A few notes of warning and guidance before we begin:

The TOK essay provides you with an opportunity to become engaged in thinking and reflection. What are outlined below are strategies and suggestions, questions and possible responses only, for deconstructing the TOK titles as they have been given. They should be used alongside the discussions that you will carry out with your peers and teachers during the process of constructing your essay.

The notes here are intended to guide you towards a thoughtful, personal response to the prescribed titles posed. They are not to be considered as the answer and they should only be used to help provide you with another perspective to the ones given to you in the titles and from your own TOK class discussions. You need to remember that most of your examiners have been educated in the logical positivist schools of Anglo-America and this education pre-determines their predilection to view the world as they do and to understand the concepts as they do. The TOK course itself is a product of this logical positivism.

There is no substitute for your own personal thought and reflection, and these notes are not intended as a cut and paste substitute to the hard work that thinking requires. Some of the comments on one title may be useful to you in the approach you are taking in the title that you have personally chosen, so it may be useful to read all the comments and give them some reflection.

My experience has been that candidates whose examples match those to be found on TOK “help” sites (and this is another of those TOK help sites) struggle to demonstrate a mastery of the knowledge claims and knowledge questions contained in the examples. The best essays carry a trace of a struggle that is the journey on the path to thinking. Many examiners state that in the very best essays they read, they can visualize the individual who has thought through them sitting opposite to them. To reflect this struggle in your essay is your goal.

Remember to include sufficient TOK content in your essay. When you have completed your essay, ask yourself if it could have been written by someone who had not participated in the TOK course (such as Chat GPI, for instance). If the answer to that question is “yes”, then you do not have sufficient TOK content in your essay. Personal and shared knowledge, the knowledge framework, the ways of knowing and the areas of knowledge are terms that will be useful to you in your discussions.

Here is a link to a PowerPoint that contains recommendations and a flow chart outlining the steps to writing a TOK essay. Some of you may need to get your network administrator to make a few tweaks in order for you to access it. Comments, observations and discussions are most welcome. Contact me at butler.rick1952@gmail.com or directly through this website.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B-8nWwYRUyV6bDdXZ01POFFqVlU

A sine qua non: the opinions expressed here are entirely my own and do not represent any organization or collective of any kind. Now to business…

The Titles

1. Does our responsibility to acquire knowledge vary according to the area of knowledge? Discuss with reference to history and one other area of knowledge.

Title #1 has four key concepts involved in it: 1. responsibility; 2. to acquire, acquiring; to take possession of; 3. knowledge; 4. vary. You are asked to relate these four key concepts to history and one other area of knowledge.

When we say that we have a responsibility to acquire knowledge to ensure that we construct an accurate record of the past we ask ourselves “why?”. What is the end of an “accurate” account of the past whether it be our own or that of others? For what end is it our responsibility to know our History and learn from the past? Why do we not allow ourselves to remain ‘intentionally ignorant’ of the past if its learning is not convenient for us in the present?

“Responsibility” is inherently an ethical concept for it involves a being-with-others and a sense of otherness itself, something beyond ourselves. It implies a directive for ‘right’ action, an “I should do this” as the ‘ability’ to ‘respond’. The ability to respond was called dynamis by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. The ability to respond with moderation and wise judgement is what was known as ‘virtue’ to the ancients, what we understand as ‘human excellence’ today. The ability to respond involves the deeper question of justice since the sense of responsibility derives from the sense of a ‘debt owed’ to someone or something. To whom? to what? for what end?

At the moment, many of you are probably experiencing the “responsibility” to acquire knowledge from the “debt” you feel you owe to your parents for making your education possible. It is ‘right’ that you should do your best in your studies and take actions that will contribute toward that end. You have a ‘duty’ because you are ‘indebted’ to your parents. Or you may feel no sense of ‘indebtedness’ to anyone or anything. Or you may feel an indebtedness to yourself in that you do not want to be perceived as a moron and wish to achieve some social prestige through attempting to be the best that you can be in your studies. This desire is from our relations in our being-with-others. Stupidity is a moral phenomenon, not an intellectual one, and this is the essence of this question.

If stupidity is a moral phenomenon, then human beings have an obligation to acquire and take possession of knowledge. An obligation is a course of action that someone is required to take, whether that action be due to the legal or moral consequences or constraints inherent in the outcomes of the action or the not taking action. An obligation is an act of making oneself responsible for doing something. Human beings are under an obligation to think; we are not fully human if we do not do so. Obligations are constraints; they limit freedom. The obligation to think as the essence of human being is contrary to the notion that the essence of human being is freedom. Truth itself and its revealing is a constraint upon our freedom.

Those who are limited and intolerant in their thinking view knowledge of their History as limited by “subjectivity” and that it is only composed of the opinions that have become the “collective memory” of the society of which, by chance, they happen to be a member. Because of these subjective elements, they find that it is not essential to acquire knowledge of their past in order to build what they hope will be a “successful” future; self-knowledge is not essential to their happiness nor to their success. This is the ‘ignorance is bliss’ position where they believe their own empowerment will be the foundation of their future happiness; and their own goals and principles are decidedly short-term and entirely mutable depending upon the circumstances in which they find themselves. The lack of self-knowledge and the lack of a moral compass are one and the same thing.

As there are various types of human beings and various ways of thinking, there are also various areas of knowledge. In the IB, they have been identified as six areas of knowledge with further sub-divisions within each i.e. the Natural Sciences are sub-divided into Physics, Chemistry, and Biology. The ancients called these areas of knowledge the Seven Pillars of Wisdom for they made up a ‘knowledge of the whole’; wisdom is knowledge of the whole. The ancients arranged these pillars in a hierarchy; and while we do not speak of a hierarchy, it is easy to see that we hold knowledge in the sciences and mathematics and their applications as the most important areas of study in what we call the acquisition of knowledge today. Any analysis of IB enrollment statistics will demonstrate this.

