Note to Readers:

Many teachers of Theory of Knowledge begin their programs or courses with Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Plato’s Allegory is from Bk VII of Republic. To understand Plato’s Allegory, I believe it is necessary to gain an understanding of the Divided Line that Socrates discusses in Bk VI of the dialogue. The Divided Line is the logos (the “word”) that is prior to the praxis (the “deed”) of the Allegory. Understanding the Divided Line will help to answer many of the questions that may arise from any discussion of the Allegory.

In the writings of Plato, the link between learning and “studious effort” is emphasized, and education is a necessity for the citizens of a political community who are in a constant strife against the evil of tyranny, a danger co-eval with living in communities. Learning is a “quest”, a journey, the goal of which is the acquisition of knowledge at some future point in time. This quest is both an individual and communal endeavour. The “quest” is prompted by a “question”, and by the perplexity that is a result of not knowing.

The greatest obstacle to knowledge and to the quest is “ignorance”. The greatest ignorance is thinking that one knows something while not knowing it. Knowledge of knowledge and ignorance is inseparable from knowledge of what is good and what is evil. That which is not known to us is present, though hidden, “within” us and can be brought out by “remembrance” and “re-collection”. Knowledge is a “whole”. Only knowledge as “wholeness” can securely guide our actions so as to make them beneficial and good. Knowledge is arete: “human excellence” or virtue. Knowledge of our ignorance is linked to a knowledge of an all-embracing good on which everything we call good depends. Socrates is aware of the immense distance which separates him from the goal which he wishes to attain: he knows the immense distance which separates the necessary from the Good. He claims expertise only in the knowledge of eros, the ‘neediness’ of human beings, who are the perfect imperfection.

The outline of the quest for knowledge has been given to us in various forms in our myths and narratives. Socrates opens Bk. VII of Republic with the following introduction: “Next then, I said, here is an image to give us an aspect of the essence of our education as well as the lack thereof, which fundamentally concerns our Being as human beings.” We see in this introduction to the parable or allegory of the Cave the necessary connection between education, our being as human beings, and our being-in-the-world. In the telling of this tale, there is no separation of “facts” and “values”, no separation of our being as human beings and our being in communities. They are both, ultimately, inseparable. Ontology, epistemology, and ethics are inseparable.

On any given weekend, we can go to our cinemas and hope to see some example of what the Greeks called arete, “human excellence”, “competence”, or “virtue” in the many heroes on display there. These images or myths are mirrors which throw a reflected light on the conditions and predicaments of our being-in-the-world, our human lives. The monsters in myths are various projections of the human soul (the Minotaur in the labyrinth, for example, as an image of the individual human soul, or the Great Beast of Bk VI of Republic being the image of the ‘collective soul’), and in the unfolding action we hope to see some suggestions and solutions to the predicaments of our lives which are embodied in the agon with these monsters. The action of learning conveys the truth about learning. It is not a “theory of knowledge” or “epistemology” but the very effort to learn, to engage in the quest. It is a way of being-in-the-world. We have called it the desired goal of becoming a ‘life-long learner’; we believe that this is what “human excellence” is. The Divided Line of Plato in Bk. VI of Republic and the allegory of the Cave in Bk. VII are parallel and represent images or eikones of the quest towards knowledge, primarily knowledge of the Good. Both images involve action of some kind and these actions involve the unconcealment of truth at various levels.

In the dialogue Phaedrus, Socrates tells a story regarding the invention of writing. The story is said to be of Egyptian origin and regards the invention of writing by Theuth and the criticism of that invention by Thamus. Thamus’ criticism rests in that he believes writing brings about “forgetfulness” and substitutes external marks for ‘genuine re-collection’ from within the human soul. This lack of re-collection (anamnesis through dianoia) erodes that conversation among friends (dialectic) that leads to truth. Socrates mocks Phaedrus by saying that “today’s young in their sophistication…look less to what is true than to the personality and origin of the speaker”. One could further mock the youth of today and say that with today’s social media, artificial intelligence, and the internet, not even the origin and personality of the “speaker” is questioned as there is a preponderance of anonymity prevalent and a preponderance of referring to the “they” in the “they said…”. This lack of concern for truth on the social or communal level impacts the individual concern for arete or what may be conceived as human excellence on the individual living in the community.

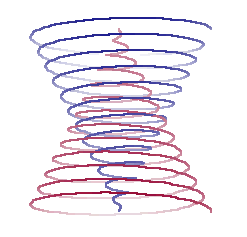

There is an analogy here between Thamus’ criticism of writing in the story of Theuth and the arrival of artificial intelligence today: the destruction of genuine “re-collection” and thought within leads to a lack of self-knowledge which, in turn, destroys the potential for the thoughtful conversation and engagement between “friends”, the dialectic necessary for the attainment of the Good. The “imitated” thought is not a thought, and artificial intelligence is nothing more than “imitated thought”. The beginning sense of wonder is corroded because one thinks one knows what one does not. (The Fool of the Tarot and the ascent of the divided line is parallel to the journey out of the Cave to a vision of the Good and the descent back into the Cave. This image of ascent and descent is represented by the two cones and triangles embodying the square illustrated below. One should reflect on the connection between these figures and Da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” provided later in this writing.)

Plato’s discussion of the Divided Line occurs in Bk VI of his Republic. In Bk VI, the emphasis is on the relation between the just and the unjust life and the way of being that is philosophy. It is emphatically ethical for the just life deals with deeds, not with words. The philosophic way of being is erotic by nature. To be erotic is to be “in need”; sexuality is but one manifestation of the erotic, though a very powerful manifestation of this human need. Socrates must chide his interlocutor Glaucon on a number of occasions in this part of the dialogue, for Glaucon is ‘erotic’ and is driven by militaristic and sexual passions and, because of such drives, he has a predilection for politics, for seeking power within the community or polis, from which our word ‘politics’ derives.

Bk VI of Republic emphasizes the relation between the just and the unjust life and the life that is philosophy. The just life is shown by “the love of the learning that discloses (unconceals) the being of what always is and not that of generation and decay.” Those who love truth and hate falsehood are erotic by nature i.e., they are ‘needing’ beings by nature; they feel that something is missing; they feel that they are not ‘whole’. Care and concern develop from this; the love of the whole (the Good) is a great struggle or polemos in its attainment. To love the “part” is to be “channeled off” in another direction. This two-fold or “double” learning is captured in the two types of thinking that are referred to as dianoia and diaresis. This two-fold or “double” possibility of learning is emphasized in the construction of the Divided Line and is illustrated by the different directions of the gyres shown previously.

