Technology as Information

We will be discussing how “mathematics” provides the principles for our actions i.e. how mathematics determines our ethics. We shall examine some considerations of the differences between what is called calculative thinking and what is called contemplative thinking. In this examination we will come to a closer understanding our technological being-in-the-world. Mathematics is understood as “what can be learned and what can be taught”.

What we call mathematics is a theoretical viewing of the world which establishes the surety and certainty of the world through calculation. Calculative thinking determines that the things of the world are disposables and are to be used by human beings in their various dispositions. This commandeering challenging of the world and the beings in it is what we have come to call “knowledge”, and is made possible by what we call “knowledge”. This under-standing (i.e. that which “stands under” or grounds) is that upon which all of our actions are based. This surety or certainty that beings are in the way that we say they are through calculation arises through the viewing and use of algebraic calculation in the modern world. Algebraic calculation is a language of signs and numbers. The results of what is and what has been achieved through this calculative thinking are what we have come to determine what knowledge is in our day and what is best to be known and how it is to be known. What is the relationship between these calculations and what we call “information” and how does information relate to ethics?

Ethics are based on what Aristotle called phronesis: our careful deliberation over what best actions will ultimately bring about the best end result. We call this end result our happiness or what Aristotle called our eudaimonia. But how can happiness be the end result of what is, essentially, a hubristic way of viewing and being in the world? What we choose to be through our doings in the worlds of our projections is that which demonstrates our skills, aptitudes, and fitness to bring forth the “work” that is the “product” or outcome of the activities in those worlds whether those outcomes or “goods” be works, services or ideas. It is eros that urges the soul to “hear” that calling from the logos that sets us upon the journey to self-knowledge that allows us to adapt to the inevitable change that is a re-birth that seeks for that which is fitting to the soul.

A Reading of King Lear

We shall reflect on this question of self-knowledge and how the mathematical impacts self-knowledge by examining the passage below from Shakespeare’s King Lear Act V sc. iii.

CORDELIA

We are not the first

Who, with best meaning, have incurr’d the worst.

For thee, oppressed king, am I cast down;

Myself could else out-frown false fortune’s frown.

Shall we not see these daughters and these

sisters?

KING LEAR

No, no, no, no! Come, let’s away to prison:

We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too,

Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out;

And take upon’s the mystery of things,

As if we were God’s spies: and we’ll wear out,

In a wall’d prison, packs and sects of great ones,

That ebb and flow by the moon.

EDMUND

Take them away.

KING LEAR

Upon such sacrifices, my Cordelia,

The gods themselves throw incense. Have I caught thee?

He that parts us shall bring a brand from heaven,

And fire us hence like foxes. Wipe thine eyes;

The good-years shall devour them, flesh and fell,

Ere they shall make us weep: we’ll see ’em starve

first. Come.

Explication of the Passage from King Lear

To attempt a summary and explication of the whole of the greatest work in the English language is impertinent. But a brief introduction is necessary to understand the play as it appears in the scene above.

At this point in the play, Lear and Cordelia, supported by French troops, have lost the civil war for Britain to Edmund’s forces. Lear, as King, has been ultimately responsible for this civil war. At the beginning of the play, he has disowned his ‘truthful’ daughter Cordelia and fallen victim to the flattery and machinations of his two eldest daughters, Goneril and Regan. He has divided the kingdom in two giving each sister control of half, the intention being to avert future strife. Lear, at the same time, wishes to retain the appurtenances of a king, the appearances of a king, while retaining none of the responsibility: Lear is satisfied with the appearances rather than the realities of things. It is this satisfaction with the appearance of things that leaves Lear open to the machinations of his two daughters, Goneril and Regan.

Lear’s responsibility is, chiefly, a moral one. Goneril and Regan soon work together to remove from Lear the power and possessions that he once held. Lear becomes an “O”, “a nothing”. In his “nothingness”, Lear becomes mad and rages against the ingratitude shown by his daughters and the injustice that he sees in the nature of things and in the created world as it is.

This scene from Act V above is Lear’s anagnorisis or moment of enlightenment, the moment in tragedies when all tragic heroes recognize the errors of their ways and the consequences of their hubris. These consequences we call nemesis or just desserts.