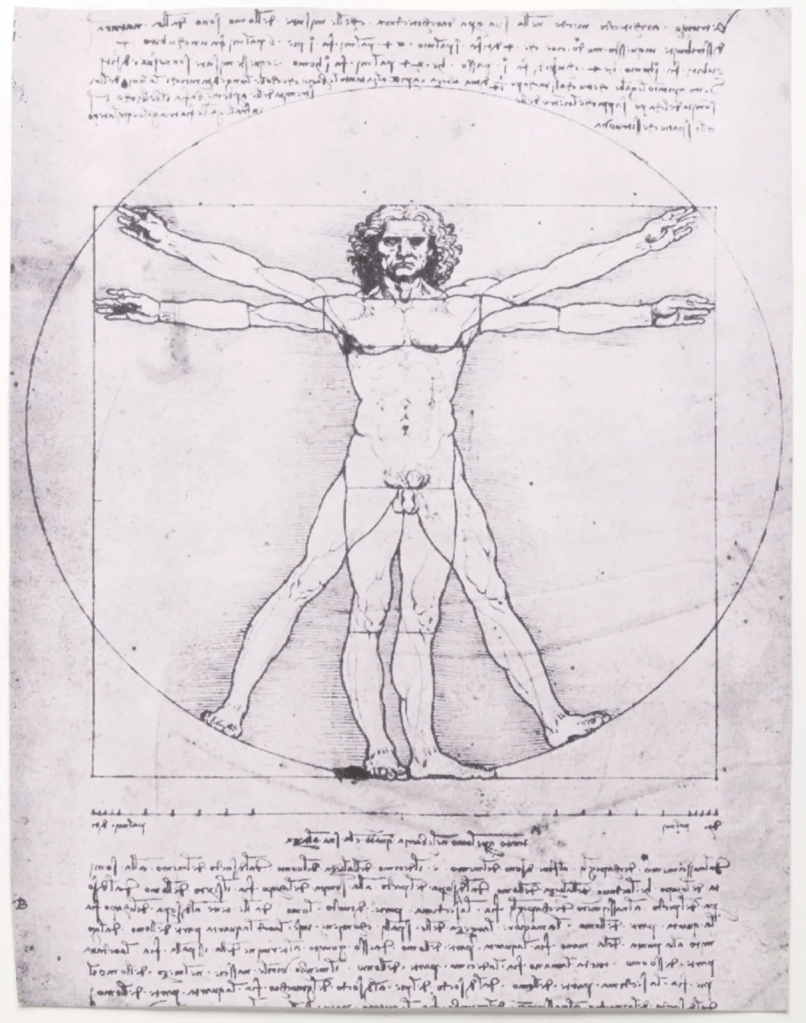

The sense of “responsibility” for acquiring knowledge in the sciences may be based on the belief that such knowledge will contribute to the continual development of human beings and continue to lead them toward “human excellence” or what the ancients once called ‘virtue’. It is an interesting irony in the history of the West that what was once considered the ‘masculinity’ of a man became the ‘chastity’ of a woman. This belief developed in that period of History known as the Renaissance. It is one of the foundations of what we call “humanism”, and from it flowered that way of being-in-the-world that we call “technology”. The relief of human beings’ estate through technology was a key to an understanding of justice. We felt, and still feel, an obligation and a responsibility to be just.

Our being-with-others is what is studied in the area of knowledge we call the Human Sciences. The Human Sciences, however, are unable to give us an account of what is the best manner or way of our being-with-others. This is due to the fact/value distinction that dominates their theoretical viewing of the world. They are incapable of answering this question, the ancient question of “what is the good life and how do you lead it?” since our sense of responsibility or duty is a ‘value’ that we have chosen or created and it has no ‘reality’ or validity in the world of ‘facts’. One manner of living or choice is equal to another; we call them ‘lifestyles’. The concept of ‘lifestyles’ is from the German philosopher Nietzsche. A pre-requisite for knowledge and success in the Human Sciences is moral obtuseness.

History is an account or narrative, the collective memory, of the significant actions that other human beings have taken and that have occurred over time in our being-with-others. It is more properly called ‘historiography’ (written history) as opposed to an understanding of ‘time as history’. The outcomes of those past actions have contributed to how we have come to understand and interpret, to have acquired and taken possession of, the meaning of those past actions and how they have impacted our understanding of ourselves. For example, who cannot be grateful for the stupidity of the Nazis which led them to understand Einstein’s and Heisenberg’s physics as ‘Jewish science’ and prevented them from funding research into the building of atomic weapons during WWII? Such stupidity was providential in that it prevented the Nazis from taking the ‘responsibility to acquire knowledge’ and it also prevented them from acquiring world domination.

Both History and the Human Sciences today are determined in their seeing by the ‘fact/value’ distinction where statements of fact regarding human actions are distinct from the ‘values’ that are the result of those actions. “Values” are what are subjective. In this perception, they are driven by what has been chosen to be the most highly ‘valued’ form of ‘knowledge’ which is to be found in the objective stance of the Natural Sciences. My statement above regarding the Nazis is a ‘value judgement’, a subjective statement. That I approve that it was good that the Nazis did not achieve world domination is a value judgement.

With the introduction of the word ‘good’ a whole host of other questions arise. For some, the fact that the Nazis didn’t achieve world domination was not a good end. A Europe in ruins was a better end than a Europe re-built from the ashes of those ruins. Similar thoughts are prevalent among many in today’s world. Social scientists in the USA prevent themselves from commenting upon the character of a man like Donald Trump since such comments would not be ‘professional’ but only ‘value judgements’. To have such a mentally disturbed man be their leader and their inability to warn against such outcomes reflects the madness that is deep within American society and the Social Sciences themselves.

The responsibility of acquiring knowledge is dependent upon what good end will result from our acquisition of that knowledge i.e. how will that knowledge contribute to our eudaemonia or happiness?. The type of end depends on the type of knowledge that is to be gained and applied. If I wish to make use of a banking app to do my banking then I have a ‘responsibility’ to learn how to make use of that app through becoming familiar with the knowledge of the procedures involved. The procedures and the theory are already embedded in the app i.e. the end is already embedded in the app. There is no choice involved other than the wish to make use of the app. There are many who will remain intentionally ignorant if the acquisition of whatever form knowledge may appear in does not contribute to their empowerment in some way for we equate empowerment with ‘happiness’.

