“Spiritedness” and Human Excellence

Eros is the “procreator” of “true virtue”, and true virtue comprises courage, moderation, wise judgement and justice. It was believed that these qualities were the ‘highest’ that a human being could attain and comprised human excellence, the ideal, the model, the paradigm. It was believed that these qualities could be attained through eros as Love. Each of the speakers of the Symposium addresses these four virtues in some way, and in their logoi reveal themselves as individuals as well as the nature of all human beings to some extent.

In Alcibiades’ speech in Symposium, we have his criticism of the love of the philosopher which he asserts is beyond the human. In this, he is in agreement with Aristophanes. Alcibiades’ intense ‘love’ and ‘passion’ for Socrates is contrasted with Socrates’ dispassionate attitude towards him as a result of Socrates being in love with what Socrates calls the Beautiful rather than the ‘beautiful’ Alcibiades himself. The example of Alcibiades is used as a warning by Plato of the disaster that can result if we do not develop our eros in an appropriate way. But from what and where is this ‘appropriate way’ and how is it to be ‘appropriated’? How are we as ordinary human beings going to achieve the state of not “wanting” the things that we have come to desire and of knowing the difference between what is truly desirable and what is not? How do we develop the way of thinking that discerns this?

Since Eros is described as ‘fullness’ and ‘need’, we may look at Socrates through such a lens. As “Need”, Socrates’ outward appearance is ugly and far from beautiful; he is ‘ugly’ like Silenus, the satyr, according to Alcibiades (203 c; 215 a-b). It is ironic that Socrates puts on make up before he goes to Agathon’s symposium, and we must think about this detail in the drama that we are about to read. This is not the only ‘mask’ that he wears in that drama that he is about to participate in; Diotima is also a mask adopted by Socrates. According to Alcibiades, Socrates is “dirty and barefoot…always sleeping on the ground without blankets” (203 d, 220 b 3-5). He is “poor” and disdains material resources. He is unique and unlike any other human being that Alcibiades has encountered. The outer appearance of the ‘mask’ hides the beauty within that is far more lovelier and this is the beauty that Alcibiades is after.

As “Fullness”, Socrates is a “schemer after the beautiful and the good” as he likes to be around beautiful young men, according to Alcibiades. His military actions at Potidaea and Delium suggest that he is “courageous, impetuous and intense”. (203 d) He is “passionate for wisdom and resourceful in looking for it, philosophizing all his life” since he is ceaselessly reflecting. According to Alcibiades, he is “a clever magician, sorcerer and sophist” since he charms all kinds of people with his words (203 d). Is Alcibiades referring to Socrates’ use of rhetoric or his use of dialectic? Socrates is a “daimonion” man, capable of being an intermediary or a metaxu between the divine and the human for other human beings. Socrates is capable of producing or ‘bringing forth’ true virtue and not the image of it, and this is what attracts Alcibiades to him. Socrates tries to encourage Alcibiades to gain self-knowledge and to care for his soul which in Alcibiades’ case means that he must give up his ‘love’ of the hoi polloi which Alcibiades is unable to do for it is the root of his power, and Alcibiades’ first love is power. According to Alcibiades, Socrates is a “babushka doll” with many hidden layers. Inside one Socrates, one will find another. For Socrates, Alcibiades is possibly a great man who has chosen to remain with his love for the surfaces of things.

The “lower eros” or the “pandemian eros”, the eros common to all, moves human beings to seek for a kind of immortality, an image of immortality, while the “true Eros” leads human beings to seek for a “true immortality”. The “lower eros” also leads human beings to seek for images of immortality rather than the true immortality which Socrates believes is to be found in the Good. Alcibiades is the “democratic man” who leads a dissipated life governed by an unrestrained indulgence of the appetites. The consequences of Alcibiades’ immoderation ultimately lead to his impiety and his failure to lead the Sicilian expedition which ultimately leads to Athens’ downfall in the Peloponnesian War. An undisciplined Eros can lead to the complete loss of all that one ‘loves’ and can lead to consequences far beyond one’s self. This principle is as true today as it was in ancient times.

Who and what an individual is is shown by the leading passion of their lives or their eros. For most of us, this is shown in our “love of one’s own” and in the tasks which we choose to do. Some desire “procreation” in beautiful bodies leaving the “produce” behind as offspring. Others feel the desire for immortal fame and honour in the procreative production of “works” or of deeds or of the enactment of laws.