Lear ends up houseless and homeless and wanders on a heath in the heart of a terrible storm. Lear’s physical, mental and spiritual sufferings soon drive him mad. The storm’s effect is a purification of Lear: Lear removes his clothing to become naked, to reveal human being as a mere ‘bare forked animal’; his ego is destroyed in the madness; he no longer focuses on himself but is able to see the ‘otherness’ of human beings and to feel compassion and pity for them (in the characters of Edgar as Poor Tom and the Fool) because he sees himself and his humanity in them. Edgar, too, has become a ‘nothing’ due to the machinations of his bastard brother Edmund and is a parallel to Lear in the double plot of the play.

Lear has gone from King to nothing and he is ready for re-birth. His ego has blinded him to understanding what his true relationship to his god is: initially he looked upon this god and his power as being something which he, Lear, himself possessed. Lear believed that only he himself possessed this truth. He dismisses the truth-tellers in the play: his Fool and his daughter Cordelia. In Lear’s kingdom, truth is not to be revealed. Only those who flatter are those that are heard.

The play King Lear is a play about the consequences of not knowing who we truly are, as individuals and as a species, as human beings. Lear, focused as he is on his ego, his Self, is willingly duped by machination in the play; he is willingly duped by flattery as this flattery is recognition of his social prestige. His later suffering and madness bring him to a true understanding of his relation to the god and to other human beings, and this relationship is Love expressed through the care and concern that he later shows to Poor Tom and the Fool. Love is, as Plato describes it, “fire catching fire”. It is recognition that in the most important things, all human beings are equal in that all are capable of the capacity for Love. Given the inhumane nature of human action in many cases in the real world, it is not without reason that Love has been described as a homeless, houseless beggar in our mythologies. Our literature sometimes refers to him as Eros.

Many critics suggest that this play is atheistic; Lear has lost his faith in God. The above passage suggests that such is not the case: what Lear has come to understand is his true relationship to his God, the true relationship of all human beings to God. Lear has lost the illusion of what he had once understood as God and what his relationship was to that God. It is this illusion that is the trap cast for those who believe that they are in possession of the truth or that truth is a product of their own creation or doing. Such a belief gives the individual the illusion of power. The God in King Lear is absent: He will not perform some miracle preventing the hangings of Cordelia and the Fool by the Captain later in the play. The essence of human being and of our humanity is to reveal truth. Great catastrophes are the result when we do not do so. In King Lear, the truth is destroyed. Good does not triumph over the evil of human actions in this play and we, too, by our very silence, are made complicit in the deaths of Cordelia and the Fool. In King Lear, human beings are not “beyond good and evil”.

In the play, the god exhibits Himself by His absence. Absence is not non-existence. It is the absence of God in the play that gives reason to those who interpret the play atheistically. One of the many themes of the play is what happens to human beings when they ignore the truth and persecute the truth-tellers. They, too, become subject to machinations and gaslighting. It is the tyrannous element present in all human beings. In their ignorance, they become victims in the struggle for power. When we show our astonishment at the discoveries of the James Webb Space Telescope, we are actually witnessing the withdrawal of the God into hiddenness in order to allow those distant galaxies to be. As Being comes to presence, the God withdraws.

The play King Lear shows that the purpose of suffering is to allow for the de-creation of our selves, the de-struction of ourselves, our “I”s or egos. We today see no purpose in suffering, particularly the suffering of the innocent. One of the purposes of suffering is the destruction of the ego or self through affliction. This same decreation of the self was behind the geometry of the Pythagoreans. For the Pythagoreans, the study of geometry served an identical purpose: the purification of our selves or souls through a contemplative understanding of the things that are. When we stand on the circumference of the sphere above and are subject to its spinning, we suffer the ups and downs of Fate. We are beings in Time. Being at the centre of the sphere allows us to be free of its spinning. The spinning of the wheel or sphere is Time.

There is a Wheel of Fortune motif that runs throughout King Lear: Fortune is personified in the passage through alliteration ‘false fortune’s frown’ to illustrate that it is, in this case, one of human making: even with the best of intentions one can incur the worst: good does not triumph over evil in this sphere but is subject to the same necessity as are rocks and stones. To decreate one’s Self is to have the Self replaced by an assimilation into the divine; it is to become one of ‘God’s spies’, to see all with God’s eyes and to see all for God. God requires human beings “to see” His creation. His creation is Necessity; and there is a great gap separating the Necessary from the Good. Being requires human beings. When a human being sacrifices the Self, the ego, his most treasured possession, for assimilation in God, “the gods themselves throw incense” upon this sacrifice. We believe our Self to be our most precious possession; the renouncing of this possession is the purpose of our lives, and this renunciation is not pleasant: it is done through suffering. Few people are capable of it. I am not sure that one would want to be the parent of a saint. It is a pain-filled event much as ‘the turning’ in Plato’s allegory of the Cave is a pain-filled event.