In other writings on this blog, I have suggested that the lack of a moral compass so prevalent in today’s world, where there is no responsibility to acquire any knowledge other than that which allows one to seize and maintain power, is a primary result of the fact/value distinction, that beholding which is prevalent in the Human Sciences and History. Since domination and control is at the very heart of the stance of the physical sciences and these areas of knowledge wish to mirror those sciences, this should not be surprising. When good becomes a ‘value’ and ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’, then the outcome is not one of ‘universal tolerance’ but one of command and control, authoritarianism and fascism. Whether one is on the left or the right in their political thinking is irrelevant to this ultimate outcome.

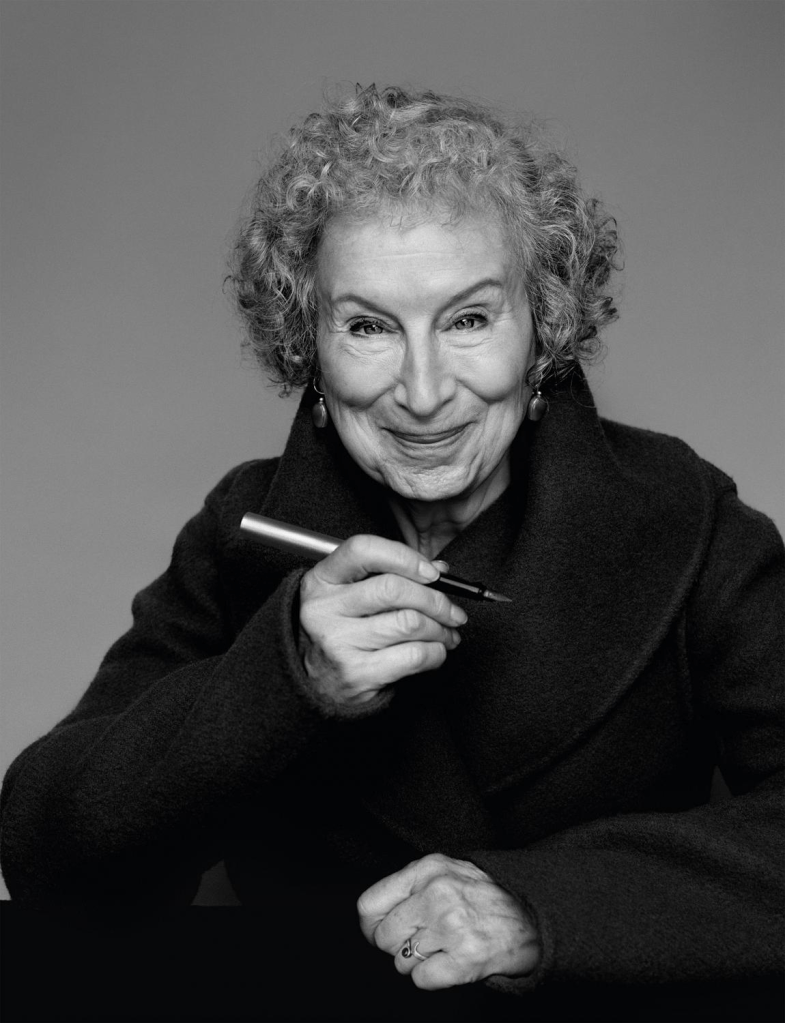

The Canadian writer Margaret Atwood once said that ‘all writing is political’. The desire to write down something is a desire that it be communicated to others at some point in time. Even a personal diary is a communication to a future ‘different person’ than the one producing the work of the diary in the present. It is an aid to memory. History is an aid to Memory, and contributes to our self-knowledge. The keeping of a diary may be said to be a first step on the journey to self-knowledge. This desire for self-knowledge is a recognition of the responsibility or ‘debt owed’ to oneself and others with regard to the compulsion we feel of the need to be fully human. This compulsion is our desire to seek ‘completeness’ and ‘perfection’ as a human being, which is not possible as we are the ‘perfect imperfection’ in our natures.

In other writings on this blog I have attempted to show that the key difficulty in receiving the beauty of the world today is that such a teaching and learning is rooted in the act of looking at the world as it is while the dominant sciences are rooted in the desire to change it. Our sense of ‘responsibility’ hinges on this dilemma. We cannot know or love an object or resource. In our research to learn the historical sources of the objects of the Arts around us, this study is merely for “aesthetic” purposes and enjoyment, not the fulfilment of a responsibility of having these works teach us about the beauty of the world or any notion of justice. We can learn about the past in such study; we cannot learn from the past. In other writings I have called this the two-faced nature of Eros.

2. In the production of knowledge, is ingenuity always needed but never enough? Discuss with reference to mathematics and one other area of knowledge.

The ‘production of knowledge’ are the ‘works’ that are the results of our ‘work’, the “produce” of our human making which mirrors the “produce” of Nature’s making. The production of knowledge is the products of our minds and hands. “Ingenuity” is a synonym for ‘novelty’, the ‘new’, the ‘creative’ which is an element brought to bear by the clever in our societies. To say that we are overwhelmed by the ‘novelty’ of technology today would be something of an understatement. We just begin to master all of the possibilities of our iPhones when another model is introduced.

But the corollary of all this novelty and ingenuity is an ever-increasing sense of mass meaninglessness, for we fail to find any real purpose for our novelty except that novelty as an end in itself.

The work that precedes the bringing forth of the ‘work’ is what is called ‘research’ in common parlance. This ‘research’ is conducted in multiversities and corporations throughout the globe. The “ingenuity” or “novelty” of the research is driven by the ‘vested interest’ that the individual, along with the institution, has in the outcomes of the research. In the past, research in History for example was a waiting upon the past so that we might find in it truths which might help us to think and live in the present. With the dominion of the fact/value distinction, such an end becomes lost; and with it, what we call our ‘moral compass’ becomes lost. Why?