Poets who produce images of the gods but who have no knowledge (gnosis) of the gods provide the horizons for the lives of the many who live in their “opinions” under the laws enacted by those in power. They live in the service of the Great Beast which Plato outlines in Bk VI of his Republic. Others are individuals who are destroyed by their passions giving us the essence of tragedy as will be the case with many of the participants in the drama that is the Symposium. At the time the drama of the Symposium is retold to us through Apollodorus, only Aristophanes and Socrates have survived.

The Tripartite Soul

Plato’s tripartite soul is revealed to us in Bks IV, VIII, and IX of Republic, but its principles operate throughout the whole text. The ‘appetitive’ part of the soul is called the epithymetikon and it is primarily related to the objects that are our physiological needs and these require ‘wealth’ or power or an agency of some type to be appropriated. The ‘spirited’ part of the soul is called the thymoeides, and it is that part of the soul that is primarily concerned with the polemos or strife for victory and honour or just the struggle to be alive which is the primary reason for our focus on ourselves. The thymoeides is primarily concerned with ‘will’ and ‘will to power’. The logistikon is that part of the soul which desires the revealing of truth, and with the truth the genuine Good.

What a person’s soul or character is and how it will manifest itself depends on early experience and education and which desires come to govern our lives. The development or deterioration of the logistikon or ‘noetic’ part of the soul will occur when reason is only used as a calculative tool that determines which ‘appetites’ are stronger or more intense; but this reason in itself is unable to distinguish what is really good on its own. If the appetitive part of the soul predominates, the epithymetikon, it has to calculate according to how best to meet those appetitive aspirations (see Pausanias’ speech in Symposium). When the thymoeides comes to predominate, the technological way-of-being in the world comes forward. The thymoeides part of the soul will primarily be a product of and reflect the regime which rules in our being-with-others in our communities. In all of these cases mentioned, the soul will be unbalanced.

The “philosopher” is the person who achieves the maximum development of the desire for truth and the revealing of the Good and achieves the true essence of what a human being truly is. Human beings desire truth; not to do so is to become inhumane. Where the logistikon fails, the thymoeides part of the soul comes to predominate as a desire for power and as will to power. This will show itself in the desire for wealth and the possession of goods or that which can be “consumed”. The thymoeidic part of the soul acts as an intermediary with the other two parts and is pliable enough to let either of the other two parts come to predominate.

Knowledge of the Good is a condition for knowing what the Good is for the individual as well as the community, and it is a condition of social justice and individual justice which is the self-knowledge arrived at when the individual has the sophrosyne to see the relations of the parts of the soul to the whole i.e. knowledge of the parts to the whole. This knowledge brings about a balance to the soul and allows the individual to be just. Eros (as the cosmic whole of things) is the order (necessity, Time) in which a human being comes-to-be and through his good or evil actions is punished or rewarded accordingly.

Today, we refer to the three parts of the soul as the ‘personality’. Psyche is denigrated through the use of this word. The id, ego, and superego of Freud is a characterization of the lower eros of Plato only. The “blind love” of Freud replaces the love of the Good that is the Platonic Eros, and the Platonic Eros is driven by the “intelligence”, “mind” or “spirit” which he refers to “as fire catching fire”. For Freud, love is a case of contingency and chance. For Plato, Love is that infinitesimal element of the logistikon part of the soul which transcends necessity and chance. For Plato, the human being is like a chimera which has different forms of animals molded into one, such as a sphinx. The desires of the logistikon part of the soul are what reason considers as ‘the right thing to do’ for our actions and it is often at odds with the appetitive part of the soul.

The logistikon of the soul is two-faced: it is both calculative for the appetitive part which it receives from the thymoeidic part of the soul, and it has an impulse all its own which historically has been rendered as “reason”. Its calculative part reveals itself in our algebra which further becomes our way of controlling and commandeering the world we dwell in. The conflict in the soul is the manifestation of the aggressiveness and desire for victory that comes from the thymoeidic part of the soul and which can be used to fight against the appetites forming an alliance with reason or it can seek honours and victory against reason’s advice. This strife occurs in Section C of Plato’s Divided Line described in Bk VI of Republic. The choice involves our desire for immortality through love of one’s own that is the product of one’s own body or through “immortal fame”. The conflict manifests itself in that conflict that we have identified as “critical reason” and its conflict with the appetites.

