A few notes of warning and guidance before we begin:

The TOK essay provides you with an opportunity to become engaged in thinking and reflection. What are outlined below are strategies and suggestions, questions and possible responses only, for deconstructing the TOK titles as they have been given. They should be used alongside and along with the discussions that you will carry out with your peers and teachers during the process of constructing your essay.

The notes here are intended to guide you towards a thoughtful, personal response to the prescribed titles posed. They are not to be considered as the answer and they should only be used to help provide you with another perspective to the ones given to you in the titles and from your own TOK class discussions. You need to remember that most of your examiners have been educated in the logical positivist schools of Anglo-America and this education pre-determines their predilection to view the world as they do and to understand the concepts as they do. The TOK course itself is a product of this logical positivism.

There is no substitute for your own personal thought and reflection, and these notes are not intended as a cut and paste substitute to the hard work that thinking requires. Some of the comments on one title may be useful to you in the approach you are taking in the title that you have personally chosen, so it may be useful to read all the comments and give them some reflection.

My experience has been that candidates whose examples match those to be found on TOK “help” sites (and this is another of those TOK help sites) struggle to demonstrate a mastery of the knowledge claims and knowledge questions contained in the examples. The best essays carry a trace of a struggle that is the journey on the path to thinking. Many examiners state that in the very best essays they read, they can visualize the individual who has thought through them sitting opposite to them. To reflect this struggle in your essay is your goal.

Remember to include sufficient TOK content in your essay. When you have completed your essay, ask yourself if it could have been written by someone who had not participated in the TOK course (such as Chat GPI, for instance). If the answer to that question is “yes”, then you do not have sufficient TOK content in your essay. Personal and shared knowledge, the knowledge framework, the ways of knowing and the areas of knowledge are terms that will be useful to you in your discussions.

Here is a link to a PowerPoint that contains recommendations and a flow chart outlining the steps to writing a TOK essay. Some of you may need to get your network administrator to make a few tweaks in order for you to access it. Comments, observations and discussions are most welcome. Contact me at butler.rick1952@gmail.com or directly through this website.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B-8nWwYRUyV6bDdXZ01POFFqVlU

A sine qua non: the opinions expressed here are entirely my own and do not represent any organization or collective of any kind. Now to business…

The Titles

1. Do historians and human scientists have an ethical obligation to follow the directive: “do not ignore contradictory evidence”? Discuss with reference to history and the human sciences.

Title #1 asks us to discuss whether there are any “ethical obligations” in our study or research of human history (presumably, would we lie about the history of rocks?) and the human sciences, and whether or not these ‘ethical obligations’ involve the consideration of ‘contradictory evidence’ that might arise during that research. It asks the question: what are the ethics of the world of academic research? The title implies that ‘contradictory evidence’ can be, and is, overlooked in many cases in the worlds of the human sciences and history.

The ‘ethical worlds’ of history and the human sciences are shaped by the ‘moral principles’ the individual researchers happen to have. Morals are universals; ethics are particulars. Morals are universal principles based upon a distinction between good and bad (good and evil, if you will) which determine the essence (the ‘whatness’) of the particulars that are the ‘ethical obligations’ or the principles of actions that human beings take in their living within communities by establishing a hierarchy of from bad to good, from worst to best. Morals are of the world; ethics are of the many ‘worlds’ that we as human beings participate in. Morals point to a perfection that human beings in their actions attempt to attain. They are the ‘virtues’ that comprise ‘human excellence’.

In your TOK essay here, you are asked to look at contradictory evidence to the thesis that you are going to propose on the title that you choose. Is this the IB’s attempt to educate you to be “ethical” while developing your critical thinking skills and your research? Why should you/we be ‘ethical’? What does the ‘ethical’ have to do with research and ‘truth’? and what does ‘truth’ have to do with our being human, with our humanity, with our being-with-others? What is the impact of our being ‘untruthful’ on our humanity and on our being-with-others in communities?

“Ethical obligations” are duties imposed on manners or ways of action, the ‘ways and means’ of action, what someone ‘should’ do in their conduct. They are limitations on ‘freedom’. Here, the action being considered is the conduct of research, how the research is to be carried out, and how it is to be reported. In the carrying out of research, ‘contradictory evidence’ “should” be considered. Notice that I am not using the word “must” here. Is the consideration of contradictory evidence a ‘should’ or a ‘must’ for human beings? Are all human actions considerations of the questions of ‘should’ and ‘must’? Such considerations regarding research and its findings involve questions regarding what the nature of truth is (i.e. what is a ‘fact’) and how truth is related to justice ( to our being with others in communities). They are essentially political questions. Why should we as human beings be concerned about truth, especially if and when it is not convenient for us to have such a concern?