All societies are dominated by a particular account of knowledge and this account lies in the relation between a particular aspiration of thought (the mind) and the effective conditions for its realization (the work of the hands): the work and its work. The work is knowledge, ‘the word made flesh’ so to speak. Our tools are an extension of our hands. We find the archetype and paradigm of thought and what we call thinking and, by extension, what we call knowledge in modern physics. Modern physics is the mathematical project. To pro-ject is ‘to throw forward’. The aspiration of our ‘throwing forward’ is ’empowerment’. In this throwing forward, some violence is done.

Our account is that we reach knowledge when we represent things to ourselves as objects, summonsing them before us so that they will give us their reasons for being as they are. To do so requires well defined procedures. This is what we call research. What we think knowledge is is this research for it is an essential effective condition for the realization or pro-duction of any knowledge. The work is the bringing forth or production of such knowledge bringing it to its completion. The bringing forth to completion was what was understood as ‘justice’ by the ancients. That which is brought forward is somehow ‘fitting’ for its purpose, its end. Justice is ‘fittedness’. In the technological society, the ingenuity behind the bringing forth has come to be an end in itself.

There are boundless examples of the varieties of ‘ingenuity’ that go into the research conducted in the sciences and the humanities. We live and breathe this novelty in our day-to-day lives. The calculus involved in mathematics results in the many apps brought forth to assist us in our use of our technological tools: the tools are the predicates of the technology and come to be through that technology; they are not technology itself in its essence.

The ‘knowing and making’ that is the word technology shows itself in the humanities in a dizzying number of theses with ingenious perspectives on the meaning of Beowulf (although any number of other examples could just as easily be found). The problem in the humanities is that when the work being examined is laid before us as object and our research is based on a review and critique of its historical sources, that work becomes dead for us. We can learn about the past; we cannot learn from the past: we can learn about the play King Lear, but we cannot learn from the play King Lear. The commandeering stance with regard to the past, which is necessary to research, kills the past as teacher and no amount of ingenuity will overcome this. If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, that which is beautiful is represented to a commandeering subject from a position of its own command and, thus, we cannot learn anything from the beautiful or that which makes it beautiful. The world as it is presented to us in the sciences has no place for the word ‘love’.

Most often, ‘ingenuity’ reveals itself in the paradigm shifts that occur in the histories of our areas of knowledge. A paradigm shift is not only a new way of thinking but a new way of viewing the world in which we live. The most dominant manner in which our world is viewed today is the ‘mathematical projection’. The ‘ingenuity’ within this world-projection is what we call by the cliche ‘thinking outside of the box.’ The history behind this viewing of the world is ‘ingenuity’ itself.

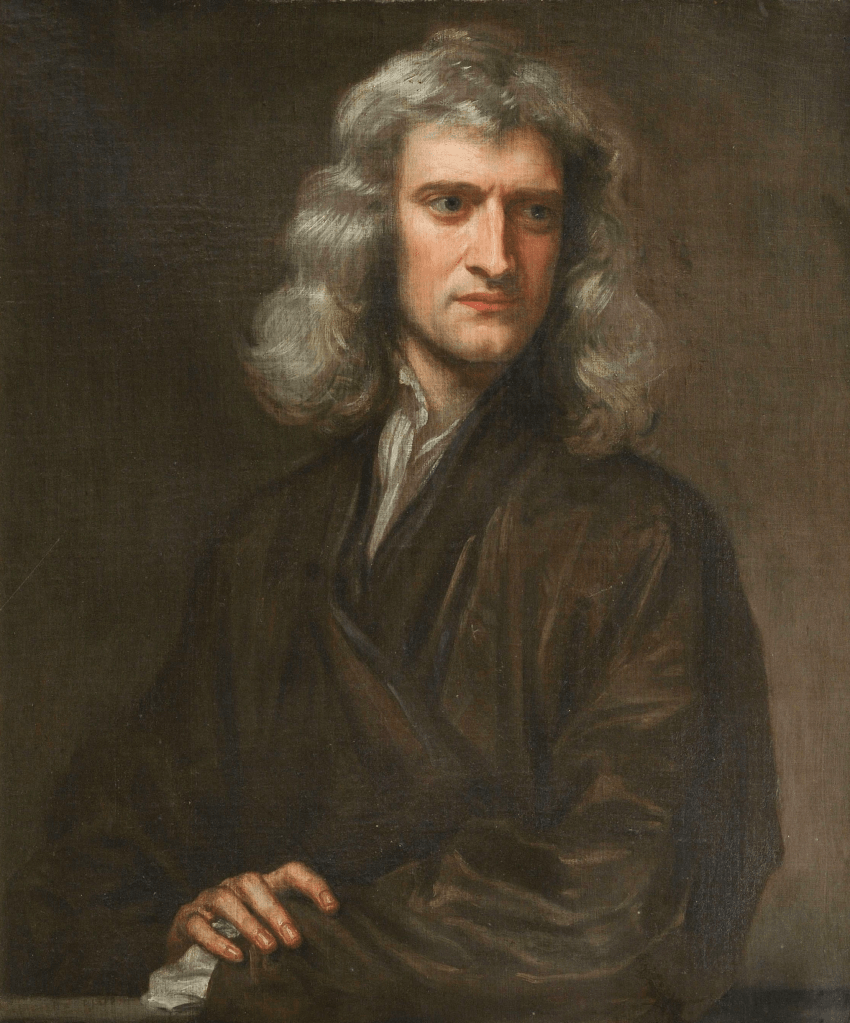

The mathematical projection and the ingenuity involved in it does not occur out of nowhere or out of nothing. Newton’s “First Law of Motion”, for instance, is a statement about the mathematical projection the visions of which first began to emerge long before his Principia Mathematica. Newton’s First Law states that “an object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force”. It may be seen as a statement about inertia, that objects will remain in their state of motion unless a force acts to change that motion.