The philosophic soul in reaching out for knowledge of the whole reaches for knowledge of everything divine and human. It is in need of knowledge of these things, to experience and to be acquainted with these things. The non-philosophic human beings are those who are erotic for the part and not the whole. They are deprived of knowledge of what each thing is because they see by the light of the moon and not the sun (the dialogue of the Republic takes place over night and ends with the rising of the sun in the morning); their light is a reflected and dim light. They have no clear ‘pattern’ in their souls and they lack the experience (phronesis or “wise judgement”) that is tempered with sophrosyne or moderation that they have acquired through suffering or through the experience of need. The philosophic soul has “an understanding endowed with “magnificence” (or “that which is fitting for a great man”) and they are able to “contemplate all time and all being” (486 a). They are “prophets”. The philosophic soul has from youth been both “just and tame” and not “savage and incapable of friendship”. (See the connection to The Chariot card of the Tarot where the two sphinxes, one white and one black representing the mystery of the soul, are in contention or strife (polemos) with each other. The sign over Plato’s academy properly reads that “No one enters unless they are capable of friendship”).

In looking for the philosophic way of being in the world, Socrates concludes: “…let us seek for an understanding endowed by nature with measure and charm, one whose nature grows by itself in such a way as to make it easily led to the idea of each thing that is.” (486 d) The philosophic soul is such by nature i.e., it grows by itself. Is this all souls or only some souls? Are all souls capable of attaining the philosophic way of being? The modern answer to this question has been a “yes”, while the ancient answer appears to be a “no”.

The philosophic soul is “a friend and kinsman of truth, justice, courage, and moderation.”(487 a) The philosophic soul is able to grasp what is always the same in all respects. (B and C in the Divided Line) The distinction between the philosophic soul and its “seeing” is shown by its contrast to the “blind men” who are characterized as: 1. Those who are erotic for the part and not the whole; 2. Deprived of knowledge of what each thing is; 3. See by the light of the moon or by the opinions established by the technites’ fire, the fire of the artists and technicians; 4. Have no clear pattern in the soul; and 5. Lack experience phronesis or “wise judgment” tempered with sophrosyne or moderation.

Socrates uses an eikon (AB of the Divided Line) to indicate the political situation prevalent in most cities or communities. The eikon uses the metaphor of “the ship of state” and the “helmsman” who will steer and direct that ship of state. The rioting sailors on the ship praise and call “skilled” the sailor, the “pilot”, the “knower of the ship’s business”, the man who is clever at figuring out how they will get the power to rule either by persuading or by forcing the shipowner to let them rule. Anyone who is not of this sort and does not have these desires they blame as “useless”. They are driven by their “appetites”, their hunger for the particular (i.e., what Plato described as human beings when living in a democracy. This is the reason Plato places democracy just above tyranny in his ranking of regimes from best to worst, tyranny being the worst, since both of these regimes are ruled by the appetites and not by phronesis and sophrosyne. Democracy’s predilection for capitalism is a predicate of the rule by appetites).

The erotic nature of the philosophic soul “does not lose the keenness of its passionate love nor cease from it before it has grasped the nature itself of each thing which is with the part of the soul fit to grasp a thing of that sort, and it is the part akin to it (the soul) that is fit. And once near it and coupled with what really is, having begotten intelligence and truth, it knows and lives truly, is nourished and so ceases from its labour pains, but not before.” (490 b) The terminology used here is that of love, procreation and childbirth. The grasping of the ‘real’ is not the taking possession of abstract concepts. With regard to the Divided Line, this is the analogy of B=C: the world of the sensible, the visible “is equal to” the world of the Thought or Thinking: the mathemata or “that which can be learned and that which can be taught.” There is a world which is beyond that which can be learned and that which can be taught. Socrates sees himself as a mid-wife, helping to aid this birthing process that is learning. (Notice that this indicates the descending motion within the cones that were shown in the earlier illustration after a gnostic encounter with the Idea of the Good.)

By examining Plato’s dialogue Meno, we can see the “double” nature of learning as understood in the Greek term anamnesis or “re-collection”. Meno, a Greek from Thessaly history tells us, was an unscrupulous man eager to accumulate wealth and subordinated everything else to that end. He is known to have consciously put aside all accepted norms and rules of conduct; he was perfidious and treacherous, and perfectly confident in his own cunning and ability to manage things to his own profit. He was also notable for being extremely handsome. In coming upon Socrates in one of his visits to Athens, he asks Socrates what Socrates thinks “human excellence” or arete is. Arete is usually translated as “virtue”. Notice the irony present here.

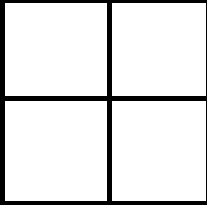

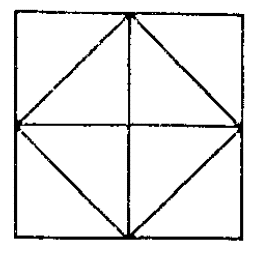

In the Meno dialogue of Plato, Socrates attempts to show how learning is “re-collection” by using one of Meno’s slave boys as an illustration of how learning can come about. In the example given, Socrates’ question to the young slave boy is: “Given the length of the side of a square, how long is the side of a square the area of which is double the area of the given square?” (85d 13 – e 6) As we know (and Meno does not), the given side and the side sought are “incommensurable magnitudes” and the answer in terms of the length of the given side is “impossible” (if post-Cartesian notions and notations are barred). The side can only be drawn and seen as “shown”:

Stage One: (82b9 – a3) The “visible” lines are drawn by Socrates in the dust emphasizing their temporality, their being images, eikones. There are two feet to the side of the “square space”. The square contains 4 square feet. What is the side of the “double square”? The slave boy’s answer: “Double that length.” The boy’s answer is misled by the aspect of “doubleness”. He sees “doubleness” (as we do) as an “expansion” of the initial square rather than a “withdrawal” of that square to allow the “double” to be. We need to keep this “double” aspect in mind when we are considering the seeing and meaning of the Divided Line later on.