An historian’s or social scientist’s findings are not known until they are written down and given some permanence of some kind, until they are “revealed” through shared discourse. “Truth” is a revealing, an uncovering. Until such a time, the findings are only known to the historian or social scientist. The revealing is through a ‘hearing’: we hear what others have said regarding the nature of something. Such a question as the TOK asks here is to look at the grounds of the ‘viewing’ from which the research is undertaken and the purpose as to why the research is undertaken in the first place. This ‘viewing’ first came from a ‘hearing’. These ‘hearings’ determine the manner in which ‘judgements’ will be made regarding what is under consideration. These judgements determine the interpretation of the facts. If there are contradictions to the judgements then we are ‘ethically’ bound to change the manner of the ‘viewing’. It is not sane to continue on knowing that one will make the same mistake over and over again.

Is there a hierarchy in existence in which the importance of the research matters? In cancer research, for example, the vested interests of the researchers will sometimes cause them to overlook the ‘contradictory evidence’ that may be present in their findings, for the consequences of such evidence may result in a loss of prestige or power or money. The ‘vested interests’ predetermine the judgements and thus the manner of ‘viewing’. Cancer is primarily a ‘white’ disease. The same efforts are not given to the eradication of malaria and other diseases that plague the world’s coloured populations.

‘Contradictory evidence’ questions the ‘viewing’ or hypothesis that has been put forward to account for the thing that is being questioned and so questions the interpretation. It questions the grounds. The ‘viewing’ is not whole. The deeper question being asked is whether or not there is such a thing as ‘objective knowledge’ and what is the nature of this ‘objective knowledge’. Is ‘objective knowledge’ possible? Without the inclusion of contradictory facts or evidence then we can be certain that what is being given to us is not knowledge. It is opinion. Does this matter? If the results ‘work’, do we care? Similar questions should be considered regarding Title #5.

The question asks us to distinguish between propaganda and knowledge, particularly with regard to history and the human sciences. In all cases, it involves our being-with-others. An ‘ethical obligation’ is something that binds or obliges a person to do or not do certain things, often based on duty, law, or custom. Duties, laws and customs are things which societies create and develop through their histories. They are based on opinion. All of the concerns regarding obligations involve our being with others in a particular community at a certain time i.e. they concern other human beings and our relations to them. The duty or obligation may differ from community to community depending on how the value of truth is regarded within that community. A tyrannical regime will regard the value of truth differently than a democratic or oligarchic regime. Uttering the truth in a tyrannical regime can sometimes result in prison time or death.

Are there obligations that are binding on the individual that have no political considerations? Do hermits have ethical and moral obligations? There are many who believe that ‘morals’ are ‘subjective’ i.e. they are ‘values’ belonging to the single individual. Such a statement dismisses the notion of good and evil, good and bad, as nothing other than a ‘subjective value’. After all, ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’, is it not? Such a belief accounts for the lack of a “moral compass” among many of the so-called ‘educated’ and results in moral obtuseness.

Do I have certain obligations that apply to myself only? We are constantly in a battle not to deceive ourselves when it comes to the meaning of the experiences that we have. “Stupidity” is a moral phenomenon that becomes an ‘ethical’ phenomenon when it involves our being with others. It begins with self-deception and then proceeds to the deceiving of others. There is not such a great distinction between morals and ethics as is commonly made out to be. “Stupidity” is not an intellectual phenomenon. The ignoring of contradictory evidence is ‘stupidity’. We ‘owe’ it to ourselves as human beings not to be stupid. It is human nature to reveal truth. We are not fully human if we do not do so.

This ‘owing to ourselves’ implies a state of ‘indebtedness’. To whom or what is the debt owed? Why? This sense of indebtedness is how we conceive justice. If I am a researcher in the human sciences or an historian, I must first have the desire to reveal truth before I can do so. If I am lacking a ‘moral compass’, my desire or goal may be to obfuscate the truth since there are many times when what the truth reveals is inconvenient for me. There are many examples of whistleblowers that can be used to show researchers who have gone against the prevailing powers that be in order to ‘reveal’ the contradictory evidence that their institutions or corporations wished to hide in order to meet the ends that those institutions or corporations had determined which usually involved money or power. In the USA, racists and bigots promote the idea that Haitian immigrants are eating their dogs and cats. The greater bestiality is in the perpetrator of the lie.

In the arts, do the consequences of contradictory evidence have a significant impact on the community? When critics make judgements regarding the latest film and we find the film not entertaining, are there any consequences involved? Artistic views are simply a matter of taste since art is only concerned with our ‘entertainment’, is it not?

In medicine, on the other hand, the consequences can be quite serious. Nowadays, the purpose of the arts is to entertain. They either do so or they do not. All art is ethical at some point since all art involves an audience of some kind. In the human sciences and medicine, consequences arising from not giving contradictory evidence sufficient attention can be devastating. Think of the opioid crisis as an example. Are there examples of bad works of art killing anyone? (Propaganda, for example?) There are many examples of ‘falsehoods’ resulting in the deaths of human beings. Certainly “the art of rhetoric” has resulted in the deaths of many human beings, both currently and historically. Many concrete examples of such cases can be found. In the USA, the “January 6th Insurrection” is a possible example of contradictory evidence that is overlooked and the overlooking involves the deaths of other human beings.