But, of course, there is no such object or body and no experiment could help us to bring to view such a body. This is the ‘ingenuity’ in its view. The law speaks of a thing that does not exist and demands a fundamental representation of things that contradicts our ordinary common sense and our ordinary everyday experience. The mathematical projection of a thing is based on the determination of things that is not derived from our experience of things. This fundamental conception of things is not arbitrary nor self-evident. It required a “paradigm shift” in the manner of our approach to things along with a new manner of thinking. This is true ‘ingenuity’.

Galileo, for instance, provides the decisive insight that all bodies fall equally fast, and that differences in the time of the fall derive from the resistance of the air and not from the inner natures of the bodies themselves or because of their corresponding relation to their particular place (contrary to how the world was understood by Aristotle and the Medievals). The particular, specific qualities of the thing, so crucial to Aristotle, become a matter of indifference to Galileo.

Galileo’s insistence on the truth of his propositions saw him excommunicated from the Church and exiled from Pisa. Both Galileo and his opponents saw the same “fact”, the falling body, but they interpreted the same fact differently and made the same event visible to themselves in different ways. What the “falling body” was as a body, and what its motion was, were understood and interpreted differently. None denied the existence of the “falling body” as that which was under discussion, nor propounded some kind of “alternative fact” here. Galileo’s ingenuity consisted in his ability to view things in a very different way.

In Galileo, the mathematical becomes a “projection” of the determination of the thingness of things which skips over the things in their particularity. The project or projection first opens a domain, an area of knowledge, where the things i.e. facts, show themselves. What and how things or facts are to be understood and evaluated beforehand is what the Greeks termed axiomata i.e. the anticipating determinations and assertions in the project, what we would call the “self-evident”, the axioms. This self-evident, axiomatic viewing requires that things themselves lose any virtues that they may have in their particularity.

The mathematical projection provides the framework, the picture, that is the lens through which the world is viewed. Ingenuity is only acknowledged within this framework for knowledge production since outcomes must be reported in the language of mathematics. Ingenuity or novelty whether in an artistic process or the scientific method involves the discovering of innovative ways of devising experiments or utilizing clever analogies to explain complex concepts within these AOKs. Those who succeed in doing so are given Nobel Prizes as the result of their efforts.

3. How might it benefit an area of knowledge to sever ties with its past? Discuss with reference to two areas of knowledge.

Does Title #3 present a silly suggestion that it is possible for an area of knowledge “to sever its ties with its past” and that this severing may somehow be beneficial to it? is it possible for knowledge to occur in a vacuum? The fact that it is an “area of knowledge” implies that it has a past whose ‘picture’ has already been established for it. What we come to call ‘new knowledge’ is the change in perspective on the viewing of that which is permanently there. (See the Galileo example in Title #2.) Is this change of viewing what is meant by ‘severing’ here? Are we talking of paradigm shifts here? It should not be forgotten that everything will appear in a new light when that light is dimmed.

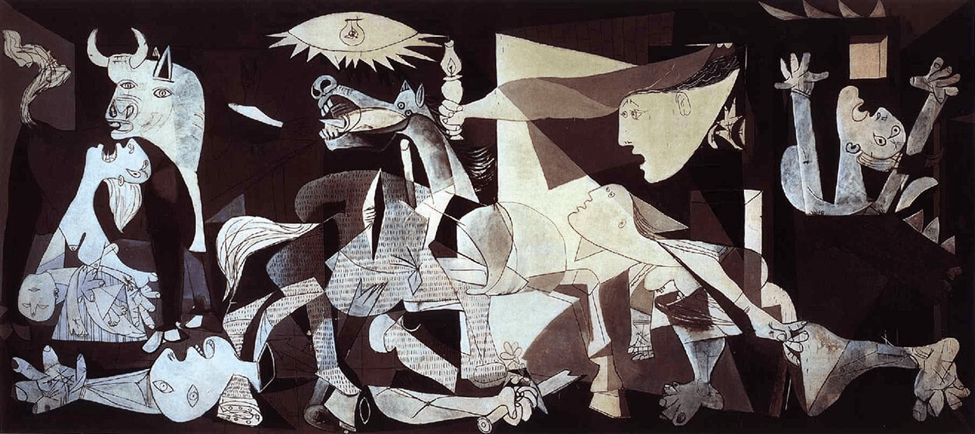

Much of what is said regarding Mathematics and the Natural Sciences in Title #2 would then be applicable here. Is Picasso’s cubism a severing of his ties with Art’s past? Does it not bring along with it the traditional viewing of three dimensional space and provide a new fourth dimension? Picasso’s theme of war in his Guernica has not changed. His viewing of a specific example of what war is presents a unique and horrible view of this ever-permanent subject. As human beings we live within a world which in itself does not change; our perspectives on it change, but the world itself does not. That we can now destroy other human beings with nuclear weapons does not change the permanent theme of our destruction of other beings. The lack of clarity in this question would cause me to avoid it or to question the lack of clarity itself.

The historian Thucydides believed that there was something essential in the nature of human beings, an essence, that was not subject to change. He also believed that the same was the case with regard to war and its causes. Modern historians do not believe there are such things as “essences” and so view the world in a very different way. Is such a different viewing a ‘severing’ of the ties with Thucydides? Or does it ultimately bring the modern historian finally into the position where Thucydides began his work? While we may desire to sever the ties with the past in our pro-duction of knowledge (is this due to our desire for novelty and ingenuity?) such a severing may not be possible if one is to continue pursuing the truth of things. Things will always appear different when they are viewed in a ‘new light’ even though that light may be dimmer.

Is modern atomic physics a ‘severing’ of its ties to the Newtonian physics of the past or the superstructure built upon the findings of those physics? Einstein is considered to be a completion of Newtonian physics while quantum physics is considered to be a more radical ‘severing’ of the viewing that had occurred in what is called classical physics. In the case of modern physics, this severing is due to its unique findings regarding the concepts of time and space and the object that is viewed with regard to the production of knowledge.

The rigor of mathematical physical science is exactitude. This has always been the case with science. Science cannot proceed randomly; it cannot sever its ties in its methodology, a methodology that has its roots in the past. All events, if they are at all to enter into representations as events of nature, must be defined beforehand as spatio-temporal magnitudes of motion. Motion is time. Such defining is accomplished through measuring, with the help of number and calculation. Mathematical research into nature is not exact because it calculates with precision; it must calculate in this way because of the adherence to its object-sphere (the objects which it investigates) has the character of exactitude and that exactitude is the mathematics itself.