Stage Two: When the figure is drawn using the boy’s response (“double that length”), the size of the space is 4 times the size when only the double was wanted. The side wanted will be longer than that of the side in the first square and shorter than that of the one shown in the second square. In this second stage, the boy is perplexed and does not think he knows the right answer of which he is ignorant. Being aware of his own ignorance, the boy gladly takes on the burden of the search since successful completion of the quest will aid in ridding him of his perplexity. Socrates contrasts the slave boy and Meno: when Meno’s second attempt at finding the essence of “human excellence” (arete) failed earlier in the dialogue, Meno’s own words are said to him; but Meno, knowing “no shame” in his “forgetfulness” of himself, resorts to mocking and threatening Socrates. (This resort to violence is characteristic of those lacking in self-knowledge.) One cannot begin the quest to know when one thinks one already knows. The “conversion” of our thinking occurs when one reaches an aporia or “a dead end” and falls into a state of perplexity, becomes aware of one’s own ignorance, and experiences an erotic need for knowledge to be rid of the perplexity. The quest for knowledge results in an “opinion”: a “justified true belief”. The human condition is to dwell within and between the realm of thought and opinion, in the very centre of the Divided Line.

Stage Three: The boy remains in his perplexity and his next answer is “The length will be three feet”. The size then becomes 9 square feet when the boy’s answer is shown to him by Socrates as he draws the figure shown on the left.

Stage Four: Socrates draws the diagonals inside the four squares. Each diagonal cuts each of the squares in half and each diagonal is equal. The space (4 halves of the small squares) is the correct answer. It is the diagonal of the squares that gives the correct answer. The diagonals are “inexpressible lengths” since they are what we call “irrational numbers”. We note that the square drawn by Socrates is the same square that is present in the intersection of two cones and their gyres that were shown previously. The diagonal is the hypotenuse of the right-angled triangle that is formed: a2 + b2 = c2. Pythagoras is said to have offered a sacrifice to the gods upon this discovery for to him it showed the possibility of true, direct encounters with the divine and true possibilities for redemption from the human condition, the movement from thought and opinion to gnosis.

For the Pythagoreans, human beings were considered “irrational numbers”. They believed that this best described that ‘perfect imperfection’ that is human being, that “work” that was “perfect” in its incompleteness. This view was in contrast to the Sophist Protagoras’ statement that “Man is the measure of all things”, for how could something incomplete be the measure of anything. The irrational number (1 + √5)/2 approximately equal to 1.618) was , for the Pythagoreans, a mathematical statement illustrating the relation of the human to the divine. It is the ratio of a line segment cut into two pieces of different lengths such that the ratio of the whole segment to that of the longer segment is equal to the ratio of the longer segment to that of the shorter segment. This is the principle of harmonics on stringed musical instruments, but this principle also operated, the Pythagoreans believed, on the moral/ethical level also. “The music of the spheres” which is the world of these harmonic vibrations and relations provided for the Pythagoreans principles for human action or what the Greeks called sophrosyne, what we understand as ‘moderation’. The Philosopher’s Stone (or Rock), long a subject of myth and narrative, is the human soul itself. A statement attributed to Pythagoras is: “The soul is a number which moves of itself and contains the number 4.” One could also add that the human soul contains the number 3 which was the principle of movement (Time) for it consists of three parts (past, present, and future), thus giving us 4 + 3 = 7, the 4 being the res extensa of material in space. 7 was a sacred number for the Pythagoreans for it was both the ’embodied soul’ of the human being and the ‘Embodied Soul’ of the Divine, the human soul being the mirroring microcosm of the macrocosm.

In terms of present day algebra, letting the length of the shorter segment be one unit and the length of the longer segment be x units gives rise to the equation (x + 1)/x = x/1; this may be rearranged to form the quadratic equation x2 – x – 1 = 0, for which the positive solution is x = (1 + √5)/2) or the golden ratio. If we conceive of the 0 as non-Being, we can conceive of the distinction between modern day algebra and the Greek understanding of number. For the Pythagoreans, the whole is the 1 and the part is some other number than the 1. It should be noted that the Greeks rejected Babylonian (Indian) algebra and algebra in general as being ‘unnatural’ due to its abstractness, and they had a much different conception of number than we have today. (The German philosopher Heidegger in his critique of Plato’s doctrine of the truth and of the Good shown in Bk VII of Republic, for example, deals with the Good as an abstract concept thus performing an exsanguination on the political life and the justice that is shown in the concrete details of Bk VI of Republic. Is this the reason that Heidegger failed to recognize the Great Beast that was Nazi Germany in 1933? and was it this unwillingness to recognize this fact that allowed this philosopher to tragically succumb to that Beast?)

The Pythagoreans and their geometry are not how we look upon mathematics and number today. Our view of number is dominated by algebraic calculation. The Pythagoreans were viewed as a religious cult even in their own day. For them, the practice of geometry was no different than a form of prayer or piety, of contemplation and reflection. The Greek philosopher Aristotle called his former teacher, the Greek philosopher Plato, a “pure Pythagorean”.

This “pure Pythagoreanism” is demonstrated in Plato’s illustration of the Divided Line which is none other than an application of the golden mean or ratio to all the things that are and how we apprehend or behold them. I am going to provide a detailed example from Plato’s Republic because I believe it is crucial to our understanding of the thinking that has occurred in the West.

