosophy and his philosophy of history to illustrate his revolutionary vision of what modernity is and what we mean when we speak of The Human Sciences. This revolution of human being-in-the-world occurs through Kant’s own metaphysics which are outlined above (the phenomenon), and in his dealings with the ideas of modern natural right which one finds in the writings of Hobbes, Locke, and especially Rousseau. For Kant, peace depends on law and law depends on reason, and there is a drive in the nature of things towards a free, rational, peaceable state, that faith which is best exhibited in what we call the age of progress.

In Kant’s system, the world of the noumena is the world which is opened up by morality. In this world, Reason attains perfect freedom from the limiting effect of the realm of natural things or the Necessary, the realm of necessity where all that is is turned into objects because the object itself determines the best method to be used to determine it. Reason is the realm of freedom from the knowing, the doing, the making and the acquiring that is the world of natural things. In this way, Kant separates the empirical, the world of the sciences, from the noumenal world of morality and in so doing separates happiness and virtue: happiness is satisfaction of our empirical, natural inclinations, our appetites, while virtue is obedience to the moral law. Happiness belongs to the order of nature, while virtue belongs to the order of freedom.

Having separated the two realms of nature and freedom, Kant tries to reunite them by producing relations and correspondences between them. Kant’s politics may be understood on the basis of his morality, and his morality may be understood on the basis of his politics. Kant repeatedly acknowledges his debt to Rousseau for his political and moral doctrines. The priority of the practical (the ethical) over the theoretical, of the moral over the intellectual, its superiority over science and philosophy, is held by Kant to be the “voice of duty” in the soul of the simple citizen.

We need to examine this “voice of duty” more closely because in her book The Banality of Evil: Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt asserts that Eichmann claimed he did what he did (being one of those primarily responsible for the murder of six million Jews in the Jewish Holocaust during WW2) because he was following his “voice of duty” as he had heard it and learned it through Kant. Eichmann conceived of himself as “the good citizen” of the German Third Reich. and the psychologists who examined him all lauded his concern for his family, among other things: he was no “moral monster”. But for the majority of human beings, the Third Reich was “the worst of all possible regimes” which would, in turn, produce the worst of all possible human beings, the “worst citizens”. Does this problem of the moral inadequacy in our perception of the “good citizen” rest with Eichmann or with Kant? Arendt claims that what she was able to perceive in Eichmann was “an incredible inability to think” and because of this inability to think, an inability to act independently. Such statements are, of course, “value judgements” and, as such, are forbidden to The Human Sciences since one cannot make judgements on the is and the ought i.e. one cannot make judgments about what should be based on the “facts” of what is. A great number of problems arise from the consequences of such thinking if thinking is what it is i.e. we are incapable of passing judgement on Eichmann.

Kant’s political and moral doctrines are indebted to Rousseau. His “voice of duty” comes from Rousseau’s First Discourse, his notions of liberty as obedience to self-prescribed law based on reason and the generalization of particular desires as guaranteeing their universality and legality, are from the Social Contract, and his philosophy of history is taken from Rousseau’s second Discourse on the Origin of Inequality. Kant’s opening sentence to his Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals echoes and is indebted to Rousseau: “Nothing can possibly be conceived in the world, or even out of it, which can be called good without qualification except a good will.” The good will as the good in itself is the highest good and it replaces both God and nature as possible sources of our knowledge and understanding of the Good. In the good will, the humble individual who submits to the law to the utmost is raised, through the goodness of will, to an unprecedented sovereignty. It is in Kant that humanism reaches its height. It is through such submission to the moral law that one experiences one’s freedom. In Kant one sees an attempt to fuse Christian charity (action and ethics) and Greek virtue to arrive at what he conceives to be the highest human being. (See introduction to Part I.)

Kant’s revolutionary doctrine of the priority and substance of morality in the good will has many political implications. First, it powerfully supports the belief in human equality, disparaging the various natural and social (empirical) sources of inequality and demonstrating a human being’s distinction depends entirely on the quality of his moral character. Every person can have a good will and it is the only thing needful and the only thing good in itself. From this good will proceeds the universal principle of Kant’s categorical imperative: “Act so that the maxim of your action might be elevated by your will to be a universal law of nature”. Human beings create their own laws and their own morality in their freedom. These creations have become known as our “values” (CT 3); and while for Kant these were to be “universal laws”, we today view them as “subjective” and relate them only to the individual because of the dominance of the “phenomenal” in our thinking which came about through the discoveries of 19th century science. Our laws that we have prescribed to nature are our “facts” (phenomenal); those that we have ascribed to our morality are our “values” (noumenal). We do not perceive our noumenal “values” as “facts”, although Kant asserted that morality was the “only fact of Reason” and that the world of phenomenal discoveries were simply interpretations.