The erotic “needs” to meet the physical, appetitive part of the soul i.e. drink and thirst, food and hunger and this “need” causes us to focus on ourselves only. These drives are for the objects themselves in order to “consume” them. These objects are “good” in themselves (and we call them “goods” in economics), but some are not good though they may appear to be good. The appetitive part of the soul relates to its ‘physical embodiment’, that which is subject to Necessity. The Necessary never desires the good in itself and in its blindness can choose the bad. The choice belongs only to the logistikon. The logistikon is ‘consciousness’. The “strife” occurs when the logos drives towards the good and the appetites seek objects independent of their goodness. The inability of the appetitive part of the soul to discriminate between what is good and bad is that it cannot establish a “limit” by itself but needs the logistikon with its desire for the good if it is to establish the appropriate limit.

The drive towards what the logos considers good and the appropriation of the goods that are the desires of the appetites is decisive for each human being because it determines what is to be done at a certain moment, which desires will lead our lives, and whether or not we become lovers of truth and whether we are able to get closer to the genuine Good. It is how we participate in justice.

The Soul and the Regime: Republic Bks IV, VIII and IX

Bk IV of Republic discusses the soul’s “physical embodiment”, its attachment to Nature and its significance as a mirror of the political order which surrounds it. In the Symposium, the speaker Phaedrus represents this level of the soul as it relates to eros. Phaedrus’ speech shows his membership in the oligarchic, timocratic social class to which he belongs. He is today’s “literary aesthete.”

Phaedrus’ name is significant in its meaning: it derives from the original Greek word phaino, which was one of the original names of Eros. The Greek word “phainesthai” (φαίνεσθαι) means “to seem”, “to appear”, or “to be brought to light”, thus it is associated with the Greek idea of “truth” (aletheia) but only with the truth’s idea of “seeming” to be true as “presence” (ousia) or appearance. It is the passive form of the verb “phainein” (φαίνω), which means “to show” or “to make appear”. Essentially, “phainesthai” describes something that appears to be or that is revealed but may not be really there.

These namings are significant in their relation to the epithymetikon part of the soul: the individual is led to the “appearance” or the “seeming” of that which, at first, appears to be good or beautiful. The “making” of the technites in the city will be of such a nature that they will use the images and representations given to them by that which is in order to bring into being things that are unnecessary needs for the soul and for the city. This is the underlying idea behind Socrates’ censorship of the poets from his ideal city, for the poets promote freedom as ‘license’ rather than freedom as thoughtful contemplation. Since Plato was a poet himself, we may presume that not all poets are included in this prohibition but only some types of poets. The Imagination as outlined by Plato in the Divided Line may be said to indicate the two-faced nature of the Logos: the imagination as a kind of thinking done by the lesser poets and technicians, and the Divine Imagination as used by the great poets (such as Plato himself) and the philosophers.

For Socrates, the analogy of the city and the individual (435a-b) proceeds from the three analogous parts in the soul with their natural functions (436b). The four virtues of the individual (by which “human excellence” is defined) are also shown in the polis by its organization. By using instances of the polemos or conflict in the soul, he distinguishes the function of the logistikon or thoughtful part from that of the epithymetikon or appetitive part of the soul (439a). Then he distinguishes the function of the thymoeidic or spirited part from the functions of the two other parts (439e-440e). The function of the logistikon part is the two-part thinking understood as rational calculation and as meditative, reflective, thankful consciousness. The spirited part, the thymoeides, is the two-fold experience of emotions driven by rage and anger or the care and concern that is love and the sense of otherness. That of the appetitive part or epithymetikon is the pursuit of material and bodily desires, the pursuit of beauty’s “surface”. Since this pursuit is the root cause for the creation of the city itself, it becomes a question of how this pursuit will be carried out as it is given in the city’s laws.

Socrates explains the virtues of the individual’s soul and how they correspond to the virtues of the city (441c-442d). A well-ruled city reflects the well-ruled souls of the individuals that comprise it. As a corollary, the poorly ruled city will be shown in the nature of the individuals who rule it and who are members of it. Socrates points out that one is just when each of the three parts of the soul performs its function (442d). Justice is the natural balance of the soul’s parts in performing their functions, and injustice is an imbalance of the parts of the soul in the subsequent actions that the individual carries out. (444e). With imbalance in the soul comes a subsequent loss of a sense of otherness. Socrates is now ready to answer the question of whether justice is more profitable than injustice that goes unpunished (444e-445a). To do so he will need to examine the various unjust political regimes and the corresponding unjust individuals in each (445c-e).