At Republic, Book VI, 508B-C, Plato makes an analogy between the role of the sun, whose light gives us our vision to see and the visible things to be seen and the role of the Good in that seeing. The sun rules over our vision and the things we see. The eye of seeing must have an element that is “sun-like” in order that the seeing and the light of the sun be commensurate with each other. Vision does not see itself just as hearing does not hear itself. No sensing, no desiring, no willing, no loving, no fearing, no opining, no reasoning can ever make itself its own object. The Good, to which the light of the sun is analogous, rules over our knowledge and the (real) being of the objects of our knowledge (the forms/ eidos), the offspring of the ideas or that which brings the visible things to appearance and, thus, to presence or being and also over the things that the light of the sun gives to vision:

“This, then, you must understand that I meant by the offspring of the good that which the good begot to stand in a proportion with itself: as the good is in the intelligible region with respect to intelligence (DE) and to that which is intellected [CD], so the sun is (light) in the visible world to vision [BC] and what is seen [AB].”

| E. The Idea of the Good: Agathon, Gnosis “…what provides the truth to the things known and gives the power to the one who knows, is the idea of the good. And, as the cause of the knowledge and truth, you can understand it to be a thing known; but, as fair as these two are—knowledge and truth—if you believe that it is something different from them and still fairer than they, your belief will be right.” (508e – 509a) | |

| D. Ideas: Begotten from the Good and are the source of the Good’s presence (parousia) in that which is not the Good. The Good is seen as “the father” whose seeds (ἰδέαι) are given to the receptacle or womb of the mother (space) to bring about the offspring that is the world of AE (time). The realm of AE is the realm of the Necessary. (Dialogue Timaeus 50-52 which occurs the following morning after the night of Republic) | D. Intellection (Noesis): Noesis is often translated by “Mind”, but “Spirit” might be a better translation. Knowledge (γνῶσις, νοούμενα) intellection, the objects of “reason” (Logoi) (νόησις, ἰδέαι, ἐπιστήμην). “Knowledge” is permanent and not subject to change as is “opinion” whether “true” or “false” opinion. Opinions develop from the pre-determined seeing which is the under-standing of the essence of things. |

| C. Forms (Eide): Begotten from the Ideas (ἰδέαι) . They give presence to things through their “outward appearance” (ousia). There is no-thing without thought; there is no thought without things. Human being is essential for Being. Being needs human being. “And would you also be willing,” I said, “to say that with respect to truth or lack of it, as the opinable is distinguished from the knowable, so the likeness is distinguished from that of which it is the likeness?” | C. Thought (Genus) Dianoia is that thought that unifies into a “one” and determines a thing’s essence. The eidos of a tree, the outward appearance of a tree, is the “treeness”, its essence, in which it participates. We are able to apprehend this outward appearance of the physical thing through the “forms” or eide in which they participate. Understanding, hypothesis (διανόια). The “hypothesis” is the “standing under” of the seeing that is thrown forward, the under-standing, the ground. |

| B. The physical things that we see/perceive with our senses (ὁρώμενα, ὁμοιωθὲν) | B. Trust, confidence, belief (πίστις) opinion, “justified true beliefs” (δόξα, νοῦν). Opinion is not stable and subject to change. The changing of the opinions that predominate in a community is what is understood as “revolution”. “Then in the other segment put that of which this first is the likeness—the animals around us, and everything that grows, and the whole class of artifacts.” |

| A. Eikasia Images Eikones: Likenesses, images, shadows, imitations, our vision (ὄψις, ὁμοιωθὲν). The “icons” or images that we form of the things that are. The statues of Dedalus which are said to run away unless they are tied down (opinion). It is the logoi which ‘ties things down’. | A. Imagination (Eikasia): The representational thought which is done in images. Our narratives, myths and that language which forms our collective discourse (rhetoric). Conjectures, images, (εἰκασία). The image of a thing of which the image is an image are things belonging to eikasia. We are “reminded” of the original by the image. “Now, in terms of relative clarity and obscurity, you’ll have one segment in the visible part for images. I mean by images first shadows, then appearances produced in water and in all close-grained, smooth, bright things, and everything of the sort, if you understand.” |

The whole Line may be outlined into five sections: a)The Idea of the Good : to the whole of AE; b) the Idea of the Good : DE; c) DE : CD; d) BC = CD; e) BC : AB. The whole line itself (AE) is the Good’s embrasure of both Being and Becoming. The Good is beyond Being and Becoming (i.e., space and time), and there is an abyss separating the Necessary from the Good. Within the Divided Line, that which is “intellected” (CD) is equal to (or the Same i.e., a One) as that which is illuminated by the light of the sun in the world of vision (BC). Being and Becoming require the being-in-the-world or participation of human beings; B = C. That which is “intellected” (the schema) is that which comes into being or can come into being through imagination and representational thinking, through images (or the assigning of numbers or signs to images as is done in geometry or algebra) or through the logoi or words of narrative and myth as well as rhetoric. This representational thinking in images is what we call “experience”. Every thought and all of our thinking is a product of or “re-collection” (anamnesis) from experience: we have to first experience before we can “re-collect” that which we have experienced. This re-collection is what is referred to as dianoia. This may account for the confusion between the concepts of eidos and ἰδέαι in the interpretations of Plato. The ἰδέαι is number as the Greeks understood them; the eidos is number as we understand them: the two concepts represent the “double” nature of thinking and the distinction between thought and Intellection. The ἰδέαι begets the eidos and like a father to his offspring, they are akin to each other and yet separate. Intellection is akin to thinking yet separate from thinking.

Eide + logoi + idea: the things seen and heard require a “third”. “Light” is the “third” for seeing as well as what we understand as “air” for hearing. “The outward appearances of the things” + “the light” which “unconceals” them + the idea as that which begets both the outward appearance and the unconcealment. The Sun is an image of the Good in the realm of Becoming because “it gives” lavishly and “yokes together” that which sees and that which can be seen. Neither sight itself nor that in which it comes to be (the “eye”) are the sun itself. The sun is not sight itself but its “cause” (aitia understood as “responsible for”). The sun is the offspring of the Idea of the Good begot in a proportion with itself: The Good = 1 : the Sun the square root of 5/2 (1 + √5)/2). The two together give the Divine Ratio. 508 c. “As the Good is in the intelligible region with respect to intelligence and what is intellected, so the sun is in the visible region with respect to sight and what is seen”. (The Sun = Time; and from it things come to be and pass away. “Time is the moving image of eternity” i.e., the Sun is Time which is the movement of that which is permanent or ‘eternal’, i.e., The Good. “Faith is the experience that the intelligence is illuminated by Love.” Pistis trust or faith is the “experience”, the “contact with reality” that the intelligence realizes when it is given the light of Love or the Good. This truth aletheia is proportional to the truth aletheia which is the unconcealment of things of the senses in the physical realm when revealed by the Sun i.e., the beauty of the world.)