This result of what we have come to mean by values is, of course, not how Kant envisioned it. The maxims based on Reason which governed actions were not to become impotent as “values” and be left to the discretion of various regimes to decide through their lawmaking or their enforcement. The maxims of Reason were obligations that existed between individuals and societies whether they were recognized or not. Did Kant underestimate the power of the appetites and what would become of those appetites when they were united with the power of the human will? To put it another way, did Kant underestimate the power of the irrational and in doing so, come to misunderstand what Rousseau was actually saying?

We have mentioned in the final comments to Part I of this section of this blog the impossibility of holding together an ahistorical account of morality with the historical account of nature given in the modern sciences. Kant was aware of this problem. How did he overcome it? Kant overcame the problem by equating the Necessary with the Good, thus overturning Plato, and thus beginning what we call “the age of progress”. Nature’s determinism is a machine (to use Newton’s term) that moves imperceptively towards the good.

Kant must show how the anarchy and injustice that human life projects and the unpredictability of the human will are driven by a conception of progress having both the purposiveness that he associates with morality and the good will with the Necessity corresponding to the physical determinism of Nature. Here Kant’s debt to Rousseau shows itself: for Kant, Rousseau is the Newton of the moral world. As Newton had demonstrated a physical world of simplicity and order marred by chance and contingency which could be overcome through human intervention as domination and control of chance (technology), Rousseau perceived for the first time how the multiplicity of the appearances of human nature, the multivarious human personalities, reflected a singular human nature whose hidden law in turn reflected Providence itself. There is a natural historical progression in the moral improvement of human beings which manifested itself in civilization and culture and directed itself towards a final human perfectibility. This is a great step: if savages were ignorant of the moral law, it was because reason had not yet sufficiently evolved within them. Both morality and nature are historical and they imperceptibly progress towards a final perfection of human being.

Kant’s philosophy of history is practical; it is a guide to actions. Historical progress, for Kant, does not come about through any particular action of human beings; it is a product of Nature’s mechanism rather than the product of any individual human consciousness. The task of theoretical reason is to show that the impossibility of progress cannot be demonstrated by an appeal to experience or empirical “facts”.

Kant does not assert that human beings have a duty to believe in the attainability of the ends of progress (“international mindedness”, for instance). The duty of human beings is to behave consistently with the desire for those ends as long as their unattainability is not certain. For Kant, once moral reason lays down the veto on war, for instance, the question of whether “perpetual peace” is attainable or not is replaced by the duty to act as if it were attainable and to create domestic and international institutions that this end demands (i.e. The United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, etc.) It is moral reason which liberates us from the dogmatism of theoretical or scientific reason and prevents us from becoming “mere beasts” submitting to the mechanism of nature. Kant demonstrates through his philosophy of history that there is no essential conflict between virtue and happiness, morality and nature, morality and politics, or duty and self-interest. Human beings are building unconsciously a societal structure whose perfection they will not be able to share. Like Moses, they may see but never set foot in the Promised Land. Kant’s philosophy of history directs our gaze towards the future, a future that is inevitable through Nature’s designs. Kant’s morality requires a new way of viewing nature, what we understand as experience, and what we understand as history. Morality is the one fact of Reason.

Kant is the first philosopher in the West to make the autonomy of the will central to morality. With regard to the establishment of society, he remains within the tradition of contractualism established by Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau. In his first supplement to Perpetual Peace he writes: ‘The problem of organizing a state, however hard it may seem, can be solved even for a race of devils, if only they are rational (intelligent)’. Whereas Machiavelli, Bacon, Hobbes, Locke and Hume seemed to be emancipating human beings from the past because they turned from the eternal to things more immediate and ordinary such as self-preservation, survival, control of nature, etc., Kant’s emancipation deals with the highest things in human beings i.e. morality, freedom, and so on. It then became necessary for empiricism to adopt some of the metaphysics and ontology of Kant, for Kant’s theoretical (the phenomenal view of science) and his practical thought (the “good will” as the foundation for morality–the noumenal) were fused together. Kant’s thinking defines what is in a way that is the essential fact of modernity, of who and what we are.