Socrates is about to embark on a discussion of the unjust political regimes and the corresponding unjust individuals but is prevented from doing so by Adiemantus and Polemarchus. He will return to this topic in Bk VIII. Instead, Socrates discusses the role of women as guardians and the need for the “ideal city” to sever ties to love of one’s own (which is an indication of the first of the impossibilities of the creation of the lower eros-free state and the possibility of its coming into being). The imposition of Polemarchus and Adiemantus is an indication of our need to compromise with the being of others in our worlds. One needs to also consider the relation between the ideas contained in the numbers 5 and 8 when reflecting on the content that is being discussed in both Bks V and VIII of Republic since the numbers as ideai will illuminate the content being discussed.

An example of the imbalanced soul is given through the story of the Ring of Gyges from Bk II of Republic. The story is related by Glaucon, the very “erotic” older brother of Plato, who is himself an “imbalanced soul” at the time of the dialogue. The purpose of the Republic is to instruct him. The premise of the story of Gyges is that we only act justly because we fear punishment should we not do so. Acting justly is not a good thing in itself. The ring gives one the “gift” of invisibility and anonymity. The ring provides one with the “ability” to dismiss one’s responsibility for one’s actions and thoughts, one’s words and deeds. It creates a gulf in the soul between one’s words and one’s deeds.

This “overlooking” of responsibility may be seen as analogous to what we understand as “intentional ignorance” which appears to be exacerbated by the “anonymity” that some believe the Internet provides today. “Intentional ignorance” can be seen as both a failure of the “imagination” (as outlined by Plato in the Divided Line) due to the lack of self-knowledge and an ironic desire for the “15 minutes of fame” that public recognition provides them. In the modern, 15 minutes is the best we can do, not believing eternal fame or glory are possible.

The belief in the anonymity which some think the Internet provides has given rise to those imbalanced souls being given a voice which allows them to obscure and obfuscate the truth regarding the real world about them, and this imbalance carries over to their being-in-the-world or worlds which they happen to construct and occupy. The avoidance of the recognition by many Christians (or those who wish to call themselves Christians such as J. D. Vance and the MAGA Christians in the USA) of the immorality of their immigration policies is an example of this “intentional ignorance”. This ignorance allows one to retain a belief in their own moral imperfections in spite of the Christian call to perfection (the cruelty, the racism, the inhumaneness of their dehumanization of their fellow human beings). Their evil is the outcome of self-deception and their lack of self-knowledge.

This intentional ignorance opens the door to lawlessness and licentiousness. Human beings who have become ensnared in this way of being-in-the-world behave irrationally and incoherently wherever the social, collective emotions rule. The social prestige that is given to a position of power becomes predominant in one’s desiring. One’s crimes and sins, one’s “stupidity”, are disconnected. “Stupidity” is a moral not an intellectual phenomenon. The metaxu, the eros, is destroyed. The metaxu as justice consists in establishing relations and connections between analogous things identical with those between similar terms, even when the things concern us personally (one’s own) and are an object of attachment for us. This is what the geometry of the “dialectical” purification of the logistikon is all about. It involves an act of will and an act of choosing.

In Bk VIII, the soul’s being with others in communities and its sense of justice is the focus of discussion. The first deviant regime from just kingship will be timocracy, the regime that emphasizes the pursuit of honor rather than wisdom and justice (547d ff.). The aristocratic individual, whose thymoeidic part of the soul is primarily concerned with honour and fame, becomes the oligarchic individual due to the soul’s desire for wealth over honour and fame. Wealth is more easily attained than honour and fame.

The oligarchic soul devolves into the democratic soul when the desires of the appetites come to predominate. The democratic soul then becomes the tyrannical soul. The order of the regimes presented is a descent of the soul of the individual and of the eros of that soul. The timocratic individual will have a strong spirited part in his soul and will pursue honor, power, and success (549a). This city will be militaristic. Socrates explains the process by which an individual becomes timocratic: he listens to his mother complain about his father’s lack of interest in honor and success (549d). The timocratic individual’s soul is at a middle point between the logistikon and the thymoeidic or spirited part of the soul.

Oligarchy arises out of timocracy and it emphasizes wealth rather than honor (550c-e). Socrates discusses how it arises out of timocracy and its characteristics (551c-552e): people will pursue wealth; it will essentially be two cities, a city of wealthy citizens and a city of poor people; the few wealthy will fear the many poor; people will do various jobs simultaneously; the city will allow for poor people without means; it will have a high crime rate. The oligarchic individual comes by seeing his father lose his possessions and feeling insecure he begins to greedily pursue wealth (553a-c). Thus he allows his appetitive part to become the more dominant part of his soul (553c). The oligarchic individual’s soul is at middle point between the spirited and the appetitive part.