The soul, “when it fixes itself on that which is illuminated by truth” and that which is, “intellects”, knows, and appears to possess intelligence (gnosis). When it fixes itself on that which is mixed with darkness, on coming into being and passing away, it opines and is dimmed. What provides truth to the things known and gives illumination or enlightenment to the one who knows is the Idea of the Good. The Idea of the Good is responsible for (the “cause of”) knowledge and truth. It is responsible for the beautiful and that which makes things beautiful. But the Good itself is beyond these. It is the Good which provides “the truth” to the things known, truth understood as aletheia or unconcealment. As the eye and that which is seen is not the sun, so knowledge and the things known are not the Good itself i.e., those things that are “goods” for us. When Glaucon equates the Good with “pleasure”, Socrates tells him to “Hush” for he is uttering a “blasphemy”. It is clear that what is being spoken about here is a “religious phenomenon”.

In the “double” manner of “seeing”, the soul uses images of the things that are imitated to make “hypothesis”, “to place under” its suppositions; and from this placing under makes its way to a “completion”, an end (telos). This is the world of the scientists and artisans, the technites, the world of “formation”, the “making” and “knowing” that is technology. This is a movement downwards. The movement upwards “makes its way to a beginning”, “a starting point”, a “principle”, a “cause” by means of the eidos and “forms” themselves i.e., it begins from the beauty of the “outward appearances of the things”. Beginning from the assumed hypotheses, the geometers end consistently at the object towards which their investigation was directed. “The other segment of the intelligible” is grasped by “dialectic” (the speeches or dialogues/conversations with others; the discussion among friends; the two or three gathered together). The hypotheses are “steppingstones and springboards” in order to reach the “beginning” which is the whole (the Good). The “argument” that has grasped the good is the argument that depends on that which depends on this beginning: it descends to an end (with the grasping of the good) using the eide throughout “making no use of anything sensed in any way, but using the eide themselves, going through forms to forms, it ends in forms, too.” 512 b (This is the descent described in the allegory of the Cave.)

Using Euclid’s Elements, we can examine the geometry inherent in the Divided Line and come to see how it is related to the notion of the golden ratio. Notice that the Idea of the Good is left out of the calculations conducted here.

“Let the division be made according to the prescription:

(A + B) : (C + D) : : A : B : : C : D.

From (A + B) : (C + D) : : C : D follows (Euclid V, 16)

(1) (A + B) : :C : (C + D) : D. From A :B : : C: D follows (Euclid V. 18)

(2) (A + B) : B : : ( C + D) : D. Therefore (Euclid V, 11)

(3) (A + B) : C : : (A + B) :B and consequently (Euclid V, 9)

4) C= B.

Since C = B, the inequality in length of the “intelligible” and “visible” subsections depends only on the sizes of A (Imagination) and D (Intellection). If, then, A : B : : B : D or A : C : : C : D, A : D is in the duplicate ratio of either A : B or C : D (Euclid V, Def. 9). This expresses in mathematical terms the relation of the power of “dialectic“, the discursive conversations between friends, to the power of eikasia, the individual and collective imaginations of human beings. (To put it in modern terms and our relations to our thought and actions, it is the difference between the face-to-face conversations among friends and the collective conversations of social media chat groups.) If we imagine the Divided Line as two intersecting gyres, we may be able to see how this ‘double’ thinking, learning and seeing is possible. Thinking can be either an ascent into the realm of ideas aided by the beauty of the outward appearances of things (eidos) and the dialectical conversation of friends, or thinking can be a descent into the realm of material things using the imagination (eikasia) and the rational applications of the relations of force (Necessity), our common understanding of thinking.

At the end of Book VI of the Republic (509D-513E), Plato describes the visible world of perceived physical objects and the images we make of them (what we call representational thinking). The sun, he said, not only provides the visibility of the objects, but also generates them and is the source of their growth and nurture. This visible world is what we call Nature, physis, the physical world in which we dwell.

Beyond and within this visible or sensible world lies an intelligible world. The intelligible world is illuminated by “the Good”, just as the visible world is illuminated by the sun. The sun is the image of the Good in this world. The Good provides growth and nurture in the realm of Spirit, or that which is Intellected. For Socrates and Plato, the world is experienced as good, and our experience of life should be one of gratitude. The world is not to be experienced as a “dualism”, for a world without human beings is no longer a “world” and human beings without a world are no longer human beings.

The division of Plato’s Line between Visible and Intelligible appears to be a divide between the Material and the Ideal or the abstract. This appearance became the foundation of most Dualisms, particularly the Cartesian dualism of subject-object which is the foundation of modern knowledge and science. To see it as such a dualism overlooks the fact that the whole is One and the One is the Good. Plato is said to have coined the word “idea” (ἰδέα), using it to show that the outward appearances of things (the Greek word for shape or form εἶδος) are the offspring of the “ideas”, and are akin to the ideas, but they are not the ideas themselves. They are the Same, but not Identical. The word idea derives from the Greek “to have seen”, and this having seen a priori as it were, determines how the things will appear to the eye which is “sun-like” i.e., it shares something in common with the light itself and with the sun itself. This commonality is what we mean by our understanding and experience.

The upper half of the Divided Line is usually called Intelligible as distinguished from the Visible, meaning that it is “seen” and ‘has been seen’ by the mind (510E), by the Greek Nous (νοῦς), rather than by the eye. Whether we translate nous as ‘mind’ or ‘spirit’ has been a topic of controversy in academic circles for many centuries. The translation as ‘mind’ seems to carry a great deal of baggage from our understanding of human beings as the animale rationale.

In modern English, the word “knowledge” derives from “to be cognizant of”, “to be conscious of”, or “to be acquainted with”; the other stems from “to have seen” (See endnote). The first is the cognate of English “know” e.g., Greek gnosis (γνῶσις), meaning knowledge as a direct contact with or an experience of something. For knowledge, the Greeks also used epistέme (ἐπιστήμη), the root for our word epistemology. Gnosis and episteme are two very different concepts: gnosis can be understood as direct contact with, while episteme is more related to the results of “theoretical knowledge” which are abstract and reside in the realm of opinion.

This stem of “to have seen” is what is rooted in the idea of “re-collection” with the associated meanings of “collecting” and “assembling” that are related to the Greek understanding of logos. Logos is commonly translated as “reason” and this has given it its connections to ‘logic’ and ‘logistics’ as the ‘rational’ and ultimately to human beings being defined as the animale rationale, the “rational animal” by the Latins rather than the Greek zoon logon echon, or “that animal that is capable of discursive speech”. Discursive speech, dialectic, and logos in general are not what we understand by “reason” only. “Intellection” as it is understood in Plato’s Divided Line is not merely the principle of cause and effect and the principle of contradiction.