In contrast the Group 3 subjects, the Human Sciences, must be inexact in order to remain rigorous. A living thing can be grasped as a mass in motion, but then it is no longer apprehended as living. The projecting and securing of the object of study in the human sciences is of another kind and is much more difficult to execute than is the achieving of rigor in the “exact sciences” of the Group 4 subjects. This is why statistics are used as the form of the disclosure of the conclusions that have been reached in the Human Sciences. In some investigations, the matrix mathematics of quantum physics is sometimes used to try to gain a precision into the analysis of the phenomenon under study with, usually, disastrous results. Such was the case in the economic recession of 2008. This is due to the fact that the domains of physics and of the human sciences are radically different.

The applications of the discoveries of modern physics have realized the new “ages” in which we live, the Atomic Age and the Information Age. As with all new “ages” in human history, something is gained but something is also lost. The highest point to which we look up to in our communities is no longer the church steeple or the statue of the Buddha; it is the ubiquitous communications towers sending the signals of our information to each other across the globe. When Galileo skipped over the viewing of the particular thing in its uniqueness in his effort to view the world mathematically, what was skipped over was a looking at the world as it is. This gave to human beings the difficulty, the deprival, of receiving the beauty of the world as it is. The removal of the love of and for the beauty of the world as it is was replaced by the desire to change it through domination and control.

As with all the things which human beings make, their viewing and their making is a double-edged sword: we are easily lulled into an appreciation of the benefits brought about by their realization at the cost of an inability to view how in fact we may be deprived by their realization. What deprivals are we witnessing in the discoveries of our new communications apparatus? What are the benefits resulting from mass meaninglessness and our understanding of knowledge as “information”? We can all see the benefits of artificial intelligence, but what deprivals are we experiencing with the arrival of this new technology?

4. To what extent do you agree that there is no significant difference between hypothesis and speculation? Discuss with reference to the human sciences and one other area of knowledge.

The English word hypothesis comes from the ancient Greek word ὑπόθεσις hypothesis whose literal or etymological sense is a “putting or placing under” and hence a providing of a foundation or basis for an assertion, claim or an action. Such a provision of foundations will be based on the historical knowledge that one has received and possesses with regard to the domain or area of knowledge that is under investigation.

“Speculation”, on the other hand, is the forming of a theory or conjecture without firm evidence. An hypothesis is ‘justified opinion’, while speculation is ‘unjustified opinion’. The word ‘speculation’ is usually associated with economics and is based on those judgements made by individuals which involve a substantial amount of risk since evidence is not available as to the ultimate outcome of the action that will be taken by an individual in their desire for gain in wealth and, subsequently, power. An hypothesis, on the other hand, depending on the domain or area of knowledge in which it is asserted, usually has historical findings to ground it. It is grounded in the principle of reason and looks for exactitude and certitude in its outcomes. The element of chance in speculation suggests that the opinion, claim or assertion is not fully grounded in the principle of reason. A current example would be investors placing their money in the DJT stock on Wall Street. There is an irrationality about it.

“Speculation” is sometimes based on ‘a gut feeling’. It is sometimes preceded by a “they said….” without any mention of who the ‘they’ are who have done the ‘saying’ and whether these ‘they’ are reliable or not in their speaking. There is a lack of surety, certainty in the grounds of the assertion because the assertion is not based on the principle of reason as no evidence or sufficient reasons are provided to justify the claim.

While both speculation and hypothesis are based on ‘theories’, an hypothesis is formed from a “theory” and a theory is a way of viewing the world from which develops an understanding of that world. The principle of reason provides the grounds or foundations for the ‘saying’. Theories or views (understandings) may produce true or false opinions. Our views of the world are based upon opinions, opinions that may or may not be justified. We cannot, for example, believe the assertion that Californian wildfires are caused by Jewish space lasers because sufficient reasons cannot be provided for the making of such an assertion. Such an assertion is mere speculation, and it is ‘risky’ due to its political implications in our being-with-others. An hypothesis requires evidence from experiment or experience that will provide sufficient reasons for the assertion contained in the hypothesis.

In both experience and experiment, a sufficient reason is sometimes described as the correspondence of every single thing that is needed for the occurrence of an effect (i.e. that the so-called necessary conditions are present for such an effect to occur). In the wildfires/Jewish space lasers example, there is no sufficient correspondence present between the effect and its possible cause. What is lacking is the ‘truth’ of the event: there are insufficient reasons for the correspondence theory of truth to apply. With speculation, nothing is ‘brought to light’ because no light is present.

We could, perhaps, also apply such a view to the indeterminacy principle of Heisenberg as long as randomness is incorporated in the preconditions that are mathematically included in the calculus. Such events occur at the sub-atomic level but they do not occur in our encounters with the objects that are present in our real experience of things. In our experience, the principles of Newton’s classical physics still apply. These conditions and their sufficient reasons do not apply at the sub-atomic level.

When we are asked ‘to what extent’, we are being asked for a calculation which can be expressed statistically or in language, a ‘this much…’. It implies a possibility of knowledge of the whole. Both hypothesis and speculation demonstrate similar content in some respects but they are ‘different’. If we claim that there is ‘no significant difference’, then we are saying that they are the Same. While some may presume a semantical equivalence between the two terms (which is the foundation of the question), it would appear that the submission of a hypothesis involves less risk in the truth or falsity of its claim than mere speculation which may be based on a ‘wishful thinking’ as to its outcome. Hypothesis relies on the surety of past knowledge and its discoveries while speculation rests in the hoped for gains that will result if such a speculation proves to be true.

5. In the production of knowledge, are we too quick to dismiss anomalies? Discuss with reference to two areas of knowledge.