Socrates’ discussion of democracy illustrates its relation to the epithymetic part of the soul. Democracy comes about when there is a gap between the rich and poor; the rich become too rich and the poor become too poor (555c-d). Too many unnecessary goods and desires make the oligarchs soft and the poor revolt against them (556c-e). In a democracy most of the political offices are distributed by lot (557a). The primary goal of the democratic regime is freedom understood as license (557b-c). People will come to hold offices without having the necessary knowledge (557e) and everyone is treated as an equal in ability (equals and unequals alike, 558c), and incompetent individuals will feel themselves entitled to offices for which they have no ability or fittedness. The democratic individual comes to pursue all sorts of bodily desires excessively (558d-559d) and allows his appetitive part to rule his soul for he is without limits. He comes about when his bad education allows him to transition from desiring money to desiring bodily and material goods (559d-e). The democratic individual has no shame and no self-discipline (560d).

Tyranny arises out of democracy when the desire for freedom to do what one wants becomes extreme (562b-c). The freedom or license aimed at in the democracy becomes so extreme that any limitations on anyone’s freedom seem unfair. Socrates points out that when freedom is taken to such an extreme it produces its opposite, slavery (563e-564a). The tyrant comes about by presenting himself as a champion of the people against the class of the few people who are wealthy (565d-566a). The tyrant is forced to commit a number of acts to gain and retain power: accuse people falsely, attack his kinsmen, bring people to trial under false pretenses, kill many people, exile many people, and purport to cancel the debts of the poor to gain their support (565e-566a). The tyrant eliminates the rich, brave, and wise people in the city since he perceives them as threats to his power (567c).

Socrates indicates that the tyrant faces the dilemma to either live with worthless people or with good people who may eventually depose him and chooses to live with worthless people (567d). The tyrant ends up using mercenaries as his guards since he cannot trust any of the citizens (567d-e). The tyrant also needs a very large army and will spend the city’s money to obtain it (568d-e), and he will not hesitate to kill members of his own family if they resist his ways (569b-c).

Bk IX discusses the differences between the tyrannical and the philosophic soul. Socrates begins by discussing necessary and unnecessary pleasures and desires (571b-c). Those with balanced souls ruled by the logistikon are able to keep their unnecessary desires from becoming lawless and extreme by imposing limits (571d-572b). The imposition of limits is done through the logistikon. Today, this tyrannical aspect of the soul is manifested in our desire for the “novel”, the “new” and in our creation of unnecessary desires.

In Bk VI of Republic Plato, in his discussion of the Divided Line, shows that the “know how” of the artists (poets) and technicians (scientists) devolves from the production or bringing forth of the products of their expertise to the bringing forth of ‘novelty’ or the ‘new’ with regard to those products in order to satisfy the desires of the appetites of those individuals who have bowed down to their tyrannical natures. The lust for the ‘new’ imposes itself on the eros of the poets and scientists so much so that it becomes a form of enslavement to production itself for its own sake. In the Republic, the search is for a form of thinking that will rise above this enslavement to the calculation of pleasures directed to the satisfaction of the desires and appetites that have been created. The tyrannical individual feels a sense of entitlement to the possessing of these objects of pleasure through wealth or other means.

The tyrannical individual comes out of the democratic individual when the latter’s unnecessary desires and pleasures become extreme; when he becomes full of the lower form of Eros or lust for power (572c-573b). The tyrannical person is mad with lust (573c) and this leads him to seek any means by which to satisfy his desires and to resist anyone who gets in his way (573d-574d). Some tyrannical individuals eventually become actual tyrants in the various worlds in which they happen to be (575b-d). Tyrants associate themselves with flatterers and are incapable of friendship because they are incapable of “dialectic” having lost contact with the logistikon parts of their souls. (575e-576a). The loss of a sense of otherness leads to an imbalance that results in a loss of any sense of justice.

Applying the analogy of the city and the soul in Bk IX, Socrates proceeds to argue that the tyrannical individual is the most unhappy individual (576c ff.). Like the tyrannical city, the tyrannical individual is enslaved (577c-d), least likely to do what he wants (577d-e), poor and unsatisfiable (579e-578a), fearful and full of wailing and lamenting (578a). The individual who becomes an actual tyrant of a city is the unhappiest of all (578b-580a). Socrates concludes this first argument with a ranking of the individuals in terms of happiness: the more just one is the happier (580b-c) for he possesses a sense of otherness.