In Republic, Book VI (507C), Plato describes the two classes of things: those that can be seen but not thought, and those that can be thought but not seen. The things that are seen are the many particulars that are the offspring of the eidos, while the “ones” are the ideai which are the offspring of the Good. As one descends from the Good, the clarity of things becomes dimmer until they are finally merely ‘shadows’, deprived of the light of truth because of their greater distance from the Good. As there are many particular examples of human “competence” or “excellence” (arete), there is the one competence or excellence that all of these particular examples participate in. This “one” is the idea and the idea is itself an offspring of the Good, the original One. The idea is the ‘measure’ of the thing and how we come to “measure up” the thing to its idea. (Our notion of ideal derives from this.) It is through this measuring that the thing gets its eidos or its “outward appearance”; and in its appearance, comes to presence and to being for us.

At Republic, Book VI, 508B-C, Plato makes an analogy between the role of the sun, whose light gives us our vision to see (ὄψις) and the visible things to be seen (ὁρώμενα) and the role of the Good (τἀγαθὸν). The sun “rules over” our vision and the things we see since it provides the light which brings the things to ‘unconcealment’ (aletheia or truth). The Good “rules over” our knowledge and the (real) objects of our knowledge (the forms, the ideas) since it provides the truth in this realm:

“This, then, you must understand that I meant by the offspring of the good which the good begot to stand in a proportion with itself: as the good is in the intelligible region to intellection [DE] and the objects of intellection [CD], so is this (the sun) in the visible world to vision [AB] and the objects of vision [BC].” As the sun gives life and being to the physical things of the world, so the Good gives life and being to the sun as well as to the things of the ‘spiritual’ or the realm of the ‘intellect’. That which the Good begot is brought to a stand (comes to permanence) in a proportion with itself. These proportions are present in the triangles of the geometers.

At 509D-510A, Plato describes the line as divided into two sections that are not the same (ἄνισα) length. Most modern versions represent the Intelligible section as larger than the Visible. But there are strong reasons to think that for Plato the Intelligible is to the Visible (with its many concrete particulars) as the one is to the many. The Whole is greater than the parts. The part is not an expansion of the Whole but the withdrawal of the Whole to allow the part to be as separate from itself, or rather, to appear as something separate from itself since the part remains within the Whole. In this separation from the Whole, the part loses that clarity that it has and had in its participation in the Whole. (It is comparable to the square spoken of earlier from the Meno dialogue: the original square withdraws to allow the “double” to be.)

When Plato equates B to C, we can understand that the physical section limits the intelligible section, and vice versa. We cannot have what we understand as ‘experience’ without body, and we cannot have body without intellect. We place the intelligible section above the physical section for the simple reason that the head is above the feet.

Plato then further divides each of the Intelligible and the Visible sections into two. He argues that the new divisions are in the same ratio as the fundamental division. The Whole, not being capable of being ascribed an “image” by a line, is to the entire line itself as the ratio of the Good is to the whole of Creation. The whole of Creation is an “embodied Soul”, just as human being is an “embodied soul” and is a microcosm of the Creation. Just as the Good withdraws to allow Creation to be, Creation withdraws to allow the human being to be.

Later, at 511D-E, Plato summarizes the four sections of the Divided Line:

“You have made a most adequate exposition,” I said. “And, along with me, take these four affections arising in the soul in relation to the four segments: intellection in relation to the highest one, and thought in relation to the second; to the third assign trust, and to the last imagination. Arrange them in a proportion, and believe that as the segments to which they correspond participate in truth, so they participate in clarity.”

We can collect the various terms that Plato has used to describe the components of his Divided Line. Some terms are ontological, describing the contents of the four sections of the Divided Line and of our being-in-the-world; some are epistemological, describing how it is that we know those contents. There is, however, no separation between the two. Notice that there is a distinction between “right opinion” and “knowledge”. Our human condition is to stand between thought and opinion. “Right opinion” is temporary, historical knowledge and thus subject to change, while “knowledge” itself is permanent. The idea of the Good is responsible for all knowledge and truth. Such knowledge is given to us by the geometrical “forms” or the eide which bring forward the outward appearances of the things that give them their presence and for which the light of the sun is necessary. “Knowledge” as episteme and knowledge as gnosis are also distinguished.

By insisting that the ratio or proportion of the division of the visibles (AB:BC) and the division of the intelligibles (CD:DE) are in the same ratio or proportion as the visibles to the intelligibles (AC:CE), Plato has made the section B = C. Plato at one point identifies the contents of these two sections. He says (510B) that in CD the soul is compelled to investigate, by treating as images, the things imitated in the former division (BC):

“Like this: in one part of it a soul, using as images the things that were previously imitated (BC), is compelled to investigate on the basis of hypotheses and makes its way not to a beginning but to an end (AB); while in the other part it makes its way to a beginning that is free from hypotheses (DE); starting out from hypothesis and without the images used in the other part, by means of forms (idea) themselves it makes its inquiry through them.” (CD)

Plato distinguishes two methods here, and it emphasizes the “double” nature of how knowledge is to be sought and how learning is to be carried out. The first (the method of the mathematician or scientist and what determines our dominant method today) starts with assumptions, suppositions or hypotheses (ὑποθέσεων) – Aristotle called them axioms – and proceeds to a conclusion (τελευτήν) which remains dependent on the hypotheses or axioms, which again, are presumed truths. We call this the ‘deductive method” and it results in the obtaining of that knowledge that we call episteme. This obtaining or end result is the descent in the manner of the ‘double’ thinking that we have been speaking about; we descend from the general to the particular. This type of thinking also involves the ‘competence’ in various technai or techniques that are used to bring about a ‘finished work’ that involve some ‘good’ of some type. It is the ‘knowing one’s way about or in something’ that brings about the ‘production’ or ‘making’ of some thing that we, too, call knowledge be it shoemaking and the pair of shoes or the making of artificial intelligence. The end result, the ‘work’, provides some ‘good’ for us in its potential use.