“Ethical obligations” are restructured under the political regime that happens to be in power at the time. Fascists feel they have an ‘ethical obligation’ to re-write history because the revision of history is necessary for their empowerment, and power is their ultimate end. As George Orwell correctly observed, he who controls the past controls the future. To do so requires the telling of lies, an obligation to ‘intentional ignorance’ when it comes to history. The algorithms of fascism require an interpretation of things that is ultimately a shadow of their reality (Plato’s allegory of the cave). These algorithms determine the design of the plan which in turn determines how things will be arranged in the hierarchy of true or false and, thus, how things will be understood and viewed and then communicated.

2. Is our most revered knowledge more fragile than we assume it to be? Discuss with reference to the arts and one other area of knowledge.

“Our most revered knowledge” is what we bow down to or what we look up to. We could use the word ‘piety’ to describe our relation to this knowledge. Piety is a way-of-being in the world. It is that which encompasses all our thoughts and actions. For the majority of us in the West, technology is what we bow down to or what we look up to, and our “piety” is our technological way-of-being in the world. Is the knowledge embraced by this piety ‘fragile’?

“To revere” is to respect someone or something deeply. This reverence with regard to knowledge is based on how that knowledge reveals truth for us. If that truth is seen as empowerment, what ‘works’, then that which increases our power, our freedom, is what we revere. Technology ‘frees’ us from nature. Our dominance of nature increases our ‘freedom’ allowing us to change that which we see before us. This ‘freedom’ to change is what is revered.

There are many who ‘revere’ the knowledge that is most useful to us in the name of our freedom. For the ancients, the ‘useful’ was considered the ‘good’ of something. For example, many people hold Elon Musk in high esteem for his discoveries based on the applications of the mathematical sciences that are proving useful to human beings’ activities. These activities usually deal with the expansion of the technological itself or the dealing with problems that technology itself has created.

With the development of useful tools which are used to dominate nature comes a corollary tendency to authoritarianism in political thinking. This reverence, the emanation of empowerment, is based on how we represent technology to ourselves as an array of neutral instruments, invented by human beings and under human control. This is considered a common sense view of technology. But this ‘common sense’ view hides from us the very technology we are attempting to represent to ourselves and undermines our efforts to bring it to light. The coming to be of technology has required changes in what we think is good; what we think the good is, how we conceive sanity and madness, justice and injustice, rationality and irrationality, beauty and ugliness. These changes indicate the ‘fragility’ of that knowledge that we revere.

In the past (and in a few places in the present), it was quite easy to recognize what the “revered knowledge” of a community was. One simply had to look for the highest point of that community. In Canada, the steeples of Roman Catholic churches once dominated the villages of the French-Canadians who dwelt within them as one travelled along the banks of the St. Lawrence River. Today, it is the telecommunications tower that is the highest point in those communities. In Thailand, a statue of the Buddha usually dominated the highest point. Once again, a telecommunications tower will always be found towering over the Buddha in many Thai communities today. Clearly “information”, data and its transfer, is what we hold most dear, and the nature and interpretation of “information” is very fragile. Information and data transfer is the life-blood of technology and of the technological way-of-being in the world. Our piety rests in our reverence for this information transfer and the technology and the tools that accompany that technology.

What we conceive and judge our greatest art to be is that art which reveals the truth of human life at its deepest levels. This unconcealment of the deepest levels of our humanity is what we conceive truth to be as it reveals to us our human nature and humanity. In the biological sciences, we hold Darwin’s theory of evolution to be the height of perception of what we are as a species. In our arts, something greater and deeper than the truth of Darwin is given to us about the nature of our humanity.

All societies are dominated by a particular account of knowledge and this account lies in the relation between a particular aspiration of thought (“ends”) and the effective conditions for its realization (“means”). The paradigm for our account of knowledge is that which finds its archetype in modern physics. Our account is that we reach knowledge when we represent things to ourselves as objects, summonsing them before us so that they give us their reasons. This summonsing of the things of the world is what we call “research”. What we call AI is the ‘whole’ of the results of that summonsing applied to the ‘world’ of that type of knowing. This summonsing requires well-defined procedures which we call ‘research’, and this ‘research’ is embedded in the algorithms which carry out the actions of the research in AI.

The word “information” may be defined from its roots: “-ation” is from the Greek aitia “that which is responsible for” > the “-form” > so that it may “in-form”. It is the manner in which the data is gathered and of how the data is uncovered so that it reveals its truth i.e. the form that the data is in. ‘Research’ is not then something useful for some ways of knowing and not for others. It belongs to what we think the essence of knowledge is for it is the effective condition for the realization of any knowledge.

In history and the arts, the past and the ‘work’ of art are represented as objects in which the procedure is to order the object before us to give us its reasons. The past is represented as an object. The difficulty with history and the arts is that when we represent something to ourselves as an object, only as an object does it have any meaning for us. History and the work of art become ‘dead’ for us. We stand above it as “subject”, the transcending summonsers. We guarantee that the meaning of what is discovered is under us and in a very real way dead for us in the sense that what is summoned cannot teach us anything greater than ourselves. The chemical compounds of Van Gogh’s yellow paint are interesting, but they tell us nothing about the truth of the painting “Sunflowers”.