The centre of the sphere is both in time and space and out of time and space. The Self as center here is indifferent to the size of the prison, the size of the circle, the size of the sphere. For Lear, imprisonment will be a liberation, not a restriction. “Suffering (affliction), when it is consented to and accepted and loved, is truly a baptism” (Simone Weil, “The Love of God and Affliction”). This is similar to Hamlet’s praise of Horatio (Act III sc. ii) where Hamlet says:

“…for thou hast been

As one, in suffering all, that suffers nothing,

A man that fortune’s buffets and rewards

Hast ta’en with equal thanks: and blest are those

Whose blood and judgment are so well commingled,

That they are not a pipe for fortune’s finger

To sound what stop she please.”

Horatio has what we may call a ‘balanced soul’: each of its parts does what it is supposed to do. Having this balanced soul is what we understand as “self-knowledge”. This self-knowledge allows one to accept the buffets and rewards of fate with equal thanks. Of course, it is easy for us to be thankful for the goods that we receive from fate. It is not so easy to accept the inevitable afflictions that come with being alive with equal thanks.

Baptism is a spiritual re-birth. It is usually associated with the element of water. The purification of the soul is associated with fire, with alchemy. Love is ‘fire catching fire’. On the heath, Lear experiences both the baptism with water and the purification through fire. The spiritual rebirth for Lear is clear from this passage in Act V sc. iii as well as from Act III onwards in the play where he experiences both a physical and spiritual re-birth. In order to do so, he must lose all that has attached him to his world and his ego must be destroyed. He must, in a real sense, ‘die’ and become a ‘nothing’. This is the purpose for Lear’s nakedness and madness in the play.

The attempted suicide of Gloucester in the play due to his suffering is a counterpoint to this: suicide is a sin against the gods because we falsely believe that our self is our own and of our own making. Gloucester’s realization that this is not the case results in his finding Edgar again and having ‘his heart burst smilingly’. His death is the counterpoint to Lear’s death: Lear’s heart will break due to the depth of his affliction at the loss of his Fool and Cordelia. Death is the inevitable end for us all. Contrary to our view, in the world of Shakespeare some kinds of suffering have a purpose and some suffering simply does not, and human beings are not beyond the good and evil that is present in the suffering that has no purpose or meaning. My saying this is in opposition to that statement recently by a Republican congresswoman who said that death is inevitable in order to justify her voting for the cuts that would be made to healthcare for the poor.

Our “personal knowledge” is our ‘sphere of influence’ on our worlds and on the other human beings who inhabit our worlds. The impact of our spheres of influence will be determined by the amount of self-knowledge we possess, and on the skills, aptitudes, fitness (techne) that we possess for the tasks. Those spheres that we inhabit in our lives should be seen as composed of wheels within wheels with our actions the spokes of the wheels. The spokes are our ‘projections’ and provide support for our spheres. The spokes reach out to the circumferences of the wheels: from the diameter, the right angled triangle cannot exceed that circumference. The sphere created by the circumferences may be large or small; most of our lives are spent in our attempts to enlarge this sphere. The spokes that are the radii of the self are the whorls of a gyre initiated by the soul and projected upon the world that we are in in order to create a world. In the whorl that is the motion within our sphere, we are ’empowered’ to carry out our activities, but the prison of ourselves is still a ‘prison’ beginning with our bodies and our egos which are placated by the social prestige which comes from the fulfillment of our urges and desires. At each stage on the whorl, there is a leaping-off possibility that presents itself through the metaxu or relation of the logos.

We become and are satisfied in being the ‘poor rogues’ and ‘gilded butterflies’ that Lear and Cordelia will chat with. The outer edges of the sphere in its spinning indicate the fates of those who are ruled by Fortune: ‘who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out’. It is the fate of all of us who are dominated by the wish for social prestige, recognition. This fate and our desire for this fate is part of the ‘mystery of things’, the mystery of being: to see this we must remain at the centre of the sphere where we are not moved by the wheel’s or the sphere’s spinnings, nor are our desires dominated by the wish for social prestige and recognition.

Lear, through his madness and suffering, has been re-born (see other sections of the play particularly Lear’s awakening when he sees Cordelia as an angel, a mediator, and in the play she is, from the beginning, representative of truth). His self, ego, I, has been destroyed. He becomes a “nothing”. In this scene from Act V, Lear demonstrates the friendship that is the love between two unequal yet equal beings. Lear’s ‘kneeling down’ when asked for his blessing in order to ask for forgiveness is his recognition of this equality. It is no longer the view of the Lear who said “I am a man more sinned against than sinning”, a false view of Lear’s at the moment of its occurrence in the play for it is the view of most of us with regard to our own sufferings. We see ourselves as victims.

It is with a great and terrible irony that after these speeches of Lear’s and Cordelia’s, the following occurs:

EDMUND: Come hither, captain; hark.

Take thou this note. (30)

[Giving a paper] Go follow them to prison:

One step I have advanced thee; if thou dost

As this instructs thee, thou dost make thy way

To noble fortunes: know thou this, that men

Are as the time is: to be tender-minded (35)

Does not become a sword: thy great employment

Will not bear question; either say thou’lt do ‘t,

Or thrive by other means.

CAPTAIN: I’ll do ‘t, my lord.

EDMUND: About it; and write “happy” when thou hast done. (40)

Mark, I say, instantly; and carry it so

As I have set it down.

CAPTAIN: I cannot draw a cart, nor eat dried oats;

If it be man’s work, I’ll do ‘t.

The Captain’s final words are a statement for all of us motivated by social prestige. That Edmund should give the Captain a paper or document instructing him is a particularly ironic note. Human crime or neglect is the cause of most suffering. On the orders of superiors we carry out acts that we believe are “man’s work” i.e. they are not the work of Nature but we ascribe the moral necessity for our actions to Nature: “I cannot draw a cart, nor eat dried oats”. We believe that we are compelled to commit immoral actions because we believe Nature imposes its necessities upon us; and, at times, Nature does indeed do so. We believe such actions to be our ‘duty’. But if we live with a thoughtful recognition that there are simply acts which we cannot and must not do, we are capable of staying within these limits imposed by the order of the world upon our actions.

Such words as the Captain’s have been used by human beings to justify to themselves and to others the reasons for their actions from the committing of petty crimes to genocides. They see their crimes as performing a duty, just “following orders”, or as Adolf Eichmann said: “I was just a scheduler of trains; I didn’t kill anybody”, or as Elon Musk in his destruction of USAID does not see himself as responsible for the possible deaths of 15,000,000 human beings. It is indicative of a loss of a sense of ‘otherness’. It is the Ring of Gyges: the invisibility and anonymity we seek in order to dispel any responsibility for our actions. We allow this committing of crimes to ourselves when it is accompanied by an increase in our ‘good fortunes’.

The root of all crimes is, perhaps, the desire for social prestige whether that is achieved through position, money or recognition. The root of all sin is the denial of the light, the denial of truth, the denial of what is the essence of our humanity. This denial results in our becoming increasingly inhumane and cruel. For the Captain, it is Edmund who will determine what ‘happy’ will become for him by his giving to the Captain ‘noble fortunes’; and the Captain believes it. He does not see his act as “inhumane” but calls it “man’s work”. He will achieve his noble fortunes through the committing of an ignoble act, a heinous act.

One would need to look far across the breadth and depth of English literature to find two more contrasting views of humanity in a work than that which is presented here in these two brief scenes from King Lear. Human beings are capable and culpable of both forms of action: we have an infinite capacity for Love and forgiveness as well as a finite capacity for committing the most heinous crimes; only Love is both beyond and within the circle or sphere, and all human action is done within the sphere (or the realm of Necessity). At bottom, all sin is the sin against the light, or truth.

Contemplation and Calculative Thinking: Living in the Technological World

The passages from King Lear give us an entry to understanding a practical alternative way of being-in-the-world to the current conditioning or ‘hard-wiring’ of our way of being under the technological world-view operating as it does within the principle of reason. This alternative way involves contemplative thinking as opposed to calculative thinking. This contemplative thinking is open to all human beings: it is not a special mental activity. It is an attitude toward things as a whole and a general way of being in the world. It is the attitude that Lear proposes for himself and Cordelia on how they will spend their time in prison: while they will still be in the world, they will not be of the world. While they will be involved with the “poor rogues” and “gilded butterflies”, the world of those rogues and butterflies will not be their world.

What does this mean for us? It suggests that we are in the technological world, but not of this technological world; we are here in body but not in spirit. This is not a Ludditian rejection of technology. We are free in our relation to technology. We avail ourselves of technological things but we place our hearts and souls elsewhere. This detachment involves both a “being-in” and a “withdrawal-from”. Like Lear and Cordelia, we let the things of the technological world go by, but we also let them go on. Like Lear and Cordelia, the detachment is both a “no” to the social and its machinations, but it is also a “yes” to it in that it lets that world go on in their entertaining of it.

What is Calculative Thinking?

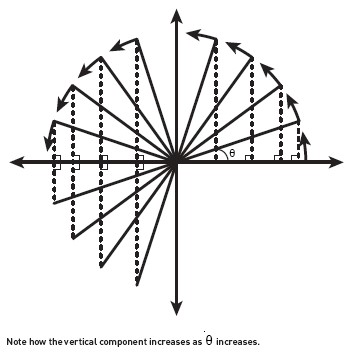

The illustrated gyres on the left are an example of our ‘projections’ of our understanding of our being-in-the-world. These projections are a product of Eros expressed as ‘need’. Being is the essence of technology: Eros as time adapts itself to the Logos as “form” (space) and is thus able to “inform” and to be of use in the meeting of those ‘needs’ that are the projections of Eros.

Calculative thinking is how we plan, research, organize, operate and act within our everyday world. This thinking is interested in results and it views things and people as means to an end. It is a viewing that sees human beings as “human resources” or “human capital”. It is our everyday practical attitude towards things. Contemplative thinking is detached from ordinary practical interests. From where does calculative thinking originate?

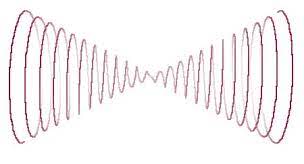

Calculative thinking is illustrated by the spirals or gyres illustrated above. From the centre of the sphere that is our site in our being-in-the-world, we send out or ‘project’ what plans, research, activities we are involved in and these create a world that is itself sphere-shaped. These plans and activities are ‘echoed’ back to us. It is the logos as language and enumeration (mathematics) which establishes those spheres that are the worlds of our experience. These spheres are the worlds of the ‘poor rogues’ and ‘gilded butterflies’ whom Lear and Cordelia will entertain. These spheres are sometimes called “bubbles” today, and various types of human beings may occupy and share the same bubble or sphere or part of a bubble or sphere much like in a Venn diagram. We speak of a “sphere of influence” that we attribute to the powers of various individual human beings. This is the projection that they have over and into the spheres that are projected by others. We measure our freedom by how much of our sphere is truly in our possession and not under the influence of powerful people. The amount of this freedom is determined by the self-knowledge that we may have at any given time.

It is language and enumeration that are the metaxu or media that establish our relation to everything that is and to everything that is not. It is language, with the assistance of eros, which entraps us into seeing presence and the things that presence as “data” and this “data” must then be transformed into a “form” so that it may “inform” and thus become a “resource”. This is why our age is called the Information Age.

The piety that is religion establishes what should be looked up to and what should be bowed down to. Aristotle called or implied that human beings are ‘the religious animal’ in his discussions of piety in both his Politics and his Nichomachean Ethics. In other days, this piety was indicated by that object or site which held the highest point and dominated one’s view. In the West, the highest point was dominated by the spire of the cathedral or the minarets of the mosque from which the imam made his call to prayer. These indicated the way of being of the individuals who lived within those communities. In the East, it was the statue or temple of the Buddha, or it was in the prohibition that no human construction was to be higher than the highest coconut tree within the sphere of site of a Balinese person. These are now not the most dominant points. The most dominant points are the communications towers that are the logistics and infrastructure of our Information Age and these are global in influence.

“Information” develops into the setting in order of everything that presences as “data”, and information establishes itself in the “resources” that result, and rules as “resource” itself. This is the essence of artificial intelligence and it is the danger of artificial intelligence. The algorithm rules and determines the understanding and thinking of the spheres of the individuals whose spheres have been created from that algorithm which are made manifest in their projections. While living within the world of technology, human beings are physically, mentally and spiritually changed by that technology.

The danger of the tyranny embedded in technology is obvious: the creators of the algorithm will determine the understanding and thinking as well as the actions of those who are subject to the algorithm. They are the new sophists who use rhetoric as their meta-language. They will pre-determine their spheres and thus their actions. This is the essence of cybernetics, the unlimited mastery of human beings by other human beings. Cybernetics provides a framework, a form which determines the principles of communication (the form that informs and how it informs, similar to the rhetoric of the sophists of ancient days), the control, and the feedback (the algorithm). Cybernetics determines future actions. The term cybernetics originates from the Greek word “kybernētuēs,” meaning “steersman” or “governor”. Cybernetics is political. It deals with the control of the many. One should be reminded of the many analogies Plato makes in his dialogues with regard to ‘the steersman’ or the ‘helmsman’. Cybernetics is the technology of the helmsman or steersman.

What we choose to be in our doings in the worlds of our projections is that which demonstrates our skills, aptitudes, and fitness to bring forth the “work” that is the product or produce of that world be it goods, services or ideas. We feel ‘at home’ in these worlds. This ‘at home-ness’ is what is understood as ‘justice’; our being in those worlds is something we are ‘fitted for’, what is suitable for us. The ‘unbalanced soul’ driven by the desire for power or prestige will seek to occupy all of the space (logos) within the world that the sphere represents. These are those who do not have the skills, aptitude or fitness (the techne) for a world that they have become involved in and so they must use deceit, machinations and lies. Their product will be injustice.

Human beings come to presence as the ‘perfect imperfection’ dominated by Eros as need (Time). In the perduring of their presence, they are the zoon logon echon. Their perdurance is in language (logos): word and enumeration. In their perdurance, human beings adapt and change, but these adaptations and changes are appearances only. They are ‘surface phenomenon’ and are subject to evil, the denial of the good and the denial of the light. The coming to presence of the ‘form’ that ‘informs’ is the algorithm that is the principle of reason. The principle of reason is a principle of Being: it is Eros present as ‘need’ and shows one of his faces.

“Stupidity” is a moral phenomenon, not an intellectual phenomenon. “Intentional ignorance” is the giving over of responsibility for one’s actions, much like the story in the ring of Gyges. There is a parallel between invisibility and anonymity, and this invisibility shows itself in the inability of the individual who believes in the “invisibility” of their anonymity to think or relate to the consequences of their actions. Moral decay and depravity, the lack of self-knowledge that involves the uncertainty of what it means “to be a man”, what is “male excellence”, are all results of the failure to live within the essence of being human by revealing truth. These make the individual less “humane”. These social phenomenon are all connected and rooted in the sin against the light: the failure to bring things to light and the denial of the light.

The essence of technology which presents itself in the appearance of information correspondingly changes the essence of human being by closing down those open regions that are possibilities of freedom for human beings both in thought and action. The various worlds of human beings become closed down because they are limited in possibilities, and reality becomes replaced by fantasy, an empty, unthoughtful wishing that constructs “virtual” worlds. These virtual worlds are essentially nihilistic in nature and mirror the worlds of the rhetoricians and sophists from ancient days. The virtual worlds are the outer reaches of the gyre that has been projected from the central position of the self. The aspirations of those who wish to colonize Mars, for instance, are an example of this nihilism in action. These fantasy worlds are a diminution of the temporal and spatial limitations of necessity or reality, and they accentuate the immediate, the gut reaction. This places the viewer/hearer in the center of the action or the sphere. In the Aristotelian context, pathos or emotion discourages critical analysis fostering an immediacy that endures long enough to inspire one to action (or simply to purchase a product). This is the opposite of Aristotelian phronesis.

The ‘tech bros’ and ‘cybernauts’ are those who have lost all sense of ‘otherness’ and who have come to the conclusion that there are some human beings to whom no justice is due for they are merely ‘resources’ and disposables or they are ‘useless’. That technology as information grounded in the principle of reason is Being itself, then technology will never allow itself to be mastered either positively or negatively by human doing alone. Technology cannot be overcome by human beings for that would mean that human beings have overcome Being i.e. immortality. It is from within the Eros and the Logos that we must look for salvation from the way of being that is technology.