Kant interprets Nature teleologically, that is morally, in that Nature’s end or purpose is the perfectibility of human beings through the use of their reason and their wills in freedom. Human beings set out from themselves and for themselves. Justice is commanded of us through the categorical imperative, and this justice is quite other than what we can know with certainty. Both Kant’s understanding of the phenomenal and noumenal worlds are a willing in that the summonsing of objects before us to give us their reasons through our use of the principle of reason (Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is dedicated to Francis Bacon), and the realization of the categorical imperative rationally arrived at and willed into being are both products of human willing. Kant, through his categorical imperative, attempts to delay the account of justice which his science outlines and reverts to a more ancient account of justice. This is the reason why the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche called Kant “the great delayer”, for the “will to power” which issues forth from the sciences is an inevitability in how human beings will come to define themselves in the future. Kant’s own providential view of Nature assures us of this. Nietzsche does not say “God does not exist” but “God is dead”, and He is dead because He is no longer needed for human beings as an horizon, or an end and purpose for their willing. It is human beings in the name of their freedom who have killed God.

Suggested Readings

Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. http://www.inp.uw.edu.pl/mdsie/Political_Thought/Kant%20-%20groundwork%20for%20the%20metaphysics%20of%20morals%20with%20essays.pdf

Kant, Immanuel. On Perpetual Peace. http://fs2.american.edu/dfagel/www/Class%20Readings/Kant/Immanuel%20Kant,%20_Perpetual%20Peace_.pdf

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. “Transcendental Dialectic” bk. I sec. I http://strangebeautiful.com/other-texts/kant-first-critique-cambridge.pdf

Georg W. F. Hegel (1770 -1831)

“The owl of Minerva takes flight only at dusk.”–Hegel, “Philosophy of Right”

The German philosopher Hegel in his work Phenomenology of Spirit illustrates an answer to the development of personal knowledge and its growth towards what he called Absolute knowledge. Like the titles of Descartes’ works which show the steps that thought must take if it is to become “knowledge”, the works of Hegel illustrate “the journey” of how the individual self receives its induction or education to knowledge so that it can realize and arrive at the standpoint of purely conceptual thought from which what he called philosophy or thinking could be done.

The works of Hegel are a Bildungsroman (“a growing up story”, an “educational novel”). This genre of writing, having a universally conceived protagonist or hero, “the hero of a thousand faces”—the bearer of an evolving series of so-called shapes or states of consciousness or the inhabitant of a series of successive phenomenal worlds, is involved in a journey of progress which eventually leads to their “growing up”. The hero or protagonist, whose progress and set-backs the reader follows and learns from, proceeds from a state of “innocence”, pre-scientific knowledge or naivety, to one of “experience”, whether in the Romantic journeys of a hero such as Frodo in The Lord of the Rings or in the nihilistic journeys of the modern French writer Louis Ferdinand Celine. The individual self or the shapes/states of consciousness that are its personal experiences, its “personal knowledge”, later becomes replaced with configurations of human social life or communities. “Personal knowledge” was perceived as “subjective knowledge” by Hegel and this kind of knowledge led to the “objective knowledge” that living in communities provided for the individual. We have called this our “shared knowledge” in the constructs of the TOK course.

Hegel and his works show a progression (like those of Descartes) from The Phenomenology of Spirit to The Science of Logic to the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences to the Elements of the Philosophy of Right. The works progress from the particular to the universal, from the individual to the social, from personal to shared knowledge. The interlinked forms of social existence and thought within which participants in such forms of social life conceive of themselves and the world is the journey of Hegel’s work. Hegel goes on to show how this journey, understood as History, illustrates the direction of Western thought from the Greeks to the 19th century European sciences in his works after Phenomenology of Spirit.

For our purposes, we wish to understand Hegel’s term “Absolute knowledge” and how it relates to our understanding of who and what we are, both as individuals and as societies. This will be our focus here. We will see a close connection between Hegel’s thought and Kant’s “transcendental methodology”.

The journey of the Self is represented by Hegel in four stages: 1. consciousness; 2. self-consciousness; 3. reason/logic; 4. Spirit. The four stages correspond to the titles of Hegel’s texts moving from Phenomenology to Elements, from personal knowledge to shared knowledge. The stages are a process or a movement: consciousness > self-consciousness > logic or reason > elements of right. The movement is from the individual or particular to the universal or general, from subjective to objective, from the individual to the community, from theoretical to ethical thought or what was called phronesis by the Greeks, although Hegel’s conception of ethical thought is quite different from the ancients.