Socrates distinguishes three types of human beings: one who pursues wisdom (the philosopher, driven by the logistikon part of the soul), another who pursues honor (the individual driven by the thymoeidic part of the soul), and another who pursues profit (those who are driven by the epithymetic part of the soul) (579d-581c). He argues that we should trust the wisdom lover’s judgment in his way of life as the most pleasant, since he is able to consider all three types of life clearly (581c-583a). Those who live the other types of lives are lacking in self-knowledge and do not know who they are. Because they do not know who they are and in their “intentional ignorance”, like Gyges, they have divorced themselves from any responsibility for the acts they do and they commit acts of evil ‘unknowingly’ for they are unable to distinguish the necessary from the good.

In his third argument regarding the happiness or unhappiness of the tyrant, Socrates begins with an analysis of pleasure: relief from pain may seem pleasant (583c) and bodily pleasures are merely a relief from pain but not true pleasure (584b-c). The only truly fulfilling pleasure is that which comes from an understanding that sees the objects which it pursues as permanent, that is, a way of being-in-the-world that moves beyond the images of that which is impermanent to the forms and ideas of that which is permanent (585b-c). Socrates adds that only if the logistikon part rules the soul will each part of the soul find its proper pleasure (586d-587a).

He ironically concludes the argument with a calculation of how many times the best life is more pleasant than the worst: seven-hundred and twenty nine (587a-587e) or 9 to the third power (9 x 9 x 9 or 999). This calculation outlines the difference between the Logos as number as we understand it in arithmetic, and the Logos as number understood as idea. Socrates discusses an imaginary multi-headed beast or chimera to illustrate the consequences of justice and injustice in the soul and to support justice (588c ff.). The physical characteristics of the soul and its desires produce a multi-headed hydra which the soul can vary and produce from out of itself. The bestial urges of the soul are the multiple appetites which constitute it. (See Blake’s illustrations of The Beast from the Sea.) The chimera which is the human soul in Bk IX is akin to, but not the same as, the Great Beast of Bk VI. The Great Beast of Bk VI (his number is 666) is the ‘social’ towards whom the political is directed while the beast of Bk IX is the individual soul of all human beings.

Education and the Training of the Soul

“Spiritedness” (anger, wrath, rage, emotions generally) is aligned with the logistikon in its polemos or strife against the appetites in its decisions on what is “the right thing to do” in order to defeat the urges of the appetites by imposing limits on them. The “spirited” part of the soul predominates when the lower part of the logistikon, that part which calculates, is ruling over the appetites. The calculations deal with the intensities of the pleasures which the appetites can give rise to. Today, what we understand as our technological way of being-in-the- world originates the activities that we pursue from the influence of the thymoeidic part of the soul. What we understand as evil originates in the thymoeides part of the soul, but human excellence also resides there.

Training the appetites is one of the aims of childhood education through the stimulation and weakening of the desires and wants in appropriate ways. The intention is to try to make sure that the individual can overcome the focus on the self in order to gain a sense of otherness and be able to participate in justice. The tyrant has released his lawless appetites not in dreams but in life: he is a “wolf”. The tyrant requires lawlessness in order to better achieve his ends. We are all potential tyrants. Unnecessary appetites can be gotten rid of in most cases. The creation of unnecessary appetites is the eros of the democratic regimes ruled by oligarchic capitalists who engage in these activities in order to increase their power through wealth. These unnecessary appetites show up as the desire for ‘novelty’ or the ‘new’ in the creation of ‘wants’ that are unnecessary for the human being.

The “timocratic man” becomes desirous of wealth and the possession of material things when he has found that the search and struggle for human excellence in itself is too difficult and he is too timid to achieve it in military campaigns. This love of possessions (the lowest form of “love of one’s own”) focuses on the “consumption” of the beauty of those things. The consumption of beauty is driven by the misguided belief that somehow one can find “immortality” through the possessions themselves. The corruption of an aristocratic regime and its descent to an oligarchic regime is due to the admission of the desire for wealth by its rulers: “He (the aristocratic man) secretly runs away from the laws like a child from his father” (549 a-b).

The love of wealth develops from the lack of a “musical education” in childhood, and the lack of a musical education then requires training by “force” and not “persuasion”. “Musical education” is contact with beauty and goodness, the mathemata (what can be learned and what can be taught) or what we understand as “reality”. Without training in “geometry” (“music”), the appetites grow without limits, especially the desire for wealth.