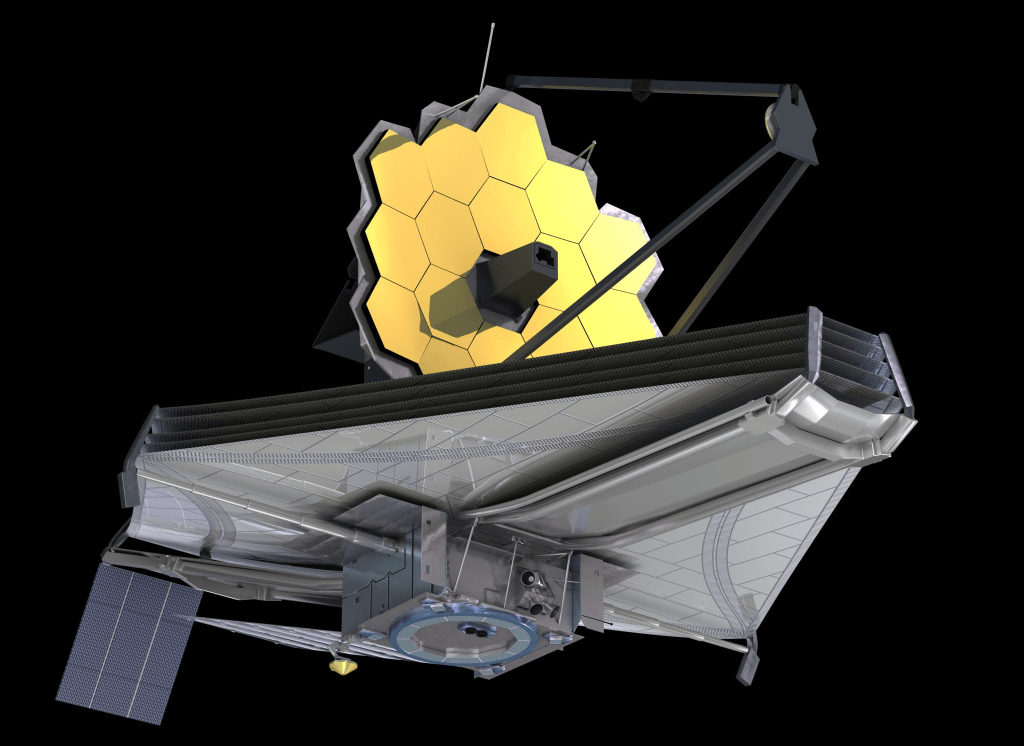

In recent years, the discoveries of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have produced a great number of anomalies for astrophysicists to attempt to resolve and which cannot be ignored especially with regard to the Big Bang Theory of the universe. The dates of the origin of the universe and the formation of galaxies are now being questioned. Often, rather than investigating anomalies further and considering an overhaul of existing knowledge, anomalies are dismissed as ‘exceptions’ to the rule rather than a justification to question the rule itself. Such discussions are now occurring among the scientists in the world of astrophysics. Such anomalies and discussions will provide theoretical work for scientists for years to come and may require or provide a paradigm shift in the area of knowledge called astrophysics.

Anomalies are often the prompt for a paradigm shift in the sciences causing us to challenge existing beliefs and ideas. In Physics, perhaps the greatest anomaly lies in the Heisenberg indeterminacy principle. In the experiments conducted in the early 20th century, results often occurred which could not be corresponded to the physics of Einstein. With Heisenberg’s indeterminacy principle, the mathematical account for those outliers could be accounted for and shown mathematically.

In everyday life, calculating the speed and position of a moving object is relatively straightforward. We can measure a car traveling at 60 miles per hour or a tortoise crawling at 0.5 miles per hour and simultaneously pinpoint where the car and the tortoise are located. But in the quantum world of particles, making these calculations is not possible due to a fundamental mathematical relationship called the uncertainty principle.

Formulated by the German physicist and Nobel laureate Werner Heisenberg in 1927, the uncertainty principle states that we cannot know both the position and speed of a particle, such as a photon or electron, with perfect accuracy; the more we nail down the particle’s position, the less we know about its speed and vice versa. Because sub-atomic particles behave like waves in quantum viewing, the measurements we make appear to be uncertain or inaccurate, but this is the case with wave-like properties. In the world of our experience, a chair behaves like a chair. There is a gap present between the behaviour and the nature of sub-atomic particles and the objects of our common everyday experience.

In the Human Sciences, Donald Trump is seen by many as an ‘anomaly’ outside of the normal political activity of the community that is the USA. Is this really the case? Is he really an ‘anomaly’? If so, how is it possible that he is the Republican nomination for President? That Donald Trump is the fertilizer that brought about the flowering of the growth that was the corruption already present within the institutions of the American system of government is more of an indication of the failure of the seeing, the consciousness and conscience, present in the ‘wishful thinking’ of those who observe American politics whether they be media, academics or political pundits. Is it possible for a true outlier to achieve political power or must there be common elements present in both the aspirer for power and in those who will hand that power over to him? Was Adolf Hitler an ‘outlier’ in the German politics of the 1920s and 1930s?

Because of the manner of our viewing of the world, we usually cannot see what we are not looking for, so anomalies are often missed and when they are sighted they are usually met with the response “That’s odd”. If they are seen, they are usually ignored because people and their institutions and organizations are predisposed to confirmation bias, focusing on what aligns with their mental models rather than what violates them. In the Human Sciences, for instance, the word “anomaly” is most often used to dismiss a data point as unrepresentative and irrelevant. Even if we do not ignore anomalies, we may not try to interpret or explore them. Does an anomaly such as Donald Trump get over 70 million votes in a democracy? Why, for example, did it take so long for the symptoms of PTSD (Post-traumatic Stress Disorder) to be recognized and to be systematically dealt with?

6. In the pursuit of knowledge, what is gained by the artist adopting the lens of the scientist and the scientist adopting the lens of the artist? Discuss with reference to the arts and the natural sciences.