The first stage is how the new guidelines for May 2022 are presented to us: consciousness or personal knowledge and its contents or shared knowledge (here “shared knowledge” is coeval with the term History) is the “core theme”. Consciousness at this “subjective” stage is already “absolute knowledge” for Hegel, but this knowledge is “alienated” from its contents in a negative way; there is a gap between how the individual consciousness and its objects are related to each other. For that gap to be overcome, consciousness must proceed to the second stage and view itself as self-consciousness, the ego cogito of Descartes. This movement can be viewed as creating the “open region” where the “space” is made available for the objects to come to presence as objects and we can make statements about them that will take the form of propositions like “I know because…” and “we know because…” In this “space”, reason and logic are used to arrive at “objective knowledge” of the things that are.

For Hegel, “knowledge is the relation of the being of something for a consciousness” and this is why the title of Hegel’s second text is Science of Logic. It is through “logic”, the principle of reason, that beings/things get their “being” through human consciousness. Knowledge is itself a way of knowing and comprises all the other ways of knowing (what has been called “technology” in these writings). It is the “immediate knowing” that occurs through our sense perceptions and encounters with objects. At this stage consciousness must detach itself from the object it knows “mediatively”, that is through the various ways of knowing the object, in order to recognize that that which it knows is only a means towards “self-consciousness”. Hegel uses the plural pronoun “we” to describe these knowers. They are those who know “absolutely”, and they are the ones who are “empowered” in today’s language.

As it was for Kant, Reason and History are inseparable for Hegel. The historical process is fundamentally rational since it is human beings who consciously make their history in their free actions. It is only human beings as a species who are consciously aware of time and its passing. In their political actions, it is only through the state that the individual can achieve universality and, thus, achieve their true “reality” in “absolute knowledge”. Only the state can act universally by instituting laws. Morality, which seeks universality, can only be actualized through its realization in the institutions and education of the state. It is the state which determines the character of its members and this character is determined by the morals and manners (habits) which the individual gains through their education within the state. As it is with Kant’s thinking, it is the individual’s devotion to the state which assists their going beyond primitive spontaneous selfishness. Hegel relates the story of a father who asked a Pythagorean how to best raise his son morally, and the Pythagorean responded: “Make him a citizen of a state which has good laws.”

It is in Hegel where we find the concept of the universal and homogeneous state or “the final state” where the individual finds in it the truth of their existence, their duty, and their satisfaction, and where the state actualizes Reason in the external world. The relation between the individual and the state is reciprocal; the state finds its end or purpose in the enhancement of the individual’s liberty and satisfaction. In the state the individual goes beyond their mere primitive personal thoughts and wishes (which Hegel calls “the subjective mind” or “self-consciousness”) and learns, through reason and logic, to universalize their wishes to make them into laws and to live according to them. This reason/logic is Hegel’s “objective mind” or the third stage of the individual’s journey and growth.

The fourth stage, the “absolute mind” is made possible by the state. The state is the source of art, religion, and philosophy (shared knowledge or “culture”) which in themselves transcend the state. The state is fundamentally informed by rationality, but this rationality is not beyond its time but is a product of its time. Hegel’s philosophy of history is historicism, a view which now dominates all our thinking and research or what is called our “shared knowledge”. The task of philosophy is to unfold the positive truth which is already present in reality, to bring this truth to unconcealment. Hegel wants to show that what is irrational and contradictory will finally be brought into harmony in the universally just and fully developed political order, the universal and homogeneous state where “absolute mind” is realized. The “final state” is in the natural order of things and political philosophy, philosophy itself, is transformed into the philosophy of history.

Human beings in the first stage of their journeys are caught up in a great struggle for “recognition”: the human being exists for themselves, is conscious of their person or their own freedom only to the extent that their consciousness and freedom are recognized as such by another human being. Because of the fear of violent death, one human being will consent to recognize the other without being recognized by that other. From this fight for recognition emerges the master-slave relation. This is the condition from which states emerged and the conflict itself is prior to the emergence of states. It is the equivalent of the state of nature in Hobbes; the vanity that is the desire for recognition and the fear of violent death.

For Hegel, it is the master-slave relationship that is the driving force of human history. The master forces the slave to work for him; and being idle himself, the master’s life is spent in the quest for recognition, prestige and glory through war. The slave does the work preparing things to satisfy the master’s needs, and in doing so transforms nature and himself. It is through the slave’s work that both the world of technique and society as the world of thought, art, religion (culture) are constituted. In the classical tradition, leisure had a higher dignity than work because it allowed the theoretical life to be possible, and the theoretical life was considered superior to the practical life. For Hegel, thought and the universal are on the side of work since it is through work that the plan of the techne can be realized through production; leisure is essentially warlike.