In the Arts, we wish to separate the techniques of Art from the work of Art itself, just as we wish to separate the tools of technology from the technological itself. Shakespeare himself said “The art itself is nature”. Means and ends are not so easily separable. As Aristotle has shown us, the ends are not separable from the means for the ends determine the means.

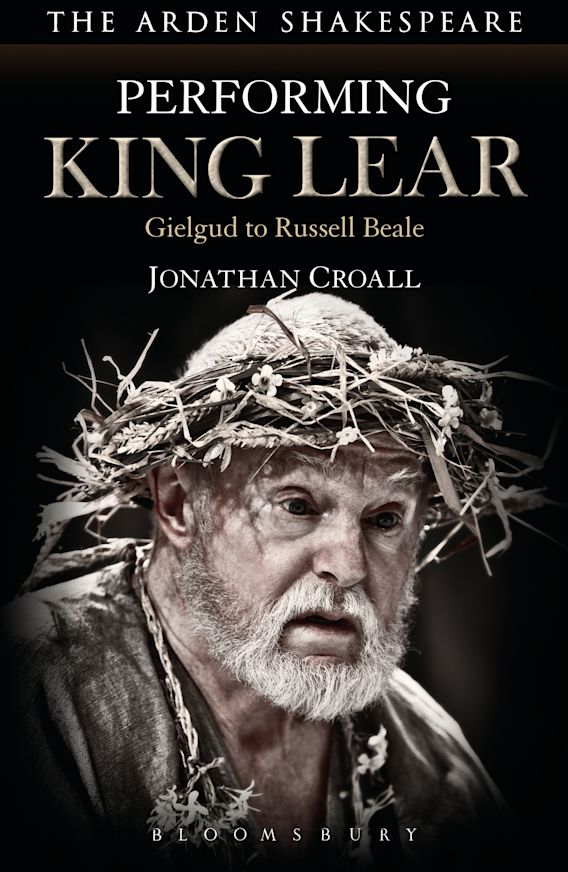

The German philosopher Heidegger has shown that the place experiment plays in the sciences is taken up by a critique of historical sources in the arts. Previous scholarship was a waiting upon the past so that we might find truths which might help us to think and to live in the present. This was why it was once ‘revered’ knowledge. Today, research scholarship in the humanities cannot wait upon the past because it represents the past to itself from a position of its own command. From that position of command you can learn about the past; you cannot learn from the past. The stance of command necessary to research kills the past as teacher. You may watch a performance of King Lear and know all the data that has gone into the production in front of you, but with this knowledge you will not learn anything from the performance in front of you. This is an example of the fragility of our most ‘revered knowledge’: the purpose of the work of art is lost.

3. How can we reconcile the relentless drive to pursue knowledge with the finite resources we have available? Discuss with reference to the natural sciences and one other area of knowledge.

“The relentless drive to pursue knowledge” in today’s world exhibits the sheer ‘will to will’ of a will to power that continues to strive out of the meaningless nihilism of its own making. The questions of “what for?”, “where to?”, and “what then?” are not asked or pondered since the willing itself is all i.e. the ‘relentless drive’. This willing is focused on ‘novelty’, the attempt to bring about the new and the strange.

“To reconcile” means to restore to friendship or harmony. The “pursuit of knowledge” is our desire to turn the world into “resource” so that we may be able to commandeer those resources to our ends. How are we and nature to be ‘reconciled’? To reconcile this relentless “erotic” drive, our need to pursue knowledge, what forms will the pursuit of this knowledge take? Since the Renaissance, our pursuit has been to change the world to realize the goals that we have set for ourselves as human beings. We have placed ourselves at the centre of the world and have summoned the world to give us its reasons. The remarkable achievements of this summonsing make us reluctant to reconcile ourselves to nature. Climate change is nature’s attempt to fight back at this one-sided view of things.

Another meaning of ‘to reconcile’ is to ‘settle, resolve’, to ‘reconcile differences’. How are we to reconcile the differences between subject/object that is the foundation of our stance in the natural sciences? Is there any desire to do so? The incongruities of any possible reconciliation are political questions: how will the finite resources be allotted and who will get to eat what? Examples from history will help to clarify how these questions have been answered by different political regimes.

If “knowledge” is the finished product that we make through the process of our commandeering the world as resource, we can see this ‘relentless drive’ as the making of the total technological world, the turning of the world of becoming into being. This knowing and making has been called ‘absolute knowledge’ by the philosophers. Technology is the highest form of will to power and empowerment. In this stance, there can be no reconciliation.

“Self-knowledge”, a prerequisite for knowing, appears in the form of ‘wise-uppedness’ today, a cynical ‘know-it-all’ attitude that really knows nothing. 54% of Americans cannot read prose beyond the Grade 5 level according to a 2020 report from its Department of Education , while at the same time countless billions of dollars are spent on conquering space as it is seen as the ultimate site of the warfare of the future. In our arts, ‘novelty’ in the outcomes of the production of a ‘work’ is exalted above all other forms of knowledge (the ‘work’ being what we understand as ‘knowledge’) calling itself ‘creativity’. This ‘novelty’ as ‘creativity’ is part of the ‘knowing’ (techniques) and ‘making’ (the work) that is technology.

Our will to power shows itself in our ‘need’ to dominate and commandeer the world conceived as ‘object’, the world conceived as ‘resource’. The world is a ‘finite resource’. The ‘drive to pursue knowledge’ is what we understand as our eroticism at its deepest level: the “need” to have something to will, to domineer, and to consume. The rich are willing to pay exorbitant sums of money to own a work of art that rightly belongs in the “public domain”. Such a desire for the private “consumption” of beauty is what is meant by eroticism. This is what the myth of the Fall out of Paradise is all about.

Modern science is ‘technological’ because in the modern paradigm, nature is conceived at one and the same time as algebraically understood necessity and as ‘resource’. This algebraic understanding is the root of the algorithms of artificial intelligence. Anything apprehended as ‘resource’ cannot be apprehended as beautiful. I objected quite strongly when my principal (a most well-meaning man) referred to his staff, my neighbours and colleagues, as ‘human capital’. This is just another name for ‘human resources’ and for the viewing of the human beings around you as ‘resources’ that can be commandeered and directed. One can see what has been lost and found in our modern conception of the world through the unthought use of these terms.

As is the case with Titles #1 and #2, Titles #3 and #4 are similar in nature. The ‘finite resources’ are the costs of the ‘tools’ and ‘equipment’ necessary to carry out “research” and the reconstruction of the world. This is seen most clearly in our astrophysics and our health sciences. Because we have such advanced tools and equipment in the areas of health, unnecessary uses of that equipment are impelled on those who possess them in order to cover the costs of the equipment. The equipment must be put to use. This is analogous to the bitcoin and crypto-currency rage at the moment.

Liberal arts programs are being cut back because of their costs in many parts of the world. Truth is “expensive”, especially the conveying of truth into the public discourse. The costs of carrying out research in the sciences (the pursuit of knowledge from title #2) are exorbitant; they need to be met by outcomes that will eventually cover their costs (the exorbitant profits of the drug makers that result from the drugs that are produced). The cost of pharmaceutical products is a concrete example of this. ‘The man of peace’, Elon Musk, is the richest man in the world because his discoveries using algebraic calculation aid in the logistics for the future conduct of war. Musk believes that he is in control of his discoveries, but his ‘common sense’ view of technology does not grasp the nature of the reality of technology itself (see Title #2). In a very real and deep way, Musk’s “thinking” is not thinking, in the same way that ‘artificial intelligence’ is not ‘intelligence’ as the ancients understood this term. What kinds of thinking are required to reconcile these differences?

4. Do the ever-improving tools of an area of knowledge always result in improved knowledge? Discuss with reference to two areas of knowledge.

Title #4 directs us to think about what we call “knowledge” and whether or not knowledge can be improved or is improved through the use of better tools. Our understanding of what tools and equipment are arises out of an understanding and interpretation of our world, and refers to our world as the “ready-to-hand”, that world which has become ‘objectified’ and made to stand as ‘resource’. Different equipment and tools belong to the different ‘worlds’ that human beings have created. This bringing to a stand as resource in those worlds is the end result of what we have called ‘research’ in this writing. The key tool of ‘research’ in the modern is the computer, and the apogee of ‘research’ is artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence will direct and determine the science of cybernetics, “the technology of the helmsman”. Artificial intelligence as the science of the ‘steersman’ will come to be present in all other sciences.

What is meant here is that the objective arts and sciences come more and more to be unified around the planning and control of human activities within the human sciences. Technology is the pervasive mode of being in our political and social lives, our being-in-the-world and our being in our various ‘worlds’. With the attempt to dominate the logos (language, the word) through the meta-language that is artificial intelligence comes the corollary dehumanization of our being-in-the-world and an inevitable coming forth of tyranny. The future tyranny will be a ‘happy’ tyranny because there will be no thought capable of coming-to-presence to question it. A sign of this is that with the increasing development and sophistication of communication tools, human discourse (or what I refer to as dialectic in other writings on this blog, the conversations between two or three) is weakened and rhetoric (the language of the one thrown to a many) as a means of communication comes to dominate.

“Knowledge” indicates something that has been brought to light, revealed, unconcealed. It is the ‘truth’ of the essence of the thing. That which has been ‘pro-duced’ or brought forth by our making is ‘knowledge’ and we know more about the things we have made than those things which we have not made. We know more about IPhones, for instance, than about the lilies of the field because we have made the IPhone and (as of yet) not made the lily. One of the goals of the bio-sciences is to make the lily as well as other life forms. The things we have made have been ‘brought forth’ or ‘brought forward’ from out of something else and it is in their making that they are known to us, whereas the things from which they have been brought forth remain in the shadows for us.

In our common sense understanding of “improved knowledge”, there is no question that the greater sophistication of our tools and equipment brings to light, ‘reveals’, ‘unconceals’ the historical facts and artefacts of archeology and history with greater clarity. But notice that what we call “knowledge” is associated with “truth”. The revealing and unconcealing of things requires a hierarchy, for there are different levels at which things may be revealed. In the allegory of Plato’s cave, for instance, the firelight of the artisans and technicians reveals the ‘shadows’ of the artefacts of those things which they themselves have made and casts these shadows on the cave’s walls. We know more about the things which we have made than of those things which we have not made. The cave itself is Nature, the cosmos. What is revealed are images, not the reality of the cave itself for the light of the sun is dimly seen. The allegory of the cave is an image of the truth of things and how this truth is revealed.

Today, the widening gyre of technological innovation and novelty is focused upon solving many of the problems that technology itself has created. The internal combustion engine of the automobile will eventually be replaced by the electric vehicle. The rare metals required for the batteries’ construction, the weight of the batteries themselves, etc. are problems that have, as of yet, not been properly thought through in relation to the pollution they will cause, the energy that they will consume in their making, etc. This is but one example of the issues faced when thinking about ‘improvements’ in technological innovation.

5. To what extent do you agree with the claim “all models are wrong, but some are useful” (attributed to George Box)? Discuss with reference to mathematics and one other area of knowledge.

Models are products or the ‘works’ of hypotheses and speculations; that is, they are the products of opinions. They are images; creations of the imagination. Because they are the products of opinion, they may be either true or false; they may be right or wrong. To say that “all models are wrong” is an example of hyperbole. Some models ‘work’ and some do not. The “usefulness” or utility of a model, whether it works or not, is how we judge its “trueness” and its “goodness”: this “truth” is related to its “correctness”, and the “correctness” in this essay title is related to the phrase “to what extent”. When we ask about the “extent” of something, we are asking a mathematical question which will be answered by way of statistics which will be arrived at by calculation. The calculations will be gathered through research. A statistical nexus is a metaphor; it conveys the degree of “truth” that may be contained in a statement or assertion. It relies on the “calculability” of the thing. A model, too, is a metaphor.

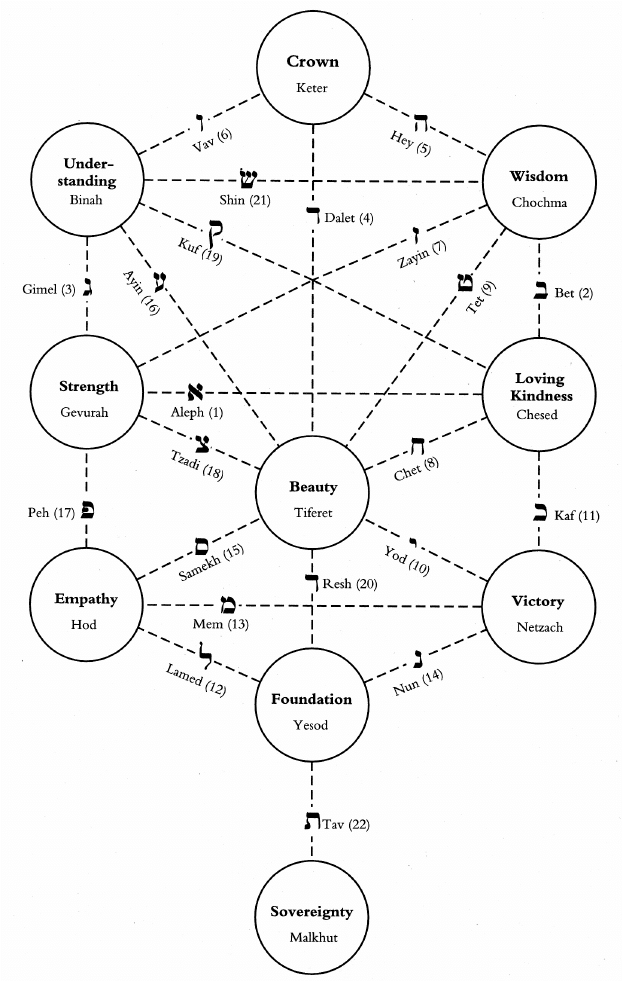

In mathematics, an axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement (logos) that is taken to be true prima facie, “on its face” or its ‘outward appearance’. It is the arche or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word ἀξίωμα (axíōma), meaning ‘that which is thought worthy or fit’ or ‘that which commends itself as evident’. “Mathematics” for the Ancient Greeks was “that which can be learned and that which can be taught”. What can be learned and what can be taught is that which is present (ousia) or “what shows itself” to us. What shows itself to us is its ‘face’. It is that which ‘commends itself as evident’.

The truth or falsity of an assertion, which is a statement (logos), was to be found in its ‘fittedness’ or ‘worthiness’. The ‘fittedness’ of something was based on a judgement of the thing: “Yup, these are a good pair of shoes” is a judgement based on a statement of the ‘aptness’ or ‘fittedness’ of the thing to its use. Its ‘fittedness’ was its ‘goodness’. Because they were ‘fit’ for the purposes of what shoes are supposed to do, the shoes were ‘good’. The ‘worthiness’ of the thing was the thing’s ‘value’ or ‘suitability’ related to its intended use. Some shoes are better or more worthy than other shoes and are more expensive. The ‘worthiness’ of a thoroughbred racehorse was in its ability to run fast. It was not ‘worthy’ if it could not. The worthiness of a good meal was the pleasure of its deliciousness and the satisfaction of the hunger of the individual enjoying it. If the meal is not delicious, it is not ‘good’. The ‘worthiness’ of a human being was to live well in communities and to be open to the whole of things. It is this last statement which is gravely under threat at the present time.

Today, the goodness or ‘value’ to be found in a work of art is related to its ‘entertainment’ value, how delightfully it occupies our attention in the present. This is quite different from ancient idea that a ‘work’ of art was meant to be an object of contemplation and reflection so that we might learn from it what was ‘useful’ for our living in the present. Works of art provided the models, the ideals, that the civilization was based on. Think of Achilles and Ulysses in Ancient Greece, Caesar in Rome, Moses in Judaism, Christ and Mary in Christianity, Mohammed in Islam (even though representations of Mohammed are forbidden in Islam. Why?), Michelangelo’s “David” in the Renaissance. What modern figure do we have as a model upon which our civilization can be based? The artists themselves? What ‘fittedness’ applies to modern models in the Arts today?

The confusion over our use of models in the arts is the result of our confusion over the place of morals and ethics in our day-to-day activities. When one looks at discussions regarding ‘designer babies’, the eugenics which will be possible with our discoveries in the biological sciences, Einstein and Mozart are two names mentioned as possible models for these new human beings. The choices clearly indicate that the technological is what we bow down to and what we look up to, the knowing and making of the arts and the sciences. One does not hear the name of Mother Teresa mentioned in these aspirations. Does the world need more Einsteins and Mozarts or more Mother Teresas?

In the West with the arrival of the new sciences, many Christians felt that Roman Catholics were “pagans” in their appearance to worship the idols and icons of Christ and Mary that had been produced by the artists of their times. This “error” in seeing of these critics indicated that a changed vision had arrived over what thinking was and how thinking was to be seen as distinct from what contemplation, prayer and attention were. While the prayer to the realities represented by the icons or images of the statues was that contemplation that looked for guidance and grace as to what to do in one’s daily life, the literal rational thinking of those who changed the view and understanding of what reality was was beginning to dominate what was to be understood as rationality and thought. The models used for an understanding of what human excellence is underwent a great transformation at that point in time in the history of the West.

6. Does acquiring knowledge destroy our sense of wonder? Discuss with reference to two areas of knowledge.

A “sense of wonder” is a pre-requisite and a necessity for thought and thinking. It is “wonder” that gives rise to thought, which begins with the asking of questions. “Wonder” begins with the sense of mystery that arises from our being-in-the-world. In the English language, wonder is associated with the ‘new’. The ‘new’ is that which is strange and unfamiliar. Does the “wise-uppedness” of many today with regard to the ‘new’ and the ‘novel’ indicate a condition of modern democratic nihilism and thus the destruction of the sense of wonder? What sense of wonder do we have regarding the ‘novelty’ of that world which is all around us? What is the ‘novelty’ of our technological society and what does it portend for our future?

The dominance of ‘novelty’ shuts down “wonder”. The achievements of the modern project in science and medicine are a source of wonder. The world as object has given its reasons as it has been summonsed to do. All of us in our everyday lives are so taken up with certain practical achievements in medicine, in production, in the making of human beings and in the making of war, that we are forgetful of the wonder necessary for the realization of what has been achieved. What is referred to as AI, artificial intelligence, is the apogee of that achievement. AI should and must instill in us a great sense of wonder.

The word ‘novelty’ as a non-countable noun means “the quality of being new, different and interesting”. As a countable noun, novelty means “a thing, person or situation that is interesting because it is new, unusual or has not been known before”. At the same time, a ‘novelty’ is a small cheap object sold as a toy or a decoration. How do we reconcile these opposing meanings of the word? The word itself seems to contain a sense of our being over-satiated by the sheer volume of the novelty that is all about us. We are further from knowledge the more we are overwhelmed with “information” and with the ‘novelty’ of our ‘making’ in our technological way-of-being in the world. If one were to do an illustration of Plato’s allegory of the Cave today, one would have to put laptops and handphones in the hands of the prisoners to indicate a level still further removed from the reality of the good and the beautiful.