The logistikon part of the soul is trained through music (mathematics, geometry). The child is to receive ‘right stories’ in order to inculcate ‘right beliefs’. In democratic regimes, these stories are directed towards a sense of “entitlement” to the satisfaction of unnecessary appetites. “Democracy” has its evolution in this desire for wealth: the unnecessary appetites, created by the artisans and technicians, come to predominate. Power is the root of all evil and is most manifest in the desire for wealth. All worthy opinions and appetites are destroyed and the tyrant emerges. The philosopher and the tyrant are on opposite poles.

The thymoeides part of the soul, which has “anger” as a chief emotion and aggressiveness to confront the dangers of the world, is where andreia or will is to be found, and the will can be directed by will to power or the love of wisdom. For the Greeks, andreia is an episteme or way of knowing, so animals cannot have it. How is will connected to the logos?

At 588 d in Republic, the soul is depicted as a lion. The lion seeks and desires renown and predominance. “Spiritedness” is the desire for victory. It is “irrational”. It is the desire for competitive success and the esteem from others and oneself that comes with it. The tendency to form an ideal image of oneself in accordance with one’s conception of what is fair and noble requires social recognition to be confirmed. But this image is a false image of “self-knowledge”. This error is the reason so many individuals become involved in cults or movements that erase the hope of attaining a true sense of “self-knowledge” or “consciousness”. The “spirited” nature is incapable of discerning the good and the bad on its own and so attaches itself to the changeable, the physical. It makes the logos hold false opinions and judgements. The “uneducated” spirited nature becomes hard and ruthless instead of brave. At the same time, “artistic education” must be combined with sports so that the person does not become too soft and gentle. The greatest crimes are performed by natures of great eros in the thymoeidic part of the soul, but these natures are corrupted by deficient education which is usually the inability to impose limits on the epithymetikon part of the soul through the logos. The logos as rhetoric (the language of the masses) appeals to the thymoeidic and epithymetic parts of the soul.

The desire for wealth is the root of the appetitive part of the soul when it is “unlimited” by the logos. If knowledge does not confer honour, it is worthless. This gives importance to rhetoric as the logos of the timocratic, oligarchic and democratic man. Flattery and meanness of spirit result from subjecting the “spirited” soul to the “mob-like beast” (590b 3-9). With the desire for money and the constant satisfaction of the beast’s needs, the spirited element gets used to being trampled on so that it turns into a monkey instead of a lion. A sense of “victimization” results.

The two-fold nature of the thymoeidic part of the soul might be captured in the phrase “the call to arms”, for the call can be either the call from another human being whose beauty attracts one, or it can be the call to attain renown and glory in military deeds. Without proper training, the “spirited” part of the soul will behave in a beast-like way i.e. “irrational”. The logos is not merely reason as calculation. This is but one face or aspect of the two-faced Logos which relates to the two-faced Eros. The lack of moderation (sophrosyne) gives the terrible creature, the great beast with many heads, too much freedom (590 b). The individual is a microcosm of the polis of which he is a member and a further microcosm of the universe of which he is a part.

The epithymetikon part of the soul, because it is unlimited and seeks the satisfaction of unnecessary desires and appetites (what we would call “novelty” today) pulls the soul in their direction. Even in the best souls, the best one can do is to contain the appetites through the measuring of the logos and its imposing of limits. The appetites do not help the soul in its attempts to obtain the good.

If the “spirited” part of the soul is aptly trained by participation in “sports” and the logos trained “musically” to perceive the harmony of “right opinion” for what is good and what is not, what is honourable and what is not, what is worth fighting for and what is not, what is to be feared and what is not, “spiritedness” can then help the logistikon to achieve both individual and political goods founded on an understanding of reality (self-knowledge).

Courage is the knowledge of what is to be feared and what is not to be feared. The pull of the appetites towards bodily pleasures is what is to be feared most of all for it can become obsessive. It is destructive of right education which teaches right opinions and is destructive of the logos/logistikon as a whole. The highest courage is required for ‘gnostic’ knowledge of the Good which will give knowledge of political good as well as self-knowledge.