Neither the slave nor the master is satisfied in that the desire for recognition by another consciousness is not fulfilled for both. It is the state’s purpose to repair this situation. There is a tension between the “bourgeois” and the “citizen”, “civil society” and the state. The master/slave tension must be resolved. The conflict was viewed by Hegel as that between “subjective liberty” (individual consciousness and will pursuing its own goals) and “objective liberty” (the “general will”). Hegel says that “the union of the particular and the universal in the state is that upon which everything depends”. This “unity of its final universal end and the particular interests of the individual” is that “they have duties to the state in proportion as they have rights against it”. The right of consciousness is to recognize nothing of which it does not approve rationally.

Hegel makes distinct the difference between ancient and modern accounts of politics: “The right of the subject’s particularity, his right to be satisfied, is the pivot and centre of the difference between ancient and modern times.” The French Revolution was a great historical achievement for its decision to put thought and reason at the foundation of the state bringing about “subjective consciousness” and with it all the principles of liberty, equality, and the rights of human beings and citizens. But the revolution required Napoleon to bring together the abstract principles of individualism with the concrete form of the state. Individualism only brings upheaval, and individual liberties and rights as well as juridical equality does not ensure or lead to democracy. The individual should only be taken into account when he occupies a definite place in the organism that is the state, according to Hegel.

A word of explanation on the distinction between “abstract” and “concrete” is required here. One reaches the “abstract” when one “skips over” or abstracts from some features implied in the “concrete” or “the real”. When I am speaking of a tree, for instance, each individual upon hearing that will abstract everything that is not a tree (the earth, the air, the sun, etc.) and perceive an “abstraction”, an “idea” that does not exist in reality for the tree can only exist if there is earth, air, sun, etc. Hence, all particular sciences deal in varying degrees with abstractions and this allows for the application of mathematics in realizing their “particulars” or objects of study. The isolated “particular” is by definition abstract. The journey of the mind is an attempt to rise to the “general ideas” beyond the abstractions, the “universals” which are the concrete or “the real”.

For Hegel, the modern state should represent a synthesis of the Greek polis (of which the unity, the citizens’ mutual confidence and their attachment to the whole, should be preserved) and the liberal society of political economy (the diversity and differentiation of individuals, the satisfaction of individual needs, the realization of the universal by the individual’s free will, should be preserved). Hegel wishes to effect a synthesis of classical morality with the Christian-Kantian morality, of the politics of Plato founded on the primacy of reason and virtue, and the politics of Machiavelli, Bacon, Hobbes, and Locke founded on the emancipation of the passions and their satisfaction.

History is the means of this synthesis. The end of history is the progressive revelation of freedom, the consciousness which the mind gains of itself through history. Freedom is now the essence of human being. This recognition of human being’s and freedom’s essence will only occur at the end of history since history is made up of the progressive appearances of incomplete principles, each one showing a new aspect of freedom, but each one being doomed because of its incompleteness. The “final state”, the universal and homogeneous state, which is the product of “absolute mind” or “spirit” will be that historical moment when reason will find its completeness or perfection.

The progress of history occurs in three stages: 1. those societies which are barbaric because they do not recognize that they are free human beings and are merely individual consciousness; 2. the Greek society where consciousness of freedom first came to light; and 3. the Germanic societies where, through Protestant Christianity human beings recognize that spiritual freedom constitutes the nature of human beings. The Greek society’s lack of development and diversity (call it, if you will, technology) in contrast to the modern state’s foundations in Protestant Christianity and an economically and socially differentiated society illustrated, for Hegel, the superiority of the modern state.

It is only in the Protestant Christian society that the infinite worth of the individual makes its appearance. Only in Protestant Christianity is freedom actualized and effects its reconciliation with the world and the state. In Protestantism, there is no class of priests but a universal priesthood where the individual consciousness has the right to judge with regard to moral matters. This is eventually transformed into the right of the individual reason to judge with regard to the things of this world. In Protestantism arises the principle of the free mind: human beings decide by themselves to be free. In this process, the rational state can be constituted by leading “subjective freedom” to universality. Truth resides in the subject as such to the exclusion of all external authority. This, ultimately, includes both God and Nature as an external authorities.

By abolishing the difference between the eternal world of religion and the temporal world of the secular, religion is done away with while being fulfilled. Protestantism signifies the Christianization of the secular and the secularization of Christianity. While the modern state has Protestant Christian roots, it is accessible to all human beings in the principle of rational universality. Despite Napoleon’s efforts, the modern principle failed in Latin countries because they were Catholic: subjection to religion brings political servitude. This secularization is the first fundamental principle of the rational state.