The Arts and the Sciences have complementary histories of evolution. This history may be understood as the manner in which both of these human activities have pursued knowledge with regard to their understandings and relationships to what is understood and interpreted as Nature or Otherness. Just as Art pursues “object-less” representations of abstractions conceived in the mind so, too, does science attempt to understand our being-in-the-world through the projection of mathematical abstractions on what we think ‘reality’ is. Both art and science see themselves as ‘theories of the real’. While art must withstand the question Is it art? science, too, must withstand the question Is it science? particularly with regard to the Human Sciences. The responses to these questions can be either profound or downright silly.

Science is what we understand by ‘knowledge’, ‘knowing’. Art is what we understand by ‘making’, the performance that results in a ‘work’, whether that work be a painting, a musical composition, or a pair of shoes. Knowing and making are what we mean when we speak of “technology”, the combination of the two Greek words techne or ‘making’ and logos or ‘knowing’. The combining of these two words is something that the Greeks never did and would never do. The word was first coined in the 17th century with the rise of humanism. The ‘adopting of the lens’ of the artist by the scientist, or of the scientist by the artist is, obviously, a constant in the modern world since the outcomes or products of technology are the objects that we see all about us and which we use on a daily basis. The scientist’s knowing and the artist’s making are on display before us at this very moment if we are using a computer, an iPad or a handphone to read this blog.

The pursuit of science is the human response to a certain mode or way in which truth discloses or reveals itself. Science arises as a response to a claim laid upon human beings in the way that the things of nature appear. The sciences set up certain domains or areas (physics, chemistry, biology) and then pursue the revealing that is consistent within those domains. The claim laid upon human beings is to reveal truth, for it is in the revealing of truth that we are truly human. We are not fully human if we do not do so.

The domain, for example, of chemistry is an abstraction. It is the domain of chemical formulae. Nature is seen as a realm of formulae. Scientists pose this realm by way of a reduction; it is an artificial realm that arises from a very artificial attitude towards things. Water has to be posed as H2O. Once it is so posed, once things are reduced to chemical formulae, then the domain of chemistry can be exploited for practical ends. We can make fire out of water once water is seen as a compound of hydrogen and oxygen. In the illustration of Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers”, we have the chemical formula for the physical composition of Van Gogh’s yellow paint. While interesting, it tells us absolutely nothing of the painting itself and of the world or the artist that produced that painting. This is the situation with many recent discoveries in science, particularly the Human Sciences: their discoveries are interesting but tell us absolutely nothing meaningful about the world we live in.

The things investigated by chemistry are not “objects” in the sense that they have an autonomous standing on their own i.e. they are not “the thrown against”, the jacio, as is understood traditionally. For science, the chemist in our example, nature is composed of formulae, and a formula is not a self-standing object. It is an abstraction, a product of the mind. A formula is posed; it is an abstraction. A formula is posed; it is an ob-ject, that is, it does not view nature as composed of objects that are autonomous, self-standing things, but nature as formulae. The viewing of nature as formulae turns things into posed ob-jects and in this posing turns the things of nature, ultimately, into dis-posables. The viewing of water as H2O, for example, demonstrates a Rubicon that has been crossed. There is no turning back once this truth has been revealed. That water can be turned into fire has caused restrictions in our bringing liquids onto airplanes, for instance, for they have the capability of destroying those aircraft.

“What we observe is not nature in itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning. Our scientific work in physics consists in asking questions about nature in the language that we possess and trying to get an answer from experiment by the means that are at our disposal.”–Werner Heisenberg

What is the physicist Heisenberg saying here? The language that the scientist possesses is the mathematical projection or abstraction that is placed over the object that is questioned, but the object that is questioned can only appear in a manner pre-ordained by the nature of the questioning itself. Through experiment, the response to the question posed must be in the form of the mathematical language used: nature must respond ‘mathematically’. But what that nature is is not what has been traditionally understood as ‘nature’. The response must be consistent. The logos that is mathematics is this consistency.

For Heisenberg, what has been called nature has been ordered to report mathematically and this is the first level of abstraction. The mathematical viewing of nature makes the ob-ject of science non-intuitive. What does this mean? In the example above of Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers”, the color yellow is reduced to a formula describing a variety of chemical reactions between various compounds. In physics, the color yellow would be reduced to a formula describing a certain electro-magnetic wave. A person can then possess a perfect scientific understanding of the color yellow and yet be completely color blind i.e. they could not experience Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” in its ‘reality’. In the same fashion, a person who knows yellow intuitively by perceiving yellow things such as sunflowers will fail to recognize the scientific formula as representing her lived experiences of the color yellow. This is what is meant to say that science is non-intuitive and is, thus, an abstraction.

Like the abstractions of the mathematical projections in physics and the projection of formulae in chemistry, abstract art is an art form that does not represent an accurate depiction of visual reality, communicating instead through lines, shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks. Abstract artists may be said to use the lens of the scientist with their varieties of techniques to create their work, mixing traditional means with more experimental ideas. Their work is a product of the mind (or the unconscious) and does not correspond to the Otherness that is what we understand as our being-in-the-world. Jackson Pollock described abstract art as “energy and motion made visible.” Pollock’s art, in a way, attempts to approach the art that is available for us through the cinema.

The examples provided are what we might call the “pure” theoretical scientists or the “pure” abstract artists. What is ‘gained’ by such ‘abstract’ attempts? What is gained is that through the discoveries of the scientists and the artists many applications of their findings are brought into our real world in a great variety of forms and products. The computer before us is a product of the application of the discoveries of quantum mechanics. It is a seamless connection between knowing and making, art and science, the lens of the scientist and the lens of the artist.

It is easy to see what has been ‘gained’ in the coming together of the arts and sciences that we know as technology. It is much harder to see what has been lost in this development. As I have shown in other writings on this blog, an indispensable condition of a scientific analysis of the facts is moral obtuseness. The lens of both the modern day scientist and the modern day artist are not moral lens. Modern art, in its following or mirroring of the seeing of the sciences, contributes to this moral obtuseness among human beings. Since art is essential in our being-with-others in a ‘real’ world, this does not bode well for the future.

“The following 12 concepts have particular prominence within, and thread throughout, the TOK course:

“The following 12 concepts have particular prominence within, and thread throughout, the TOK course: