The Division Between Love (Eros) and Thinking (Logos)

The most popular site on this blog is Plato’s allegory of the Cave. I am somewhat puzzled by this as the Allegory presents many difficulties as far as its understanding is concerned when it comes to relating it to the ethics and morals required by the Core of the Theory of Knowledge course. The Allegory cannot be properly understood without some knowledge of the Divided Line from Bk VI of Republic .(506c – 511e) Also, one requires some knowledge of Plato’s theory of the tripartite soul that he believed is the essence of human beings. For Plato, the human being was the zoon logon echon, the living being that perdures in logos which is language and number. Later, the Latins would identify the essence of human being as the animale rationale, the “rational animal”, the animal the perdures in “reason”. We shall try to come to some understanding of these definitions here and to show some of the consequences of our choosing the Latinate definition of the essence of human beings.

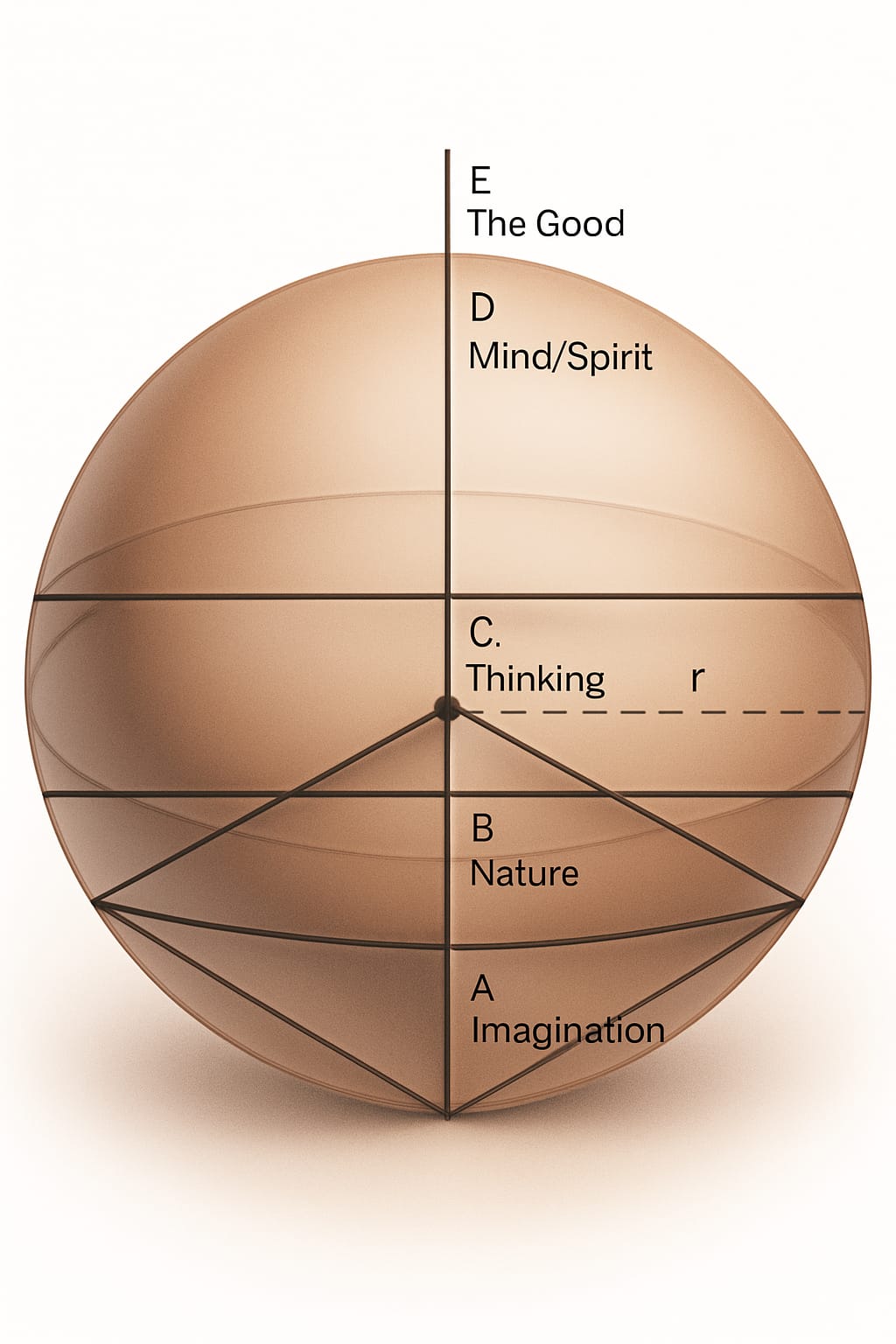

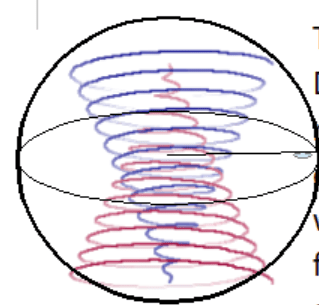

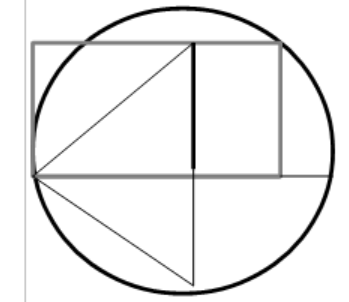

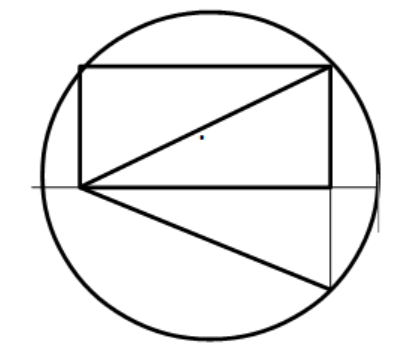

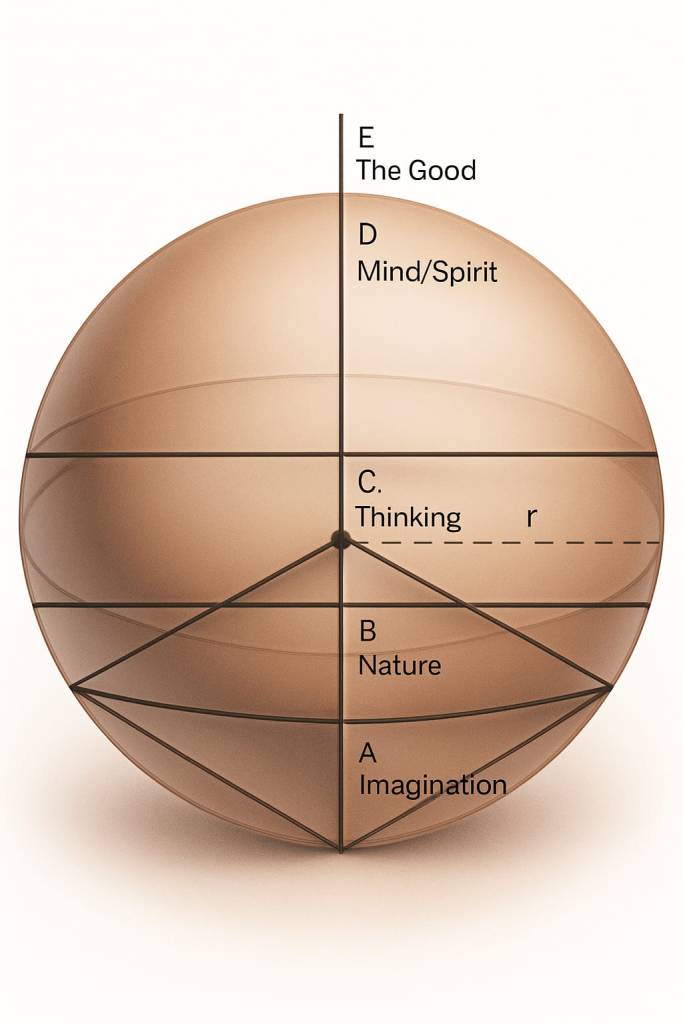

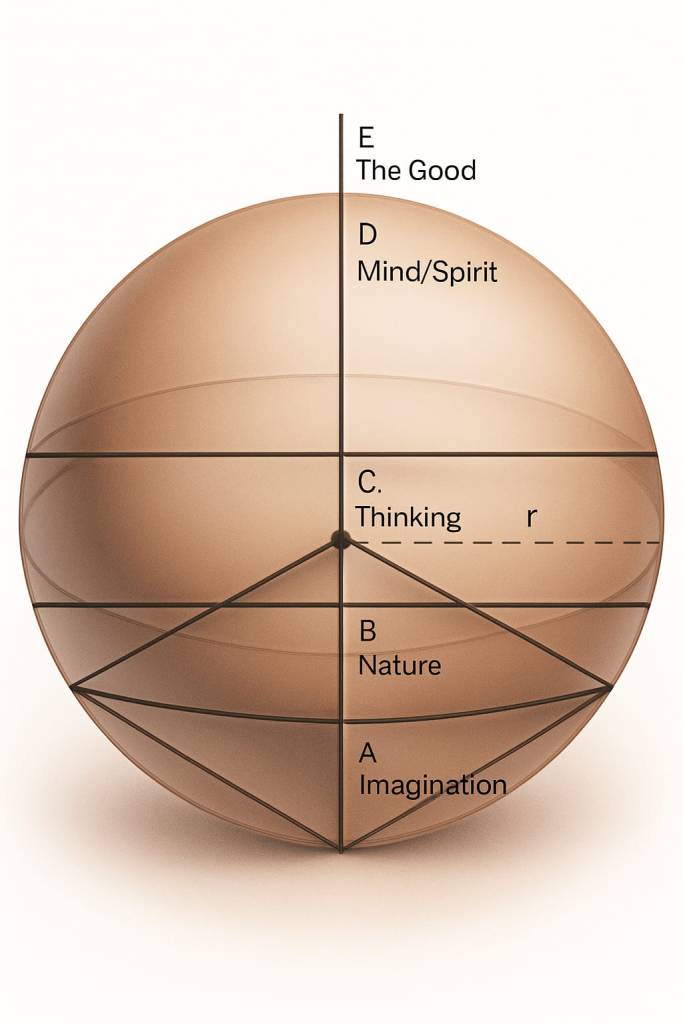

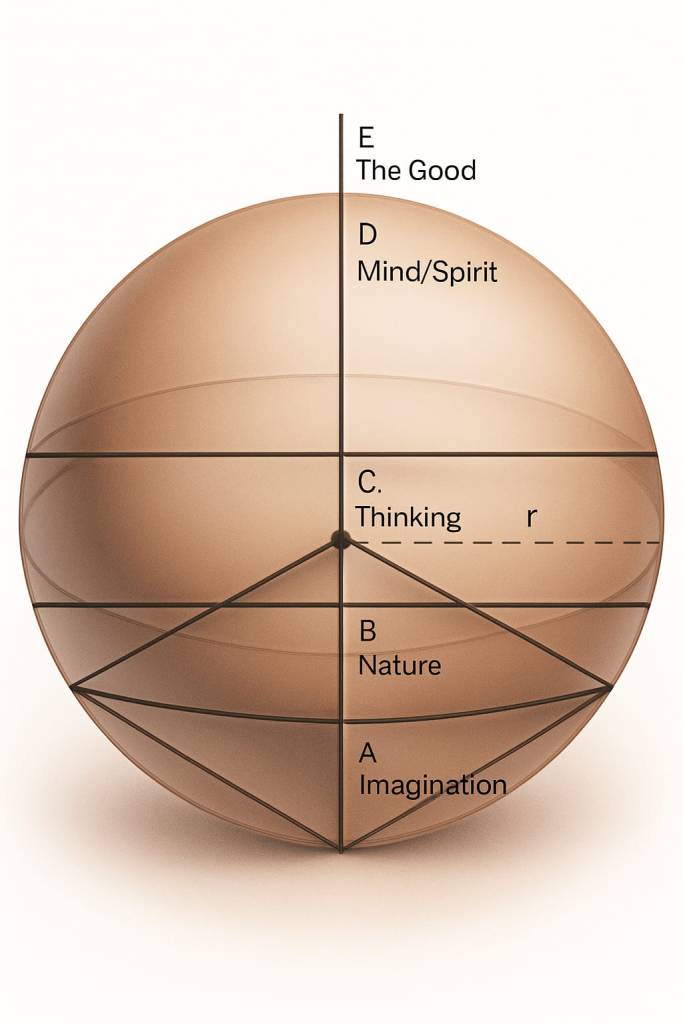

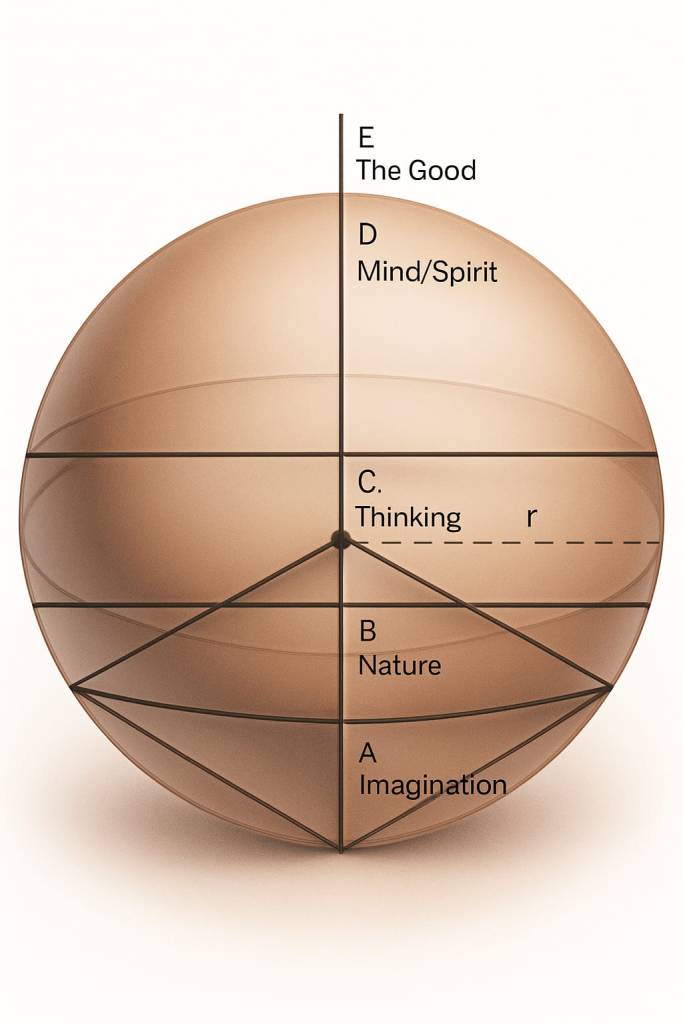

In the illustration above, the human soul’s proper “place” or “site” is at the centre of a sphere that is the being of Time and Space and the created things that are within Time and Space. The sphere itself is constantly in motion. The sphere is what Plato called “the moving image of eternity”, the sempiternal nature of created things.

The realm of “E” is the realm of the Good i.e. the Eternity that encloses or embraces the entirety of the cosmos or creation. The Good begets the Ideas which are in the realm designated by section “D”. The ideas can be approached through the Mind, the Nous, the Spirit, the Intelligence. The Ideas in turn beget the Eidei, the outward appearances of the things that “shine” and which we perceive through the sense of sight because of the “light” that acts as a metaxu or mean between our “eye”, the Sun, and the things that are. This occurs in section “C”. This light, as metaxu, is Eros; the ‘eye’ itself must have a quality that is ‘sun-like’ for there to be a possibility of a commensurable relation between it and the things beyond it.

From this perception occur our axioms and the principles that establish our understanding of the things that are in the world and those beyond it, what the philosopher Kant called the “transcendental imagination”. This perceiving occurs in the “C” section of the Divided Line and establishes our understanding of the things that are. It is the source of our trust, faith and belief in our interpretation of the reality of the things that are that they are as we say and think they are. This we understand as the true. Science, for example, is the theory of the real. “Theory” is a manner or mode of “seeing” and derives from the same root as “theatre”, “the seeing place”. The “theory” is a product or outcome of the “site” or the place from which the seeing is done. Section “C” is equal to section “B” in the Divided Line.

Section “B” is physis or the Cosmos, what we understand as Nature. It is the Cave in Plato’s allegory of the Cave. The Cave is “more real” than the shadows that are “thrown forward” or projected onto the walls of the cave by the artisans and technicians. Even the shadows require light to be produced, but this light is not directly from the Sun. It is a derived or borrowed light (such as that of the Moon, although the light in the cave is due to the fire which has been ignited, presumably, by the artisans and technicians). Fire is a product or derivative of the Sun. In the Cave, there remains a dim presence of the Sun itself but it is ineffectual.

Section “B” = Section “C” in Socrates’ discussion of the Divided Line. It is thought which gives us the things (the techne of the artisans and technicians, “the mind that makes the object” as Kant’s transcendental imagination would have it) and there are no things without thought, whether the thing be natural or artificial or as artefact, as the “work” we produce. The thinking that occurs in Section “C” is that representational thinking that is brought forward or ‘thrown forward’ from Section “A”, the Eikasia or Imagination.

Techne or “know how”, “knowing one’s way about or within something” is but one manner of thinking that the imagination produces. The thinking of the poets is also one manner of thinking that arises from the imagination. Poetic thinking is distinct from the techne of the technicians and still further a different type of thinking than that of the philosophers. This technological thinking of the artisans and technicians occurs on the outer circumference of the sphere, in the realm of the imagination. It is the farthest thinking from that of the philosophers.

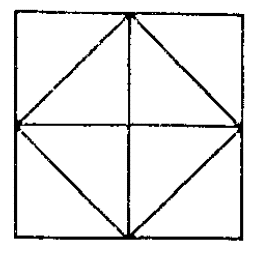

Poetic thinking and techne are the diagonals given in the illustration of the sphere provided here. Both proceed from the “I” in the centre of the sphere which reaches out and “projects” to the circumference of the sphere. The circumference of the sphere is the ‘surface’ phenomenon of things, the deception of their ‘outward’ beauty. It is the thymoeidic part of the soul that is at the root of this projection. The thymoeidic part of the soul deals mostly with will, emotions and feelings, what the Greeks understood as pathos. Our projections are given back to us in the form of a ‘lighted up’ of things. It is eros that does the “lighting up”.

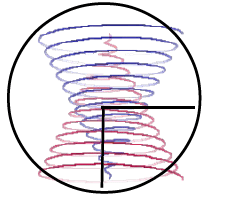

If we look at the statement of Aeschylus that “In war, truth is the first casualty”, we can say that war is evil for all evil requires deception, subterfuge, the hiding from the light. This deception is to be found on the surfaces of phenomenon. That which is thrown forward by the ‘self’ at the centre of the sphere to the circumference through the thymoeides is an ‘irrational number’ in mathematics, what we call pi (the ratio between a circle’s diameter and its circumference), since the two diagonals thrown forward comprise the diameter of the sphere. The movement of the soul outward toward the circumference is a widening gyre from out of the depths of the centre to a shallowness or dispersal of being, or a “shadowiness” of being on the circumference. In this shallowness, the soul is more easily susceptible to the influences of evil and to being led by deception and machination. The soul is furthest away from self-knowledge when it is mired in the outer influences of the sphere.

In Preface II to this writing on “The Prince of the Two Faces”, we noted the statement of the French philosopher J. P. Sartre that “Hell is other people” and said that it illustrated the gap between love or eros and intelligence (nous, spirit, mind) as well as “thinking” or “thought” and how these are presented through the logos in the modern age when thinking and thought are understood as “information”. How love and intelligence (nous, spirit, mind) have come to be understood and how they relate to logos and eros is what must be undertaken at this time. Of course, these writings are simply impertinent precis of what are some of the most complex and troubling ideas present in our being-in-the-world today.

Plato’s discussion of the Divided Line occurs in Bk VI of his Republic. In Bk VI, the emphasis is on the relation between the just and the unjust life and the way-of-being that is “philosophy”. Philo-sophia is the love of the whole for it is the love of wisdom which is knowledge of the whole or the aspiration towards knowledge of the whole. The love of the whole and the attempt to gain knowledge of the whole is the call to ‘perfection’, ‘completeness’ that is given to human beings. Since we are part of the whole, we cannot have knowledge of the whole. This conundrum, however, should not deter us from seeking knowledge of the whole and, indeed, this seeking is urged upon us by our erotic nature. It is the urge to be god-like and can lead to tyranny. All human beings are capable of engaging in philosophy, but only a few are capable of becoming philosophers. As human beings, we are the ‘perfect imperfection’. We are ‘perfect’ in our incompleteness.

The whole is the Good (A-E); and that which is is part of the whole so it must, at some point, participate in the Good of which it is a part to some extent. That which we call the ‘good things’ of life such as health, wealth, good reputation, etc. are subject to change and corruption because they are not the Good itself. These are the things that we love. They are wholly in Time. To only love the ‘good things’ is to love the part, and this love of the part channels one off in another direction from that initial erotic urge directed toward the whole or the Good. This is why the ‘good things’ in themselves can become evils and why we can become obsessed with, and succumb to, the urges we feel for their possession. The desire for immortality and the desire for will to power can become hubristic. They can lead to tyranny.

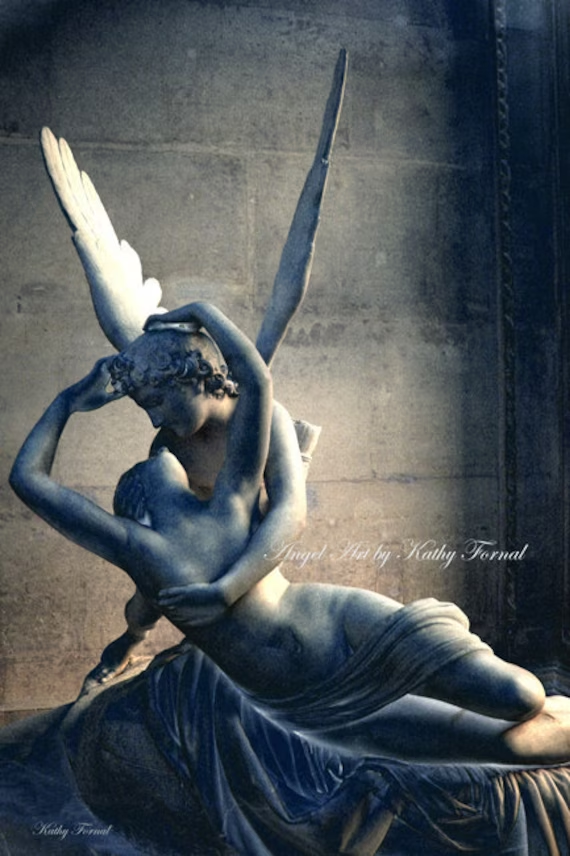

Eros is not the winged cherub or child named Cupid (which is derived from the Romans), nor is it merely the sexual urge which is the modern day focus, thanks primarily through the writings and works of Freud. “Love (eros) is the oldest of all the gods,” says an old Orphic fragment. Another Orphic fragment runs: “Firstly, ancient Khaos’s stern Ananke (Necessity, Inevitability) and Kronos (Chronos, Time) who bred within his boundless coils Aither (Aether, Light) and two-sexed, two-faced, glorious Eros (Phanes), ever born through Nyx’s (Night’s) fathering, whom later men call Phanes, for he was first manifested.” This Orphic fragment is saying the same as the Book of Genesis from the Hebrew Bible: “1 In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. 2 And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. 3 And God said, “Let there be light”: and there was light. 4 And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.” The “light” and Eros are born simultaneously, and this birth is the connection between the Good (God in the Hebrew Bible), the Logos (Intelligence, Mind, Spirit) and Love or Eros between the Intelligence and Love.

Eros is associated with Time; Logos is associated with Space. It is the Logos which grants and gives “form” and “shape” to the void that is prior to Being. Both Time and Space are associated with Ananke Necessity. Ananke is associated with Eros.

Acts of creation are ones that arise out of love, and sometimes that love can be misguided if it is not properly directed by the Logos. Love requires withdrawal and the allowance of things to be if it is to be true. It is an ‘owning’ that is a ‘disowning’ that allows care and concern to grow within its ‘space’, its site. Both Love and the logos allow themselves to be given shapes and forms that are necessarily further from the real truth of the things that are. These shapes Plato calls the shadows.

Plato’s Divided Line from Bk VI of his Republic is a visual representation of the journey of the individual soul that is outlined allegorically in Bk VII of the text in the allegory of the Cave. The Divided Line is the logos as a representation of enumeration or number, while the allegory of the Cave is the logos as mythos or “word” i.e. poetry, and in both cases we are meant to “behold” that which the logos reveals. Both the Divided Line and the Allegory of the Cave are abstractions. The Allegory is intended to be more ‘moving’ emotionally than the speeches outlining the Divided Line. In the Allegory, for instance, there is an emphasis on the physical pain that is involved in the turning toward the Good since we are beings in bodies. There is an emphasis on eros as pathos.

The Divided Line distinguishes between the two faces of the Logos and the two faces of Eros. This distinction is done with regard to how ‘reason’ or the logos (that part of the soul which is called the logistikon by Plato) is to be understood and, subsequently, how eros is to be understood in the concrete details of human living. These details are made even more explicit in the speeches related in the Platonic text Symposium. From these concrete details we can understand the gap that exists between Intelligence and Love in our modern understanding. One face of the Logos is language as rhetoric which is the language that informs the many. Artificial intelligence and its “reason” is rooted in “rhetoric”. The other face of the logos is rooted in dialectic: the “informing” that occurs between two or three individuals that assists the soul on its way to self-knowledge.

For Plato, Eros as Love is what distinguishes the higher Eros from the lower eros. While the higher Eros emphasizes withdrawal and “letting be”, the lower eros is a possessing, holding and consumption of that which is “loved”. The higher Eros emphasizes an engagement in but not a possession of that which is loved. In some of the myths regarding Eros, Psyche the human soul, first hopes to catch a glimpse of Eros and then to hold and possess him. When she does so, Eros disappears and she must begin a long and painful journey to find him again.

Love has no place in the political; it is anti-political in that it is primarily a private act and the political deals with public acts which are associated with the thymoeidic part of the soul and the community at large. The thymoeidic part of the soul is torn between the public and the private spheres. The political emerges out of the private individual things, just as the city emerges from out of the household, the community from out of the family, the family from the individual body.

The root of the agon or conflict between philosophy and the political, as it is for philosophy and poetry, is how Love or eros is understood and interpreted. Alcibiades, the ‘political beast’ who shows up uninvited in the Symposium, has a passion for Socrates, but this passion is not Love. Socrates knows who Alcibiades is and what his nature is so he spurns Alcibiades’ advances and yet at the same time tries to lead him to philosophy because Socrates is aware of Alcibiades’ exceptional nature. Socrates recognizes the greatness of Alcibiades’ ‘spiritedness’ (thymoeides) and tries to lead him to philosophy but fails to do so. Alcibiades’ failure is the result of his love for the polis and for the favours he receives from the many. That many historians attribute the fall of Athens to the Spartans to Alcibiades’ betrayal of the Athenians illustrates to us the importance of this event in the lives of the participants in both Republic and the Symposium and to the history of the West in general. It signified nothing less than the end of what we call the Golden Age of Greek civilization and culminates in the imperialism of Alexander the Great.

Thinking, thought and self-knowledge are co-related. The openness to love and intelligence are co-related. Where true thought is not present, there is no self-knowledge, there is no “intelligence”. Where there is no self-knowledge, there is no sense of ‘reality’. Where there is no sense of reality, there is no knowledge or recognition of good and evil. Where there is no knowledge or recognition of good and evil, there is no possibility of “human excellence” or arete. Without a sense of “human excellence”, there is no polemos or strife within the individual soul to resist the temptations to succumb to evil actions through the many urges of the lower eros and one is unable to move to a higher state of consciousness nor, in many cases, does one desire to move to a higher state of consciousness. One finds the pleasures of the lower eros enough. This satisfaction was found among the Epicurean philosophers and the later Empirical philosophers.

In its urging towards an ascent, Eros’ affect is to make us love the light and truth and hate darkness and falsehood. Care and concern for others and our sense of “otherness” develops from this higher Eros’ erotic urge. The ascent from the individual ego and its love of the part, experienced in the love of a single, beautiful other, to a knowledge of the whole and the love of the whole of things is a process that the immortal part of the soul (logistikon) undergoes in its journey towards “purification” from the love of the meeting of our own necessities and urges (epithymetikon) to the love of the Good. “Depth” arises from the ascent which is toward the centre of the sphere. The descent brings about our desires for the surfaces of things, which is the lower form of eros. These are located on the outer circumference of the sphere. Evil is a “surface phenomenon” and eros is a part of it, and evil is located and thrives on the outer circumference of the sphere. It is the given of the human condition, of its being-in-the-world.

The content which is given to us in the image of the Divided Line in Bk VI of Republic is emphatically ethical for it deals with deeds, not with words. The philosophic way-of-being is erotic by nature. To be erotic is to be in ‘need’; sexuality is but one powerful manifestation of the erotic in our lives and it illuminates our desire for immortality through the procreation of children. The procreation of children is the recognition of the ‘otherness’ that is our being- in- the- world. In general, the two faces of Eros have to do with mortality and immortality. They are bound together like two sides of the same coin. It is the awareness of our mortality that makes the desire for otherness a need.

The ‘spirited’ (thymoeides) part of the soul acts as a mediator or metaxu between the logistikon or “rational” part and the epithymetikon or “appetitive” part of our souls which in turn determine our various “militaristic” and sexual passions which manifest themselves in our love of sports and competition or our love of wealth among many other varied activities and pursuits in the various worlds that we participate in. This is eros as pathos in our human natures.

When such drives dominate the soul, there is a predilection for politics, for power within the community or polis to make such an acquisition of such goods or objects easier. Such a desire for power is rooted in a desire for immortality through ‘honour’ and ‘fame’ through the thymoeides part of the soul. The ‘procreation’ that is the root of sexuality is the desire for immortality through offspring. This desire for immortality through offspring is the desire for the Incarnation, the ‘procreation’ of the Good, the begetting of the Good in beauty. The separation of the desire for offspring from the orgasm that is the result of that sexuality is but one manifestation of that gap between intelligence (nous, mind, spirit) and love that is revealed in Sartre’s “hell is other people” statement noted above. It is a manifestation of the tyrannous soul.

The philosophic soul reaches out for knowledge of the whole and for knowledge of everything divine and human. It is in need of knowledge of these things, to experience and to be acquainted with these things. This noetic knowledge is a gnosis, an en-owning of the knowledge of which one has taken “possession”, not through consumption but through participation. It is an active being-in and concern-with and yet, at the same time, a “letting be” through a contemplative consideration of what is close at hand. The non-philosophic human beings are those who are erotic for the part and not the whole. They are deprived of knowledge of what each thing is because they see by the borrowed light of the moon (the images of the imagination that are our representations) and not the sun; their light is a reflected and dim light. They wish to control, commandeer and consume that which has emerged into being. The hubris of human beings, and their great danger both to themselves and to otherness, is to try to commandeer and control being itself.

Eros is the “sun-like” quality of the “eye” that allows the eye to perceive the Sun’s goodness. Eros acts as the metaxu or the “between” or the “in between”, the mean proportional of geometry, the “open” space that occasions or establishes a relation between two incommensurate properties or things. In the prison cells that are our ’embodied souls’, the ‘form’ that the logos takes acts as a barrier but it is also a way through. The metaxu are ‘means’, what we call the ‘goods’ of the world. As such, they are the ‘bridges’ to the Good itself.

Metaxu can also be translated as “among,” “in the midst of,” or “in the meantime”, the “in-between” space or that “open” region that is the realm of mediation between two distinct realities or concepts such as is shown to us in each segment of the Divided Line. “Metaxu” can be seen as a space of mediation between the divine and the human, or between the earthly and the spiritual. It is a bridge. It is Eros as the “space” or “site” of the longing and striving for the something that is beyond the immediate. It is the meeting point or place of Eros (Time) and Logos (Space) and from within it, truth as aletheia or ‘unconcealment’ occurs in the revelation of the beauty of the thing being observed which is further extended to the beauty of the world or the whole. The beauty of the world is the parousia or “presence” of the Good yet, at the same time, the metaxu form the region of good and evil. They act as barriers to the Good.

In the Allegory of the Cave the prisoners see the shadows of the artifacts carried before the fire that the artisans and technicians have ignited and tend. They have no clear pattern or ordering in their souls, and they lack the experience (phronesis or wise judgement) that is tempered with sophrosyne (moderation) that they have acquired through the experience of suffering or strife. The purpose of suffering is self-knowledge which is revealed, ironically, as the destruction of the “ego” or self. The best example of this that we have in English literature is Shakespeare’s King Lear. In the play, King Lear has become an “0”, a ‘nothing’, and the destruction of his pride and his loss of place in society allows him to gain a new sense of otherness and to be reborn. In his rebirth, the first thing that he apprehends is Cordelia, the living embodiment of truth and truth-telling in the play. From the play, it is clear that the process of re-birth is not an easy one.

The philosophic soul is one that has an understanding endowed with “magnificence” (or “that which is fitting for a great man” and is thus distinguished from the understandings of those who are not “great men”) and is able “to contemplate all time and being” (486a) i.e. the understanding that is in the soul of the philosopher is ‘prophetic’. The prophet speaks ‘the highest’ speech. The philosophic soul has from youth been both “just and tame” and is not “savage and incapable of friendship”. The philosophic soul is not ‘rough’, but ‘smooth’. The meaning of the statement above Plato’s academy is not that “No one enters unless he knows geometry” as a specific study of the mathematical arts, but that “No one enters unless he has the capability of being a friend”. (See the connection to The Chariot card of the Tarot where the two sphinxes, one white and one black representing the mystery of the soul, are in contention or strife polemos with each other.)

In looking for the philosophic way-of-being-in-the-world, Socrates concludes: “….let us seek for an understanding endowed by nature with measure and charm, one whose nature grows by itself in such a way that as to make it easily led to the idea of each thing that is.” (486d) The philosophical soul is as it is by nature. It grows by itself from out of itself. It is not a product of education alone, although education can assist it on its way in the same way a farmer attending his crops assists his crops on their way. Socrates sees his main task as being a mid-wife.

Is this all souls or only some souls? Are all souls capable of attaining the philosophical way of being? The modern answer to these questions, through the impact of Christianity and the modern philosophers, is a “yes” while the ancient answer appears to be a “no”. Saints and philosophers are rare plants to the ancients.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet may be said to be a play regarding this conflict in the thymoeidic part of the soul. Hamlet’s ‘doubt’, his need for certainty and surety, prevents him from seeing the reality in which he has been placed and from taking the proper action necessary which is the fate that has been given to him. Hamlet’s doubt gives him an ‘unbalanced soul’. In contrast, Horatio is shown by Hamlet to be an example of the ‘balanced soul’ who is in possession of what Aristotle called phronesis:

“…for thou hast been

As one, in suffering all, that suffers nothing,

A man that fortune’s buffets and rewards

Hast ta’en with equal thanks: and blest are those

Whose blood and judgment are so well commingled,

That they are not a pipe for fortune’s finger

To sound what stop she please.” (Hamlet Act III sc. ii)

Horatio is an example of a ‘just man’, for his “balanced soul” allows him to take actions that are well-considered, wise. He is able to take life’s goods and evils with equal thanks, and this dispassionateness allows him to make the proper judgements at the appropriate time. This ability to make proper judgements is the proper relation of the logistikon and thymoeidic parts of the soul. The epithymetikon part of the soul creates distortion and chaos for the judgement when it dominates. The flute or pipe, the wind instrument, is the musical instrument of Dionysus, the god of tragedy, while the lyre or stringed instrument is the instrument of the god Apollo. Apollo is the god associated with the Sun and with truth.

Socrates uses an eikon or image (A-B of the Divided Line) to indicate the political situation prevalent in most cities or communities. The eikon uses the metaphor of the “ship of state” and the “helmsman” who will steer and direct that ship of state. The rioting sailors on the ship praise and call “skilled” the sailor or pilot, the “knower of the ship’s business”, the man who is cleverest at figuring out how they will get the power to rule either by persuading or forcing the ship-owner to let them rule. Anyone who is not of this sort and does not have these desires they blame as “useless”. They are driven by their “appetites”, their hunger for the particulars which they perceive as ends i.e. what Plato describes as human beings when living in a democracy, oligarchy, or a tyranny. In the modern age, we have killed off the ship-owner and replaced him with the ‘helmsman’, the cybernaut.

This is the reason why Plato places democracy just above tyranny in his ranking of regimes from best to worst, tyranny being the worst since both these regimes, democracy and tyranny, are ruled by the appetites and not by phronesis and sophrosyne or what we understand as ‘virtue’. (Democracy’s predilection for capitalism is a predicate of the rule by the appetites and the lower form of eros. The soul’s power to distinguish between self-interest and the common good becomes weakened or corroded under democracy so that tyranny is the ultimate result. It is the destruction of the sense of otherness in the soul. Human beings are, as individuals, tyrannic by nature and this is primarily due to the influence of eros. Technology has a great impact in increasing this tendency toward tyranny and towards the tyrannic soul. We seek the ‘gigantic’ and ‘intense’ rather than the ‘pure’.)

The erotic nature of the philosophic soul “does not lose the keenness of its passionate love nor cease from it before it has grasped the nature itself of each thing which is with the part of the soul fit to grasp a thing of that sort, and it is the part akin to it (the soul) that is fit. And once near it and coupled with what really is, having begotten intelligence and truth, it knows and lives truly, is nourished and so ceases from its labour pains, but not before.” (490b) The language and imagery used here is that of love, procreation, and childbirth, and this indicates its connection to both the lower and higher forms of Eros.

The world of the sensible must be experienced through the body, the epithymetikon part of the soul. With regard to the Divided Line, the world of the sensible, the Visible, “is equal to” the world of Thought: the mathemata or “that which can be learned and that which can be taught”. That which can be learned and that which can be taught is initially the visible, that which can be sensed and experienced. Socrates sees himself as a mid-wife, helping to aid this birthing process that is learning. It is a birthing process because it is a poiesis or a “bringing forth”.

At Republic Bk. VI 508 b-c, Plato makes an analogy between the role of the sun, whose light gives us our vision, to the visible things to be seen and the role of the Good in that seeing. The sun rules over our vision and the things to be seen. The eye of seeing must have an element in it which is “sun-like” in order that the seeing and the light of the sun be commensurate with each other. Vision does not see itself, just as hearing does not hear itself. No sensing, no desiring, no willing, no loving, no fearing, no reasoning can ever make itself its own object. Eros as pathos cannot be grasped through human reason but can only be spoken of through human language.

The Good to which the light of the sun is analogous, rules over our knowledge and the real being of the objects of our knowledge (the forms/eide) which are the offspring of the ideas or that which brings the visible things to appearance and, thus, to presence or being, and also over the things that the light of the sun gives to vision: “This, then, you must understand that I meant by the offspring of the good that which the good begot to stand in a proportion with itself: as the good is to the intelligible region with respect to intelligence (D-E) and to that which is intellected (C-D), so the sun (light) in the visible world to vision (B-C) and to what is seen (A-B).” This “begetting” of the Good hints at its connection to Eros and to Logos.

Details of the Divided Line: Section A-B

Eros and Logos manifest themselves in the A-B section of the Divided Line as the mediation points or metaxu that unite the tripartite soul of the human being to the things that are. “A” of the Divided Line is Eikasia or Imagination. These are the likenesses, images, shadows, models, imitations, and icons that our vision produces. They are the “schema” and “plans” that human beings put forward in order to create their understanding of their worlds. “To produce” is to “pro-create”, to “bring forth”. The end of all procreation is the desire for immortality. Nature’s procreation is sempiternal: it exists eternally within Time. For Plato, Time is the moving image of eternity. Our desire for children is the desire for immortality on the natural level. Eternity is that which exists outside of Time. Eros functions as that desire for immortality through procreation manifested in sexuality on the physical level. When the desire for children is divorced from sexuality, this is but one example of where human beings enter that stage where their sense of “otherness” is gradually eroded and their desires become “tyrannous”, self-serving. For human beings, children are the fact of “otherness”. In literature, for example, the tyrant Macbeth and his wife have no children.

Section A-B of the Divided Line is what we understand as ‘civilization’, those artefacts created by human beings that are distinct from nature because they are made by human beings. They are the shadows on the walls of the Cave. Nature and convention are in opposition to one another, and it is by nature that we are measured even though we believe that it is we who do the measuring. This is why eikasia or imagination is placed below Nature on the Divided Line; Nature is of the higher order or a higher dignity when it comes to Truth and its unconcealment.

In the illustration shown, the two diagonals that emerge from C and culminate on the surface of the sphere at B are two types of thinking associated with techne that occur in the C section of the Divided Line: poetic thinking or the thinking of the arts, and the thinking that is the know-how of the artisans and technicians. In both types of thinking, there is a metaxu that is needed, a ‘light’ that is required, and that ‘light’ is studied through geometry and the dialectical discussions that surround geometry. “Depth” occurs by a movement towards the centre of the sphere, not from the “height” that is the sphere’s surface. This movement is provided by eros. Goodness is at the sphere’s centre; evil is on the surface.

In the cosmology of the poet and and painter William Blake, the scientist Newton is depicted at the bottom of the sea sitting upon a rock (which oddly looks like a urinal or toilet) creating a geometric cone upon a scroll. He is surrounded by darkness. There is a polypus or octopus swimming by, and this creature is equivalent to the Great Beast of Plato i.e. the political, or the social. The fact that Newton is not putting his geometry down in a book or in stone but on a scroll indicates that Newton is using the creative imagination. As a scientist, or rather the scientist for Blake, Newton is joined with Bacon and Locke who, as seekers of truth and despite their errors, appear in the heavens on the day of the Apocalypse among the chariots of the Almighty, counterbalancing Milton, Shakespeare, and Chaucer, the greatest representatives of the the Arts. Theses philosophers and poets are all English-speaking.

Plato has a similar line up in his Symposium with the greatest representatives of the arts and scientists present at the banquet in which the topic of Eros will be discussed. The subject of both the Arts and the Sciences is the beautiful: order, proportion, harmony. The Sciences deal with these in the realm of the suprasensible and the necessary while the Arts are concerned with the sensible and contingent. Chance and evil, necessity, are present in both.

The essential urge of Eros is the desire for immortality and this is shown in Eros’ affect on all three parts of the Platonic soul. The epithymetikon (appetite or desire, which houses the desire for physical pleasures, especially sexuality) partially realizes this desire through the begetting of offspring. This ‘begetting’ mirrors the begetting of the eidos through the ideas: the offspring, while appearing to be the same are different . In all cases, the ‘image’ of Beauty in the outward appearances of the mortal things is what attracts and urges us to ‘possess’ and ‘consume’ those things which we desire. Our belief is that in possessing and consuming such things, immortality will follow. It is Khronos (Time) who eats his own children.

The image of a thing of which the image is an image are the things belonging to eikasia or the “imagination”. This is what we understand as ‘civilization’. These are the things ‘procreated’ by human beings through the logos whether the logos be understood as representational thinking such as mathematics or logic, or the creative works of the technites or artists and technicians, such as writings or shoes. The idea that is to be the next pair of Nikes was always already there. It was waiting for the artisan and technician to give birth to it, to “pro-create” it, and bring it forward into being. This is the distinction between the procreation of Nature and that of human beings: nature’s procreation is in itself from out of itself, while human beings are a combination of this (sexuality, nature) and “in another for another” (techne) i.e. the next pair of shoes derives from materials that are not of human beings nor of human making.

We are ‘reminded’ of the original by the image: the Beauty of Nature is the “image” that reminds us of the Good. Just as Nature is sempiternal, eternally in Time, the Good is eternal, eternally outside of Time. Nature is a mirror-image of the Good while Nature is, at the same time, dominated by Necessity Ananke. Necessity is Time. And there is a great gap separating the Necessary from the Good; that gap is the whole of Time and Space. That gap is mirrored in the separation of Love from the Intelligence in the A-C section of the Divided Line. The mediation of what we call “Intelligence” (mathematical calculation, the principle of reason) is a mirrored image of the mediation of Love and the things that are. The Intelligence that is the principle of reason is a “possessing”, commandeering logos, while the Intelligence that is Love is a ‘letting be’ and a contemplation of the things that are. In our being-in-the-world, we wish to consume the objects of our senses. The beautiful is that which we desire without wishing to eat it. We desire that it simply should be. To do so requires the renunciation of the imagination and the products of the imagination. This is not an easy thing to accomplish.

The sphere of Space encloses the beings that are in Time. It is the logos that encloses beings within Time. It is the Logos that establishes limits and brings the things that are to a ‘stand’. The soul, psyche, of human beings is eternally in Time. When the soul is assimilated into the One that is the Good, it ceases to be in time. Nature is eternally in time. Time is the moving image of eternity. Eros is a moving image of the Good that is beyond time. Nature is sempiternal, everlasting, endless.

The thymoeides part of the soul (spiritedness, which houses anger, as well as other spirited emotions), realizes the desire for immortality in its desire for “eternal fame and glory”. There is a “beauty” (kalon) in the carrying out of great deeds. We cannot, for example, deny that there is no beauty in the site of the Three Gorges Dam. Public care and concern (“spiritedness”) is linked to self-interest and it is here that we find the motivation of the politicians. The desire for immortality is in the desire for the doing of great deeds which will bring the individual before the public in some manner. Whether through military campaigns, the creation of ‘works’, or sporting achievements, this recognition is another way in which the soul tries to achieve a partial immortality, eternal fame, just as children are a ‘partial immortality’ in the physical realm.

The techne or artisan is the servant of the people: “in another, for another”. His “work” illustrates his mastery of a ‘part’ of knowledge, his own art, his “know how”, that knowledge that the philosopher aspires to for the whole of things. This mastery is driven by the thymoeides part of the soul, that which is driven for the mastery (thymus) of the eidos (the outward appearances of things).

The logistikon is that part of the soul that is the smallest part of the soul, and it is the only part of the soul that is beyond Necessity because it is part of the Good itself. In the illustration provided below, the logistikon is the centre point of the sphere that may be said to be within Time and out of Time, or it is at least the closest one can come to in being out of Time. References to the logistikon are found throughout our literature in myth and fairy tales as the ‘smallest’ of things that grow that have the greatest consequence. The sphere itself is as a great Wheel of Fortune that is in motion. This is Necessity. The only way of escaping the turnings of the Wheel is by being at the centre of it (King Lear Act V sc. iii).

In the A-B section of the Divided Line, the logistikon acts as that which ‘ties things down’, the logos that gathers things together and holds them in place. The ‘knowing’ and ‘making’ of the artisan and the technician (technology) is the interaction between the logistikon and the thymoeides parts of the soul of the artisan and technician. It is the face of the logos that is the principle of reason, of logic, and the language that forms our collective discourse (rhetoric). One of the faces of the Logos is that it is the “form” that makes the “informing” possible.

Section B-C of the Divided Line: Technology as Shadow

Section B-C of the Divided Line corresponds to physical things and to that which can be ‘counted on’ i.e. it represents trust, confidence, belief, faith (pistis). The physical things are those that can be seen or perceived with the senses. It is eros as ‘light’ that provides this capability. They are the things that are at our disposal, the ready-to-hand. In the Divided Line B = C: the physical things and our trust/belief in them is equal to the thoughts that we can think of those things through the representations of our perceptions of those things with our senses i.e. the Forms or Eidos of the things, the “outward appearances of the things”.

We have two definitions of what human beings are that have come down to us historically from the Greeks and the Latins. From the Greeks, human beings are the zoon logon echon, “the living being that dwells and perdures in language”. From the Latins, humans are the animale rationale, the “rational animal”. From the Latin definition arises the principle of reason, and this is what is in operation in section C of the Divided Line and determines one type of thinking and the logos from which it is derived.

A principle contains within itself a ratio, a reason for something else. The principle of reason is the ground/reason for all other principles and that means for what a principle is per se, for what a statement is, for what an utterance is. That about which the principle of reason speaks is the ground of the essence of language, of logos. This ground or essence is what we understand as one of the faces of Eros. Principles are derived from axioms. In Greek, axiom means “to find something worthy”. “Worthiness” is the trust, belief given to us by the “self-shining forth” of the axioms. Given our illustration, the problem is that the principle’s ratio is itself an ‘irrational number’, a contradiction.

The axioms determine the principles that have been derived from them. In Greek axiom is “to let something repose in its countenance and preserve it therein”. It is related to representational thinking and to eidos. Principia

are the sort of things that occupy the first place, that stand first in line.

Principia refers to a ranking and an ordering. They are our objects of sophia.

The ordering realm (Section A-C) is the realm of principles (sophia). We have determined that the sole purpose of axioms is to secure a system that is free of contradictions. The axiomatic character of axioms is to eliminate contradictions. Our concepts, axioms, principles (fundamental principles) serve the axiomatic securing of calculative thinking. What we call science is axiomatic, but for Plato science does not think in the manner that philosophers think.

For the philosopher Leibniz, the principle of reason is the principle of rendering sufficient reasons. To render in Latin is “to give back”. Our “cognition” (ways of knowing), “consciousness” is the rendering back of reasons. In Latin, cognition is representatio: the object, what is encountered, is presented to the cognizing “I”, presented back to and over against it, and thus made present. “Ob-ject” comes from ob-“against” and jacio “that which is thrown”.

Cognition must render to cognition the reason for what is encountered—and that means to give it back to cognition if it is to be a discerning cognition. “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” because a sufficient reason, a ratio, cannot be given in an account of what is considered to be “beautiful”, although we have the theory of aesthetics which attempts to do so and which itself is based on the principle of reason. Under the principle of reason, eros becomes stifled, exsanguinated.

The principle of reason is reached only when it is understood as the fundamental principle of demonstrations: i.e. the fundamental principle of statements such as those given in our research, experiments, essays, presentations, etc. It is the principle of reason which is the dominant form of the logos in section C of the Divided Line in our modern age. The principle of reason is a Principle for sentences and statements i.e. for what is called “philosophical” and scientific knowledge (methodologies). The principle of reason is necessary for the rendering of reasons in the true statement/sentence. The principle of reason is the fundamental principle of the necessary founding of sentences and principles. This is what makes the principle of reason the essence of what we call Artificial Intelligence and the meta-languages associated with it.

What is empowering about the Principle is that it pervades, guides and supports all cognition (ways of knowing) that express themselves in sentences and propositions. The principle of reason is valid for everything which in any manner is. Cognition, our “ways of knowing “, is a kind of representational thinking. In this “presentation” something we encounter comes to a stand, is brought to a standstill as object. For all modern thinking the manner in which the things “are” is based on the objectness of objects. For representational thinking, the representedness of objects belongs to the objectness of objects. This is what Plato understood as “the shadows” and this is represented by the square in the illustration provided above.

“Ob-ject” comes from the Latin which means “the thrown against”. The “against” of the object must be a founded one: how the object is. Something

is, which means that it can be identified as being a being, only if it satisfies the fundamental principle of reason as the fundamental principle of founding. The principle of reason is the fundamental principle of cognition (ways of knowing) as the Principle for everything that is. It establishes our “under-standing” of what and how things are in the world that is ready-to-hand. It is the reason why “beauty must be in the eye of the beholder”.

We are who we are as human beings only insofar as the rendering of reasons empowers us. This is what makes us the animale rationale. It is from this “empowerment” that we judge what is human and what is not, what is sane and what is not, what is just and what is not, etc. This empowerment, the demand to render reasons, threatens everything of humans’ being-at-home and robs us of the roots of our subsistence i.e. of everything that has made human beings great up till now . It is the nihilism that threatens civilization, the ceasing of concern for what “human excellence” is, for what “virtue” is. There is a connection between the demand to render reasons and the withdrawal of roots, and the subsequent rootlessness of modern humanity.

For the Greeks, ousia or presence was understood as the thing’s way-of-being in the world. The city or society came about because of the body and the needs of the body. The city is a product of the procreation of eros writ large. The city was, thus, the individual writ large. The city represented the individuals which composed it in that its regime would reflect the opinions of those who are predominant in the community, those who hold power. It is because of this power that Plato considers it the Great Beast.

B-C in the Divided Line is the point where we see the two faces of Eros as well as the two faces of the Logos. The wants and the needs of the body for the individual are radically private and at the same time require other human beings for their fulfillment. The city or polis is an artefact brought forth by human beings and it has both the characteristics of being a natural thing and those of an artificial thing. Plato’s Cave in his Allegory is both a natural thing and a product of human invention and production. As the law of necessity controls the realm of nature, so too do laws control the ‘life’ that is shown in the polis. The walls of the Cave reflect the projected shadows of the interpretations of the Cave given through the representational thinking that is the Eikasia or “imagination” of the cave-dwellers. It is here that the essence of technology as “information” or the “form that informs” finds its source.

In the image of the Divided Line, the first thing the dweller inside of the Cave sees are the reflections of the shadows upon the walls of the Cave. These shadows or images form our views of the things that are. These provide us with our “understanding” of things whether they are the things of nature, the artefacts which human beings produce, or the things that are the products of our representations of them such as our sciences or our arts. Our “understanding” is an interpretation of the things, not an under-standing of the things themselves. Eros is not satisfied with these understandings and longs for the things in themselves. This is due primarily to Eros’ chief desire which is the achievement of immortality, that which is beyond change; and the things and our interpretations of them are subject to change.

In the B-C section of the Divided Line, the mind or logistikon part of the soul (the intelligence which became translated as ‘reason’ and so its connection to logos) is aided by the thymoeides or ‘spirited’ part of soul to attain to that object to which the appetitive part of the soul is directed. The appetitive part of the soul is urged by the thing’s “goodness” or perceived goodness, be it in food, drink, sex or whatever, and that this goodness will assist the body to survive and promote the soul’s search for immortality. The soul as a ‘one’, a whole, is directed or attracted by the kalon or beauty of the thing, to possess or ‘consume’ that which it perceives as beautiful. That which is perceived as beautiful is that which is ‘perfect’ or complete. Sexually, this is the individual beautiful human being at the beginning stages of the journey that leads to the perfection that is the Good (or immortality). The individual desires to “consume” the other human being so that the two may become one in a literal sense.

The word beautiful (kalos) is distinct from good (agathon) and it also means ‘fair’, ‘fine’, ‘noble’. Everything outstanding in body, mind or action can be so designated, and the aspiration for these qualities can be related to the thymoeides part of the soul and the eros which drives it. We have designated this quality as “human excellence” among human beings, arete, what we call “virtue”. What is loveable either to sight or mind is beautiful. It is what we designate as “moral” with the distinction that it is beyond obligation or duty, what we cannot expect everyone to perform. It is of a higher rank than the just, which every human being can be expected to perform. The core of a just political order was defined by “virtue” for the ancients, while today “freedom” is believed to be at the core of the just political society. Both of these views may be said to be present in A-C section of the Divided Line. This emphasis was directed by the eros that is the thymoeides part of the soul.

In earlier writings on this blog, it was recognized that the evil or wicked were not alone the individual criminals but those who wished to rule for their own self-assertion. Such people were more destructive of justice than those who ruled simply in terms of the property interests of one class. Because tyrants were the most dangerous for any society, the chief political purpose anywhere was to see that those who ruled had at least some sense of justice which mitigated self-assertion. This was at the core of earlier education systems. The IB, too, has this mitigation of self-assertion at its core. The great danger of the thymoeides part of the soul was its tendency to tyranny. This tendency is also part of Eros.

In Section A-B of the Divided Line, the logos of the logistikon of the soul is concerned with the calculation from which knowledge is derived. This calculus has shaped what we understand by modern science and is at the heart of what we understand as technology. It finds its place or site in that field of mathematics that we call algebra. Money, technology, algebra are analogous as signs of our worship of power.

As Eros is two-faced so, too, is the logos in the realms of the physical and imaginative. The “mathematics” (“that which can be learned and that which can be taught”) of the logos is of two types: the arithmos of the particular things, those things that exist in Time, those things that can be counted and counted on, and the geometria of that which exists in Space, those things that are the works of the Logos. As logos understood as the “calculable” through algebra comes to predominate so, too, does the notion of justice as “calculable” come to predominate (this is the modern view of justice i.e. “the greatest good for the greatest number”).

The thymoeides part of the soul is concerned with “passion”, and it is this passion which unites with the logistikon part of the soul and brings about the urge to attempt to attain immortality through ‘noble’ and ‘fine’ deeds or works. The understanding of what ‘fine’ deeds are is part of the ‘cognition’ or perception of how ‘human excellence’ is understood beforehand. We ‘love’ the beauty of ‘human excellence’ when it is shown to us. It is the passion to possess this beauty that compels us to perform excellent deeds in whatever context those deeds may be performed.

Section C-D of the Divided Line

Many will find the proposition that science does not think the most controversial put forward in this writing. What does it mean for Plato (and Heidegger) to say this? How does this statement cast a light on what we understand as artificial intelligence and on rationality in general?

The Forms or eide (the outward appearance of things) are begotten from the ideai which, in themselves, are begotten from the Good. “Begottenness” is of Eros. The forms give presence to things (ousia) through their outward appearance. The “seeing” of this presence is dependent on “sight” which, in turn, is dependent on the light of the sun. In order for this to occur, the eye must have something “sun-like” in it just as the soul must have something like “the good” in it to be able to “bring forth” the representations of the things that are in the mind or intellect.

There is nothing without thought; there is no thought without things. In the Divided Line, B = C. “Otherness” is a condition of being. Human beings are essential for being to be. Being needs human beings to be. Being is reality. What we call science is the theory of the real, the “seeing” of the real. (“And would you also be willing,” I said, “to say that with respect to the truth, or lack of it, as the opinable is distinguished from the knowable, so the likeness is distinguished from that of which it is the likeness?”) The “images” and “shapes” of things, the eide, such as the city or society is the individual writ large. The polis or city is a city of artisans and technicians, of technites. The “knowing one’s way about or within something” begins in the household and caters to the production of novelty, efficiency. The logos, like Eros itself, is two-faced or of two types. The jumping off point or the leap is the recognition that the Sun in the realm of Becoming (Time), like the idea of the Good in the realm of Being, is responsible for everything that is. The Sun is Time as the moving image of eternity, and all that is in being owes its existence to Time. The Good is eternity, and all that is in Being and Becoming owes its existence to the Idea of the Good.

Dianoia is that thought that unifies into a “one” and determines a thing’s essence. The eidos of a tree, the outward appearance of a tree, is the “treeness”, its essence, the idea in which it participates. We are able to apprehend this outward appearance of the physical thing through the forms or eide in which they participate for these give them their shape. The understanding, the hypo-thesis (dianoia) is the “standing under” of that seeing that is thrown forward, the under-standing, the ground. Thought under-stands the limits and boundaries of things and gives them “measure” through the use of number or language logoi. The giving of measure to the seeing is geometry and geometry deals with ratios; and from it, the hearing of the harmonia of music, the music of the spheres, is recognized and produced. The music of the spheres is the recognition of the whole of which each being is a part, and how that part is related to the whole. Thought comprehends the “measure” of the things that bring about “harmony” and unites the individual being or thing to the whole. The proportionals are arranged about a “mean” which is “hidden” or “irrational”. The principle of stringed instruments and their ratios is applicable to the whole of the universe, both the visible and invisible.

Section D of the Divided Line is the Ideas Ideai which are begotten from the Good and are the source (archai) of the Good’s presence parousia amidst that which is not the Good, both in being and becoming. The Good is seen as “the father” whose seeds (ideai) are given to the receptacle or womb of the mother (Space) to bring about the offspring that is the world of A-E (Time), within the whole of things within Space. The realm of A-E is the realm of the Necessary. (Timaeus 50- 52e). The dialogue of Timaeus occurs the morning after the dialogue that we call Republic. It is the continuation of an ascent from the eikasia of the imagination and opinion of Section A (Republic) to the physical reality of Section B of the Divided Line (Timaeus). Timaeus is a revealing of the Ananke, what the Greeks understood as Necessity. The dialogues of the Sophist, Theatetus and The Statesman illuminate Section C of the Divided Line. Symposium and Phaedrus are dialogues that help to illuminate Section D.

Because the ideas are begotten from the Good, the ideas are the essences of things, their “oneness”, that which they really are. The ideas in turn beget the eidos which bring things to presence in their ready-to-handedness in time for human beings. The things come to a stand through the eidos and give us what we call our “understanding”. The nature of this understanding is pre-determined by the logos within being, by the “frame” or the “form” that is a product of the logos.

Noesis is often translated by “Mind” but “Spirit” might be a better translation. Contemplation, attention, “dialectic” are the activities of noesis. Knowledge (gnosis), intellection, the objects of reason (logoi but not understood as logistics but as noesis, ideai, episteme) is what is understood as “knowledge” in this section of the Divided Line. “Knowledge” is permanent and not subject to change as is “opinion”, whether “true” or “false” opinion. Opinions develop from the pre-determined seeing which is the understanding of the essences of things prevalent at a certain time. Understanding is prior to the interpretation of things and the giving of names to things.

The Idea of the Good (agathon) is what provides “the truth to the things known (i.e. their “unveiling”, their “showing forth”) and gives “the power to the one who knows… and, as the cause of knowledge and truth, you can understand it to be a thing known; but, as fair as the two are – knowledge and truth – if you believe that it is something different from them and still fairer than they, your belief will be right.” (Republic 508e – 509a) The Idea of the Good is the essence of things that come to be whether in the Visible or the Invisible realms. The Good is beyond both Time and Being. When the soul is in direct contact with the Good, gnosis is achieved and the soul is no longer in Time for it becomes part of the One of all that is. The Good is responsible for (aitia ‘the cause of’) the knowledge and truth (aletheia, unconcealment) of all that is. Without it, knowledge and truth could not be attained. Everything would be ‘irrational’. Eros as Love and the Beautiful is this face of the two-faced Eros.

The whole of the Divided Line (A-E) is the Good’s embrasure of both Being and Becoming, that which is both within Time and Space. This embrasure is spherical in shape. The Good itself is beyond this sphere that is Being and Becoming (i.e. space and time) and there is an abyss separating the Necessary (which is both Space and Time) from the Good. Within the Divided Line, that which is “intellected” (C-D) is equal to (or the Same i.e. a One) as that which is illuminated by the light of the sun in the world of vision. (B-C)

Details of the Divided Line

Below is a summary of the points made regarding the Divided Line:

“This, then, you must understand that I meant by the offspring of the good that which the good begot to stand in a proportion with itself: as the good is in the intelligible region with respect to intelligence (DE) and to that which is intellected [CD], so the sun is (light) in the visible world to vision [BC] and what is seen [AB].”

| E. The Idea of the Good: Agathon, Gnosis “…what provides the truth to the things known and gives the power to the one who knows, is the idea of the good. And, as the cause of the knowledge and truth, you can understand it to be a thing known; but, as fair as these two are—knowledge and truth—if you believe that it is something different from them and still fairer than they, your belief will be right.” (508e – 509a) | |

| D. Ideas: Begotten from the Good and are the source of the Good’s presence (parousia) in that which is not the Good. The Good is seen as “the father” whose seeds (ἰδέαι) are given to the receptacle or womb of the mother (space) to bring about the offspring that is the world of AE (time). The realm of AE is the realm of the Necessary. (Dialogue Timaeus 50-52 which occurs the following morning after the night of Republic) | D. Intellection (Noesis): Noesis is often translated by “Mind”, but “Spirit” might be a better translation. Knowledge (γνῶσις, νοούμενα) intellection, the objects of “reason” or the logos (Logoi) (νόησις, ἰδέαι, ἐπιστήμην). “Knowledge” is permanent and not subject to change as is “opinion” whether “true” or “false” opinion. Opinions develop from the pre-determined seeing which is the under-standing of the essence of things. |

| C. Forms (Eide): Begotten from the Ideas (ἰδέαι) . They give presence to things through their “outward appearance” (ousia). There is no-thing without thought; there is no thought without things. Human being is essential for Being. Being needs human being. “And would you also be willing,” I said, “to say that with respect to truth or lack of it, as the opinable is distinguished from the knowable, so the likeness is distinguished from that of which it is the likeness?” | C. Thought (Genus) Dianoia is that thought that unifies into a “one” and determines a thing’s essence. The eidos of a tree, the outward appearance of a tree, is the “treeness”, its essence, in which it participates. We are able to apprehend this outward appearance of the physical thing through the “forms” or eide in which they participate. Understanding, hypothesis (διανόια). The “hypothesis” is the “standing under” of the seeing that is thrown forward, the under-standing, the ground. |

| B. The physical things that we see/perceive with our senses (ὁρώμενα, ὁμοιωθὲν) | B. Trust, confidence, belief (πίστις) opinion, “justified true beliefs” (δόξα, νοῦν). Opinion is not stable and subject to change. The changing of the opinions that predominate in a community is what is understood as “revolution” or “paradigm shifts”. “Then in the other segment put that of which this first is the likeness—the animals around us, and everything that grows, and the whole class of artifacts.” |

| A. Eikasia Images Eikones: Likeness, image, shadow, imitation, our vision (ὄψις, ὁμοιωθὲν). The “icons” or images that we form of the things that are. The statues of Dedalus which are said to run away unless they are tied down (opinion). It is the logoi which ‘ties things down’. | A. Imagination (Eikasia): The representational thought which is done in images. Our narratives, myths and that language which forms our collective discourse (rhetoric). Conjectures, images, (εἰκασία). The image of a thing of which the image is an image are things belonging to eikasia. We are “reminded” of the original by the image. “Now, in terms of relative clarity and obscurity, you’ll have one segment in the visible part for images. I mean by images first shadows, then appearances produced in water and in all close-grained, smooth, bright things, and everything of the sort, if you understand.” The Platonic “imagination” is distinguishable from the “transcendental imagination” of Kant. For Kant, the “transcendental imagination” refers to a “blind yet indispensable function of the soul” which is responsible for synthesizing sensory data into coherent experiences (logos) making the objects of experience possible (eros). Human consciousness and self-awareness is both sensibility/sense perception and understanding, and the “transcendental imagination” transforms mere sensations into conscious perceptions. Here, Kant is speaking about the ‘form’ that ‘informs’ i.e. technology. Like Kant, for Plato the imagination is not merely reproductive but is productive in that it makes experience, in general, possible through the coming together of the logos and eros. Unlike Kant, for Plato Eros is not “blind”. |

See also https://mytok.blog/2023/08/18/platos-divided-line-and-the-golden-mean/