The second fundamental of the principle of the rational state (which is universal and homogeneous) is economic and social differentiation based on the liberation of individual wants and needs. Because individual circumstances and needs are so multivarious, they make necessary the requirements for universal law. Hegel felt that there was not yet a true state in North America, for instance, because there was an absence of economic and social tension, the class struggle based as it is on the master-slave relationship, a requirement for the next stage. The development of this tension is historically inevitable in Hegel’s thinking. Perhaps one could say that 150 years after Hegel, North America has realized that tension in the present. Then again, one may not.

How is the individual connected to the universal? For Hegel, the family is the first basis of the state and they are related to “the agricultural class” because they provide for substantial, immediate basic needs such as food, shelter, sexuality, “security” and their satisfaction; these are “universals” for Hegel because they are things that all human beings need. The second basis of the state are “general groups” or “the industrial class” which is the reflective class since it provides the techne and the products necessary for the leisure of the bourgeois. The third class is the class of “civil servants” who are related to the state and find their purpose and satisfaction in the state.

Virtue in the modern represents the individual’s adaptations to the necessities of the situations in which they happen to find themselves. The state itself, representing the whole, will realize its completion in a “constitutional monarchy”. The universal and homogeneous state is the result of the historical progress of the modern world. The object of universal history is the formation of the state wherein “absolute knowledge” is realized. Plato’s traditional classification of monarchy, aristocracy, oligarchy, democracy and tyranny are the historical products of “undifferentiated society”.

In the “final state”, the sovereignty of the state is realized as will in the person of the “universal monarch” or “universal despot”. Whether the final ruler is monarchic or despotic “is not important for the force of the state is in its reason”. Who exercises this “reason”? The government will exercise its reason through its universal class of civil servants, what we today call the “bureaucracy”. The democratic aspect of the rational state is that all its citizens can become civil servants and members of the bureaucracy. The civil servant represents the spirit of the regime. He replaces the aristocracy of the old order. The civil servant is the embodiment of the systematized and rationalized form of the government of the best, the end product of the framing and the ordering of technology.

The universal and homogeneous state is the best social order or regime according to Hegel, and human beings advance to the establishment of such a social order through work. Alexander the Great, the pupil of Aristotle, was the first ruler who met with success in realizing a universal state, an empire, because he recognized that human beings shared a common “essence”, and that essence was what we call “civilization”, the product of reason, the culture of the Greeks which was the culture of reason itself. But Alexander could not overcome the distinction between masters and slaves. His universal state could not be a society without classes.

Class distinctions were overcome through Semitic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) and their belief in one God. But it was Protestant Christianity which emphasized the centrality of the individual human conscience and the human soul and in doing so negated Christian theism. As a consequence of this, the drive to the universal and homogeneous state remains the dominant ethical “ideal” to which our contemporary society appeals for meaning in its activities (CT 3). It is only through the negation of theism that it is possible to assert that there is progress, that is, that there is any sense or rationality or overall direction to history.

The realization of the universal and homogeneous state will involve the end of philosophy. The love of wisdom will disappear because human beings will be able to achieve wisdom or “absolute knowledge”. But in political terms, the universal and homogeneous state will also, necessarily, be a tyranny (if it is realized) and, if Plato is correct, as a tyranny it will be destructive of humanity. As we have seen here in our journey through modern political science and the historical development of The Human Sciences, the substitution of freedom for virtue has as its chief ideal, an ideal which it considers realizable, a social order which is destructive of humanity. The technological realizes its end in the “technology of the helmsman” who will be, by necessity, a universal despot, and with the conquering of nature, this end will be the realization of cybernetics, the unlimited mastery of human beings over other human beings.

Suggested Readings

Hegel, G. W. F. Philosophy of Right. Preface, Third Part http://www.inp.uw.edu.pl/mdsie/Political_Thought/Hegel%20Phil%20of%20Right.pdf

Hegel, G. W. F. Philosophy of History. Introduction; part II: “The Greek World”; part III chap. ii: “Christianity”; part IV sec. III, chap. i “Reformation”; chap. iii: “Enlightenment and Revolution”. https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/econ/ugcm/3ll3/hegel/history.pdf

Hegel, G. W. F. Phenomenology of Mind. Chap. iv.. Sec. A: “The Master and the Slave”. http://www.faculty.umb.edu/gary_zabel/Courses/Marxist_Philosophy/Hegel_and_Feuerbach_files/Hegel-Phenomenology-of-Spirit.pdf (This is a challenged translation of the original, but it is probably the most popular text among translations of this work.)