In the second manner, the “dialectician” or philosopher advances from assumptions to a beginning or first principle (ἀρχὴν) that transcends the hypotheses (ἀνυπόθετον), relying on ideas only and progressing systematically through the ideas. The ideas or noeton are products of the ‘mind’ or ‘spirit’(nous) that the mind or spirit is able to apprehend and comprehend due to the intercession of the Good as an intermediary, holding or yoking itself and the soul of the human being in a relationship of kinship or friendship. The ideas are used as stepping stones or springboards in order to advance towards a beginning that is the whole. The ‘step’ or ‘spring’ forward is required to go beyond the kind of thinking that involves a descent. The beginning or first principle is the Good and this is the journey to the Good or the ascent of thinking towards the Good itself. In his Seventh Letter, Plato uses the metaphor of ‘fire catching fire’ to describe this ascent.

Plato claims that the dialectical “method” (and it is questionable what this “method” is exactly), which again must be understood as the conversations between friends, between a learner and teacher for example, is more holistic and capable of reaching a higher form of knowledge (gnosis) than that which is to be achieved through ‘theoretical knowledge’ or episteme. This possibility of gnosis is related to the Pythagorean notion that the eternal soul has “seen” all these truths in past lives (anamnesis) in its journey across the heavens with the chariots of the gods. (Phaedrus 244a – 257 b)

Plato does not identify the Good with material things or with the ideas and forms. Again, these are in the realm of Necessity; Necessity is the paradigm or the divine pattern. The Good is responsible for the creative act that generates the ideas and the forms (identified as “cause” in the Bloom translation of Republic used here). The ideas and the forms are ‘indebted to’ the Good for their being and from them emerge truth, justice, and arete or the virtues of things and beings.

If we put the mathematical statement of the golden ratio or the divine proportion into the illustration (1 + √5)/ 2), the 1 is the Good, or the whole of things, and the “offspring of the Good” (the “production of knowledge” (BC + CD) is the √5 which is then divided by 2 (the whole of creation: Becoming, plus Being, plus the Good or the Divine), then we can comprehend the example of the Divided Line in a Greek rather than a Cartesian manner. Plato is attempting to resolve the problem of the One and the Many here.

The ratio or proportion of the division of the visibles (AB : BC) and the division of the intelligibles (CD : DE) are in the same ratio or proportion as the visibles to the intelligibles (AC : CE). Plato has made B = C, and Plato identifies the contents of these two sections. The philosopher:

“does not lose the keenness of his passionate love nor cease from it before he grasps the nature itself of each thing that is with the part of the soul fit to grasp a thing of that sort; and it is the part akin to it that is fit. And once near it and coupled with what really is, having begotten intelligence and truth, he knows and lives truly, is nourished and so ceases from his labour pains, but not before.” (490 b)

The terminology used is that of love, procreation and childbirth. Socrates ironically refers to himself as a “mid-wife” assisting in the birth of intelligence and truth. The passage quoted above shows the inadequacy of translating the Greek nous as “intellection”, for the concept seems to be much broader than something associated with only the mind or intellect. The soul is a tripartite entity, and in its grasping of the things that are must have a part of itself that is “akin” to that which is being grasped. The various parts of the soul are that which engages in the various aspects of being-in-the-world. This engagement is an erotic one in the sense that human beings ‘need’ this engagement in order to be fully human beings. The separation of thought and practice is not possible or ‘real’. In the Divided Line, the gnosis that comes to presence through nous is beyond thought and what we traditionally understand by thinking.

The city’s outline, or the community in which human beings dwell, should be drawn by the painters who use the divine pattern or paradigm which is revealed by Necessity(500 e). In the social and political realm, the individual must first experience the logoi in order to become balanced in the soul as far as that is possible. This experience, this speech with others, will provide moderation (sophrosyne), justice (recognition of that which is due to other human beings) and proper virtue (phronesis) which is ‘wise judgement’.

Socrates says (510B) that in CD the soul is compelled to investigate by treating as images the things imitated in the former division (BC). In (BC), the things imitated are the ‘shadows’ of the things as they really are. These are the realms of ‘trust’ and ‘belief’ (pistis) and of understanding or how we come to be in our world. Our understanding derives from our experience and it is based on what we call and believe to be “true opinion”, ortho doxa.

There is no “subject/object” separation of realms here, no abstractions or formulae created by the human mind only (the intelligence and that which is intellected), but rather the mathematical description or statement of the beauty of the world. In the Divided Line, one sees three applications of the golden ratio: The Good, the Intelligible, and the Sensible or Visual i.e., the Good in relation to the whole line, The Good in relation to the Intelligible, and the Intelligible in relation to the Visible. (It is from this that I understand the statement of the French philosopher Simone Weil: “Faith is the experience that the intelligence is illuminated by Love.” Love is the light, that which is given to us which illuminates the things of the intelligence and the things of the world, what we “experience”. This illumination is what is called Truth for it reveals and unconceals things. There is a concrete tripartite unity of Goodness, Beauty and Truth. The word ‘faith’ in Weil’s statement could also be rendered by ‘trust’ or pistis.)

The Golden Ratio

This tripartite yoking of the sensible to the intelligible and to the Good corresponds to what Plato says is the tripartite being of the human soul and the tripartite Being of the God who is the Good. The human being in its being is a microcosm of the Whole or of the macrocosm. The unconcealment of the visible world through light conceived as truth (aletheia) is prior to any conception of truth that considers “correspondence” or “agreement” or “correctness” as interpretations of truth. (See William Blake’s lines in “Auguries of Innocence”: “God appears and God is Light/ To those poor souls that dwell in night/ But does the human form display/ To those who dwell in realms of day.”)

The golden ratio occurs in many mathematical contexts today. It is the limit of the ratios of consecutive terms of the Fibonacci number sequence 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13…, in which each term beyond the second is the sum of the previous two, and it is also the value of the most basic of continued fractions, namely 1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 +⋯. (Encyclopedia Britannica) In modern mathematics, the golden ratio occurs in the description of fractals, figures that exhibit self-similarity and play an important role in the study of chaos and dynamical systems. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

One of the questions raised here is: do we have number after the experience of the physical, objective world or do we have number prior to it and have the physical world because of number? The original meaning of the Greek word mathemata is “what can be learned and what can be taught”. What can be learned and what can be taught are those things that have been brought to presence through language and measured in their form or outward appearance through number. Our understanding of number is what the Greeks called arithmos, “arithmetic”, that which can be counted and that which can be “counted on”. These numbers begin at 4.

The principles of the golden or divine ratio are to be seen in the statue of the Doryphoros seen here. The statue of the Doryphoros, or the Spear Bearer, is around the mid -5th century BCE. Its maker, Polycleitus, wrote that the purpose or end of art was to achieve to kallos, “the beautiful” and to eu (the perfect, the complete, or the good) in the work and of the work. The secret of achieving to kallos and to eu lay in the mastery of symmetria, the perfect “commensurability” of all parts of the statue to one another and to the whole. Some scholars relate the ratios of the statue to the shapes of the letters of the Greek alphabet. We can understand why this would be the case from what has been previously said here. Writing is mimesis, a copying, imaging and ‘playfulness’. There is ‘playfulness’ in the mathematical arts as their figures are images. but because they “imitate”, they are also unreliable.

The Egyptian connection to the geometry of the Pythagoreans is of the utmost importance to Western civilization and also to what we are discussing here. The Pythagorean theorem, a2 + b2 = c2, is the formula whereby two incommensurate things are brought into proportion, relation, or harmony with one another and are thus unified and made the Same i.e., symmetria. What is the incommensurate? Human beings and all else that is not human being are incommensurate. For the Pythagoreans, human beings are irrational numbers. Pi, the circumference of a circle, is an irrational number, and the creation itself is an irrational number because it was viewed as circular or spherical and Pi represents its limit or circumference . The Pythagoreans did not see the earth or the world as “flat”; it was spherical. The human being as an irrational number is a microcosm of the whole of the creation (or what is called Nature) itself.

The meanings of the word “incommensurate” are extremely important here. It is said to be “a false belief or opinion of something or someone; the matter or residue that settles to the bottom of a liquid (the dregs); the state of being isolated, kept apart, or withdrawn into solitude.” An incommensurate is something that does not fit. Pythagorean geometry was the attempt to overcome all of these “incommensurables” in human existence, an attempt to make them fit or to show that they are fitted, to yoke them together. “Fittedness” is what the Greeks understood by “justice”; and the concept of justice was tied in with “fairness” (beauty), what was due to someone or something, what was suitable or apt for that human being or that thing. To render another human being their due was a ‘beautiful’ action. The beginning of this rendering is the initial recognition of the otherness of human beings.

From their geometry, the Pythagoreans were said to have invented music based on the relations of the various notes around a mean i.e., the length of the string and how it is divided into suitable lengths as to allow a harmonic to be heard when it was plucked. This harmony found in music by the Pythagoreans was looked for in all human relations between themselves and the things that are, including other human beings. This harmony was the relation of ‘friendship’ established between two incommensurate entities; in human relations, that which makes us ‘in tune’ with one another. It was a reflection in the microcosm of the ‘music of the spheres’.

When we speak of the “production of knowledge” in the modern sense, we are speaking of technology and the finished products that technology brings forth. “Knowledge’ is the finished or completed ‘work’ that is the result of the “production” that technology ‘brings forth’. Technology comes from two Greek words: Techne, which means ‘knowing’ or ‘knowing one’s way about or in something’ in such a way that one can ‘produce’ knowledge, the ‘work’, and begin the making of something; and logos which is that which makes this knowledge at all possible. We confuse the things or works of technology, the produce of technology, with technology itself. Technology is a way of being in the world. This confusion is not surprising given the origin of the word. The word is not to be found in Greek but comes to be around the mid-15th century.

Leonardo da Vinci was a prolific user of the Divine Proportion in his painting, engineering works, and illustrations. The publication of De Divina Proportione (1509; Of the Divine Proportion), written by the Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli and illustrated by Leonardo is one example. Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” is what is called in Greek an eikon from which our word “icon” is derived. The word means “a painting, a sculpture, an image, a drawing, a reflection in a mirror—any likeness.” The Vitruvian Man is intended to be viewed behind the head as a reflection in a mirror. The notes to the drawing are written backwards. The dimensions of the figure are written in ratios: the length of the arms equals the height of the body, etc. so that one gets a square. The arms and legs of the figure are ‘doubled’, one set touching the circumference of the circle (but notice they remain within the boundary of the square), and one set completely bounded within the square. This is a pictorial illustration of Plato’s Divided Line. The circle is AE while the square is AD. The Vitruvian Man is similar to the Greek Doryphoros as the “perfection” is the result of the perfect ratios. The attempt here is nothing short of an attempt to “square the circle!” (See Republic 509e-510a).

“These things themselves that they mold and draw, of which there are shadows and images in water, they now use as images, seeking to see those things themselves, that one can see in no other way than with thought.” (510e)

Since technology rests upon an understanding of the world as object, an understanding of the world as posable, its mathematics are focused on, for the most part, algebraic calculation which turns its objects into disposables. Whatever beauty an object might have is skipped over (since beauty is not calculable, as much as we may try to do so) in order to demand that the object give its reasons for being as it is. The end of technology is power and will to power, and this is why artificial intelligence is the flowering of technology at its height of its realization. It is a great closing down of thinking for it is, ultimately, an anti-logos. Its roots are nihilism. There is no question that there is some beauty involved in technology, but it is a beauty that is more akin to the handsomeness of Meno, an outward beauty that hides the ugliness and disorder of the soul within. It is a terrible beauty, and it may lead to our extinction as a species.

[i] In modern English the word “knowledge” derives from “to be cognizant of”, “to be conscious of”, or “to be acquainted with”; the other stems from “to have seen.” (This can be related to the names of the “paths of wisdom” on the Tree of Life in an interpretation of the Sefer Yetzirah.) The four sections of the Divided Line correspond to the four worlds of the Sefer Yetzirah: 1. Asiyah: the material world and world of physis or Nature; 2.Yetzirah: the world of formation and making; 3. Beriyah: the world of thought; 4. Atzilut: the world of angels and intellection. The four affections arising in the soul and the four segments of the Divided Line: intellection: ideas; thought: eide; the measure of things: trust (pistis); imagination (eikasia) images. The four affections relate to the four stages of the journey out of the Cave in the allegory of the Cave: the four stages of “truth” as ‘unconcealment’ and the greater clarity achieved at each stage.