When we represent technology as an array of instruments (tools and equipment) lying at the free disposal of the species that creates them, this apparently true account of technology prevents us from experiencing the ‘wonder’ of the novelty of the current situation of our being-in-the-world. Defenders of artificial intelligence, for instance, will make statements such as “artificial intelligence does not impose on us the ways it should be used”, and statements such as these are made by people who are aware that artificial intelligence can be used for purposes which they do not approve, for example, the tyrannous control of human beings. Elon Musk is a primary exponent of such a view.

The ‘should’ of such a statement goes beyond the knowledge of those who are involved in the making of artificial intelligence and of the machines and computers that will drive it. These discussions of artificial intelligence separate means and ends. The “ends” are within the making of the artificial intelligence itself. Because Musk and others like him are aware of the possible good and evil purposes for which artificial intelligence can be used, he and others like him express what artificial intelligence is in a way that goes beyond its technical description: “It is an instrument made by human skill for the purpose of achieving certain human goals. It is a neutral instrument in the sense that the morality of the goals for which artificial intelligence will be used is determined outside of the artificial intelligence itself.”

All of us are aware of the myths of Frankenstein in one form or another. These imaginary myths are part of our sense of wonder. All tools and instruments can be used for bad purposes; and the more complex the capacities of the instrument, the more complex can be its possible bad uses. Artificial intelligence has an infinite potential for both good and evil. The danger involving artificial intelligence is that while we may think that it is a neutral instrument or tool in a long line of neutral instruments and tools which we in our freedom are called upon to control, the liberation of that control to the machine itself means that we are not in a position to rationally come to terms with the potential dangers which this instrument imposes on us. (Think of the examples of Musk’s long line of misadventures with his self-driven cars.)

“A sense of wonder” should be piqued in us when we consider the existence of artificial intelligence and the events which have made its existence possible. Artificial intelligence has been made within the new modern science and its mathematics. This science is a particular paradigm of knowledge that involves the principle of reason (“nothing is without reason”) used to gain ‘objective’ knowledge; and modern reason is the summonsing of anything before a subject and putting it to the question so that it gives us its reasons for being the way it is as an object. With artificial intelligence, we ourselves are the objects of that summonsing. And this should give us cause to wonder…The adjacent emotion to “wonder” is fear and a sense of awe at the ‘terrible’.

From the Online Etymological Dictionary we are informed that the word “monster” is from “early 14c., monstre, “malformed animal or human, creature afflicted with a birth defect,” from Old French monstre, mostre “monster, monstrosity” (12c.), and directly from Latin monstrum “divine omen (especially one indicating misfortune), portent, sign; abnormal shape; monster, monstrosity,” figuratively “repulsive character, object of dread, awful deed, abomination,” a derivative of monere “to remind, bring to (one’s) recollection, tell (of); admonish, advise, warn, instruct, teach,” from moneie- “to make think of, remind,” suffixed (causative) form of root men- (1) “to think.” A “monster” instills a sense of fear and wonder in us, a warning to us to think and to recollect. The advent of artificial intelligence should make us think, ‘wonder’, but the continuous ‘novelty’ that artificial intelligence inspires prevents such wondering and thought.

Because artificial intelligence uses the false logos of the meta-language which is based on the primordial approach to the world as object (“rationality” understood as the principle of reason where “number” as calculus is prior to “word”) and the “reserve” of the stored information that has been gathered through “research”, the particularities of the objects that are the stored information of AI is abstracted so that they may be classified. “Information” is about objects and comes forth as part of that science which summons objects to give us their reasons. This requires classification.

This requirement for reasons and the classification of objects when directed towards human beings impacts how we will come to understand justice in the future. To relate what is being said here to the Human Sciences of politics and economics: AI can only exist in societies where there are large corporate institutions. AI will exclude certain forms of community and discourse and permit others. The portends for the future, the “monster” that is AI, indicate that AI will require authoritarian, tyrannous regimes where human activities will be dictated by a centralized controlling power. As “wonder” showing itself as questioning and thought will not be present, such dictatorial ruling will be a ‘happy’ tyranny to those who are subject to it. At the present time, we are ‘happily’ giving over our privacy and our freedom.

In the Human Sciences, the questions concerning justice which will arise within the summonsing will be determined within three dominant political regimes: capitalist liberalism, communist Marxism, and national socialist historicism. The account of reason outlined here is that the reason which produced the technologies also produced the accounts of justice given in these modern political philosophies. Our accounts of society came forth from the same account of reason and reasoning that brought forth technology and the technological with AI as its apogee. Our entanglement within this complex nexus should bring forth ‘wonder’: ‘what for?’, ‘where to?’, ‘what then?’. AI and the standards of justice are bound together, both belonging to the same destiny of modern reason understood and realized as AI.

AI is the technology of the helmsman, cybernetics, the unlimited mastery of the mass of human beings by the few. AI will ultimately control human activities gathering them so that they are focused on itself and on the making of the fully technological world. This mastery will be freely given over to the few if the desire for freedom and the wonder of a sense of ‘otherness’ is not present in human beings.