Karl Marx (1818-1883)

Marxism presents itself as a comprehensive account of Being, that is, of both human life and Nature itself. It does so through a concept of time which is understood as History, and History understood as the evolution of the endless changes and modifications of things in Time, or what is called Becoming.

In his economic writings, Marx provides both his accounts of the present and also his teaching on history and metaphysics which provides his political philosophy or his account of societies or The Human Sciences in general. Marx’s philosophy of history is found in his earlier writings, particularly The German Ideology. His account of the present is found in his major work Das Kapital or Capital. It is through Marx and marxism that the technology of the humanist religion of the age of progress, a Western European ideal or “ideology”, reached Asia and flourished there. Why has this been the case, and how does it show the truth of the assertion that communism and capitalism are predicates of the subject technology?

Marx’s Das Kapital consciously follows the structure of Hegel’s Science of Logic with its scheme of being, essence, and idea. We will look at Marx’s political philosophy and his view of the Human Sciences in this manner: 1. a few comments on his dialectical materialism, or Marx’s theory of history and of the priority of the economic conditions within it; 2. some very brief comments on his labour theory of value and Marx’s account of the capitalistic present; 3. the convergence of the labour theory of value and dialectical materialism in the universal socialist state. The most important reflections are the comments on technology’s relation to the modes and means of production. We shall focus on Marx and not on his collaborator Friedrich Engels in our attempts to access Marx’s thought.

To begin, Marx was a Machiavellian in his politics. He repeatedly asserts that the study of human beings must concern itself with “real” human beings, not with human beings as imagined or hoped for or believed to be. Like Machiavelli he, too, believed that the good political end justifies any means. The foundation of The Human Sciences, the domain and the object of study, is not an idea of some wished-for human good such as one finds in Kant, or some reconstruction of “pure” natural human being that one finds in the thinking of Rousseau, but rather empirical human being as anyone could at any time observe him.

Empirical human being is a living organism consuming food, clothing, shelter, fuel, etc. and is compelled by nature to find or produce those things. Human beings may have begun as hunters/gatherers, but with the increase in population they were compelled to produce their necessities and thereby become distinguished from the beasts; they became agriculturalists in other words. The distinguishing feature of humanity, according to Marx, is conscious production–not rationality or political life as some maintained. But there is a lack of clarity in Marx’s writings upon this point: he concedes that human production differs from the “production” of bees or insects in that human being plans or conceives in advance the completed object of their labour (what we have been calling technology in these writings). Only human production, according to Marx, is characterized by rational intention and is, thus, unique in being the product of the rational animal.

Marx distinguishes the instruments or tools of technology from the technology itself. We could say that given Marx’s assertion, he would be more precise to say that rationality rather than production is more characteristic of the nature of human being, but Marx is prevented from doing so because the implications of that assertion would interfere with his materialism which argues that human beings’ rationality or “consciousness” is not fundamental but derivative. They are historical. These are the metaphysics that Marx learned from Rousseau. The primacy of production rests upon the presence of human beings’ needs that force them to continue to press onward to overcome those needs; and the content of human beings’ rationality is determined by conditions external to reason i.e. the necessary conditions which are strictly “material”, the external world. To overcome their needs and to enhance their security, human beings are compelled to conquer necessity and chance i.e. nature, including their own human nature. Marx learns from Hobbes that the scarcity present in nature brings about a competition which in turn brings a fear of violent death in the strife that is present for meeting the basic needs.

How do “material conditions” determine life and thought according to Marx? Marx begins by observing that in every epoch human beings have access to productive forces (the tools of technology), but these productive forces compel human beings to adapt themselves and their institutions to the requirements of that technology or those productive forces. We find many examples today of the conflict between the new technologies and our prevailing institutions. The conditions of production determine the prevailing property relations and social class structures at any given time: the waterwheel gives the serf/feudal lord; the steam engine gives the labourer/capitalist industrialist. Marx asserts that there are no “essences” to prevailing economic concepts such as consumption, distribution, exchange, money, etc. The understanding of these concepts as “permanent” is one of the defects of “bourgeois economics” that views historical phenomena as fixed categories having an “objective, essential, natural character” i.e. things to be understood once and for all because they exist once and for all. For Marx, all “categories” are historical products and the economics that believes in them proves itself to be merely historical by mistaking the transitory for the eternally true i.e. believing in laws supposedly founded in a changeless nature. It is the historical conditions that determine the definitions, suppositions and pre-suppositions of the concepts.