One type of calculative thinking is that thinking we call ‘machination’. It does not require computers or calculators and it is not necessarily scientific or sophisticated. It would be better understood in the sense of how we call a person “calculating”. When we say this we do not mean that the person is gifted in mathematics. We mean that the person is designing; he uses others to further his own self-interests. Such a person is not sincere: there is an ulterior motive, a self-interested purpose behind all his actions and relations. He is engaged with others only for what he can get out of them. He is an “operator” and his doings are machinations. His being-in-the-world may be said to rest on the saying attributed to H. L. Mencken: “No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American people.” The ‘calculating’ person seeks empowerment or an increase in the influence of his sphere that has intersected the spheres of others.

Calculative thinking is, then, more of a general outlook on things, a disposition, a ‘way of life’. It is an attitude and approach that the things are there for what we can get out of them. People and things are there for us to exploit. This general outlook is determined by the disclosive looking of technology, how it reveals truth, and its impositional attitude towards things. The transforming of the world that is, our reality, into ‘data’ kills both eros and logos and creates a sterile, homogeneous world from which we flee into the realm of ‘virtual worlds’ which, too, are a product of that same limited imagination that constructed the understanding of that reality that is always before one. Calculative thinking inevitably requires moral obtuseness.

There is no lack of calculative thinking in our world today: never has there been so much planning, so much problem-solving, so much research, so many machinations. TOK itself is a branch and flowering of this calculative thinking. Indeed, what is called critical thinking is but another example of the calculative thinking found in other areas of what is called thinking. But in this calculative thought, human beings are in flight from thinking. The thinking that we are in flight from is contemplative thinking, the essence of which is to reveal truth, the very essence of our being human and the way in which we engage in our ‘humanity’. In this flight, we are very much like Oedipus who, after hearing the omen from the oracle at Delphi and its prophecy, rashly flees in the hope that he can escape his destiny. As with Oedipus we, too, are blind and unable to see in our flight from thinking and in our rash attempts to “change the world”.

What is Contemplative Thinking:

Contemplative thinking, on the other hand, is the attention to what is closest to us. It pays attention to the meaning of things, the significance of things, the essence of things. It does not have a practical interest and does not view things as a means to an end but, much like Lear and Cordelia, dwells on the things for the sake of disclosing what makes them be what they are. It is an engagement which is a disengagement.

Contemplative thinking allows us to take upon ourselves “the mystery of things”, to be “God’s spies” in the two-way “theoretical looking” of Being upon us and of ourselves upon Being. To be “God’s spies” we must remove our own seeing and our own looking, that looking and seeing that we have inherited as our “shared knowledge”, our “perspectivism”, and allow Being to look through us. This seeing and looking through is not a redemption that is easily achieved or bought. The pain-filled ascent in the release from the enchainment within the Cave to the freedom outside of the Cave or Lear’s suffering and de-struction on the heath in the storm are indications of the kinds of exertions that are required. King Lear in his anagnorisis has arrived at the truth of what it means to be, as such, and of his place in that Being. Contemplative thinking is a paying attention to what makes beings be beings at all, but contemplative thinking is not a redemption which can be cheaply bought.

The word “con-templation” indicates that activity which is carried out in a “temple”. It is that which is responsible for a communing with the divine. A common word for it is “prayer”. The temple is where those who gather receive messages from the divine. Our ’embodied souls’ are temples. Lear and Cordelia’s prison is, as such, a “temple” to Lear. Within a temple, one receives auguries. An augury is an omen, a being who bears a divine message which must be heard by those to whom it is spoken. In and through this hearing, one is given to see the essence of things and to “give back” those essences to Being.

Contemplation is the observing of beings just as they exist and attending to their essence. It is a reserved, detached mode of disclosing that expresses itself in gratitude, the giving of thanks: we give thanks to Being for being. This attention is available to all human beings who through their love, like Lear and Cordelia, are open to the otherness of beings without viewing those beings as serving any other purpose than their own being. For human beings, it is the highest form of action directed by what the essence of human being is, the revealing of truth through the logos. It is arete or virtue, what we understand as ‘human excellence’. As the highest form of human being itself, it must be available to all since it is our very nature as human beings. It is the height of what the Greeks called arete “virtue”, “human excellence” and signifies the height of being human.