Animals have a kind of ‘rationality’, but it is not the rationality that reflects and calculates. The “aristocratic man” who lacks the right “musical education” and who is highly “spirited” does not have the “consciousness” to distinguish good from bad, true from false, and considers fighting and winning as ends in themselves. He has a distorted understanding of reality as a whole. The logos is in contact with the things that change and this leads to false judgements about what is honourable and what is not. The aristocratic man does not fight against real enemies i.e. the appetites and the enemies of the polis. The logos is poorly developed and the appetites are not trained to stay within ‘limits’. When this occurs, the person becomes wild and savage, a “beast”. The oligarchic, democratic and tyrannical men who have no “musical” training are incapable of restraining the appetites to stay within limits for they are overwhelmed by a need for will to power and do not remain within the limits of the necessary. The person becomes a ‘coward’. The timocratic man becomes psychologically unstable and becomes a lover of wealth. The overdevelopment of the appetites in the timocratic man are not governed by the logos. The environment provides the wrong conception of what is good.

The will that fights for victory and fame without the direction of the logos becomes pure savagery; and its corruption, weakened by the appetites, becomes a lover of wealth. With the proper training, the will becomes an ally of the logos in the search for truth and the Good. Courage is the manifestation of proper training supporting the right beliefs which are to be able to identify what is to be feared and dared. The most fundamental fight is that against the appetites.

The Logos/Logistikon

The logos is that through which we learn, reason and judge. It is most broadly what we understand as word and number. As word it encompasses rhetoric (the speech to many) and dialectic (the speech to a few). As number it encompasses number as calculation (arithmetic, algebra) and as geometry (mathemata that which can be learned and that which can be taught). Its dual aspects allows it to become an ally of the thymoeides in its making judgements regarding what is good or what is bad.

“Dialectical knowledge” (gnosis, Love) is the highest knowledge achievable. The logos is common to all human beings. It manifests itself in the desire for love and friendship. “Knowledge” exists in all of us, as do the appetites and the desire for recognition of our selfhood. What is understood as “reason” is a particular form of desire, a desire that compels the individual into finally achieving contemplation of the form of the Beautiful through to the idea of the Beautiful itself.

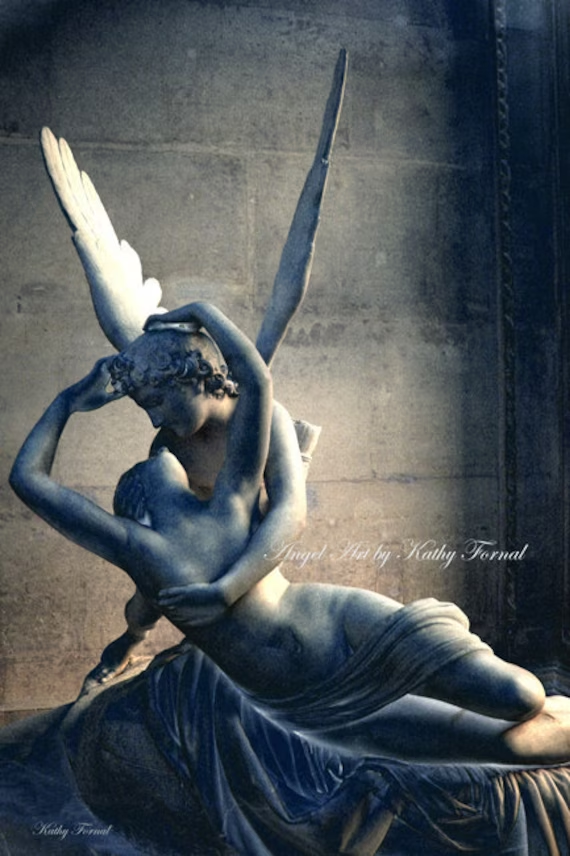

In its urging towards an ascent, Eros’ affect is to make us love the light and truth and hate darkness and falsehood. Care and concern for others and our sense of “otherness” develops from Eros’ erotic urge. This is what we understand as justice and is our participation in justice. Justice is experienced in both the thymoeidic and logistikon parts of the soul when these parts are in balance and are effectively carrying out their work. The ascent from the individual ego and its love of the part, experienced in the love of a single, beautiful other, to a knowledge of the whole and the love of the whole of things is a process that the immortal part of the soul (logistikon) undergoes in its journey towards “purification” from the love of the meeting of our own necessities and urges to the love of the Good. The tyrannic and democratic soul wishes to possess and consume all that comes before it. “Depth” arises from the ascent which is toward the centre of the sphere in the illustration provided. The descent brings about our desires for the surfaces of things, which is the lower form of eros. This descent is towards the outer circumference of the sphere. Evil is a “surface phenomenon” and eros is a part of it.