The economic science of capitalism is given its “categories” (wages, interest, profit, exchange, etc.) by the practices prevalent under capitalist production, and it takes up these categories without recognizing them as the products of their historical material conditions. Marx’s belief in the dependence of theories on historical conditions of production applies not only to economic theory but to morality, philosophy, religion and politics which depend on the environments that human beings have made through their determination of the modes of production. Marx does not believe that thought has independent status, and in this belief turns Hegel, his teacher, upside down. The essence of human beings, what human beings are at any given time, is determined by the conditions of production or the “material conditions” of their environments. The goodness or badness of human beings is dependent upon the nature of these material foundations. Existence precedes essence; human beings are perfectly malleable and can shape themselves or will be shaped given the changes (evolution) based on these historical material conditions.

The modes of production, how things will be produced and brought forth, have been the possession of the few and have not been shared by all human beings. The many have had to give the only thing they’ve got, their capacity for work, in order to gain a livelihood. All previous history shows the many dependent on the few, and their dehumanization is compounded by the poverty imposed upon them by their exploiters. Marx applies his “dialectical materialism” to the concepts of value, exchange, labour, profit, and work. All value is essentially energy. Work can be measured in units of time according to the length of its duration in the production of a commodity which will, in turn, determine its value. A commodity is a good privately produced for the sake of exchange or money. Money is congealed energy, congealed work. Rationally, the sum of all the individual labour in the community and the labour-power of the community itself should be adequate to satisfy all its wants and needs. What Adam Smith regarded as the peculiar virtue of private enterprise i.e. the voluntary performance of a social function under the desire for private advantage, is regarded by Marx as the ground of evil and instability in the prevailing capitalist system and its communities.

The study of Marx has been discouraged or even been given a hostile reception in the empires of capitalism, Britain and North America, but Marx is worth studying not only because of his influence in the history of Asia but also because he is a social theorist of the first rank who illustrates to us the diverse currents of that river that is the age of progress. It must be recognized that marxism (not capitalized here for the reasons which follow) is much profounder than those limited canals dug by the apparatchiks of the Communist Party in the East or West. As is the case with all great prophets, his disciples have consistently neglected and misinterpreted those aspects of his thought that did not serve their purposes. Marx must be studied because as a theorist he brought together the various streams of humanist thought, and in synthesizing them showed clearly to us the the doctrine of progress that gives meaning to and dominates our present learning.

Marx is essentially a philosopher of history, one who believes he knows the meaning of the historical process as a whole and derives his view of right action therefrom i.e. ethics, morality and justice. As we have seen in both Kant and Hegel, the philosopher of history replaces the old priesthood in attempting to vindicate divine providence in view of the existence of evil. Our search for meaning becomes necessary when we are faced with evil in all its negativity. Marx’s starting point is the indubitable fact of evil; reality is not as it should be. Human beings are not able to live properly because their lives are filled with starvation, exploitation, greed, and the domination of one human being by another. No thinker ever had a more passionate hatred of the evils that human beings inflict upon each other and that such evils should cease in the name of justice. To overcome the despair that exposure to overwhelming evil can bring, Marx developed his criticism of traditional religion and his theory of “dialectical materialism”.

Marx’s critique of traditional religion focuses on the traditional solution to the problem of evil. The falsity of that traditional belief is that it is based on the belief that all is really well and this has prevented human beings from dealing with the evils of the world. The idea that there is a God who is finally responsible holds human beings from taking their responsibility to eradicate evil seriously. If there is going to be pie in the sky when you die, then the evils of the world are not finally important. Religion is the opium of the people, as Marx says. To pretend that all is well is to disregard the suffering of others. The first task of thought must be the destruction of the idea of God in human consciousness.

Marx’s position is stated clearly: “Philosophers up to now have been concerned with understanding the world; we are concerned with changing it”. What Marx is saying is that traditional philosophy has sought the meaning of the world that is already present; Marx is concerned with the creation of meaning in the future of human beings. In order to do so, human beings must take their fates into their own hands and overcome the idea of God. Marx recognizes that if human beings are to pass beyond belief in God, religion must not only be denied but its truth must be taken up to buttress the humanist hope. Christianity’s truth, its “values”, must be secularized. This truth was the human desire to overcome the evil in its own nature, or to overcome its own “alienation”. “Alienation” is the condition of human beings in society that estranges them from the fulfillment of their freedom. The religious yearning to overcome evil will be fulfilled by human beings in history; history is where evil will be overcome.