A few notes of warning and guidance before we begin:

The TOK essay provides you with an opportunity to become engaged in thinking and reflection. What are outlined below are strategies and suggestions, questions and possible responses only, for deconstructing the TOK titles as they have been given. They should be used alongside the discussions that you will carry out with your peers and teachers during the process of constructing your essay.

The notes here are intended to guide you towards a thoughtful, personal response to the prescribed titles posed. They are not to be considered as the answer and they should only be used to help provide you with another perspective to the ones given to you in the titles and from your own TOK class discussions and research. You need to remember that most of your examiners have been educated in the logical positivist schools of Anglo-America and this education pre-determines their predilection to view the world as they do and to understand the concepts as they do. The TOK course itself is a product of this logical positivism.

There is no substitute for your own personal thought and reflection, and these notes are not intended as a cut and paste substitute to the hard work that thinking requires. Some of the comments on one title may be useful to you in the approach you are taking in the title that you have personally chosen, so it may be useful to read all the comments and give them some reflection.

My experience has been that candidates whose examples match those to be found on TOK “help” sites (and this is another of those TOK help sites) struggle to demonstrate a mastery of the knowledge claims and knowledge questions contained in the examples. The best essays carry a trace of a struggle that is the journey on the path to thinking. Many examiners state that in the very best essays they read, they can visualize the individual who has thought through them sitting opposite to them. To reflect this struggle in your essay is your goal.

Remember to include sufficient TOK content in your essay. When you have completed your essay, ask yourself if it could have been written by someone who had not participated in the TOK course (such as Chat GPI, for instance). If the answer to that question is “yes”, then you do not have sufficient TOK content in your essay. Personal and shared knowledge, the knowledge framework, the ways of knowing and the areas of knowledge are terms that will be useful to you in your discussions.

Here is a link to a PowerPoint that contains recommendations and a flow chart outlining the steps to writing a TOK essay. Some of you may need to get your network administrator to make a few tweaks in order for you to access it. Comments, observations and discussions are most welcome. Contact me at butler.rick1952@gmail.com or directly through this website.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B-8nWwYRUyV6bDdXZ01POFFqVlU

A sine qua non: the opinions expressed here are entirely my own and do not represent any organization or collective of any kind. Now to business…

The Titles

- For historians and artists, do conventions limit or expand their ability to produce knowledge? Discuss with reference to history and the arts.

The first essay title asks us to define and understand what “conventions”, “limitations” and “expansion”, “the ability to produce”, and what “knowledge” is in the arts and history. Examining these terms closely will help the student to get their bearings within the areas of knowledge of history and the arts and of the perspectives from which the questions unfold from out of those areas of knowledge.

First of all, the title indicates that “knowledge” is something that is able to be “produced”. To “produce” is “to make” or to “bring forth”, to bring into existence something from out of materials or components that are ready-to-hand and already in existence. To “produce” can also mean “to cause or bring about a result”. This “causing” indicates that something is responsible for an end result.

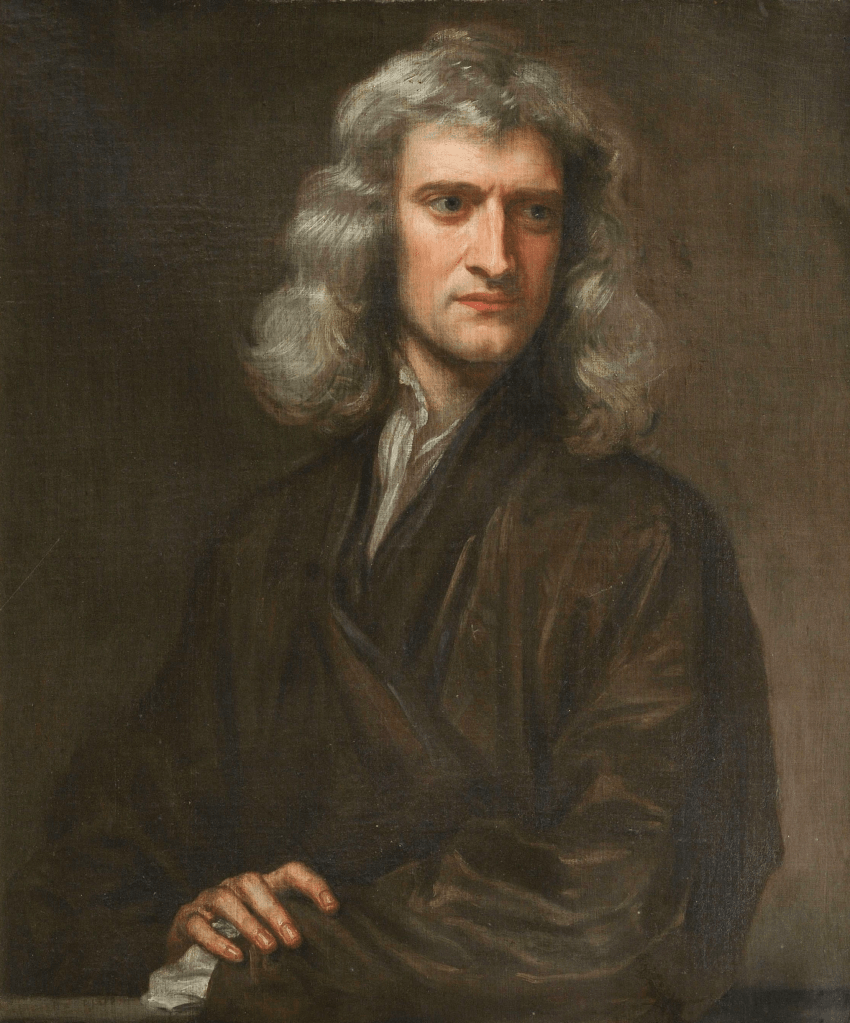

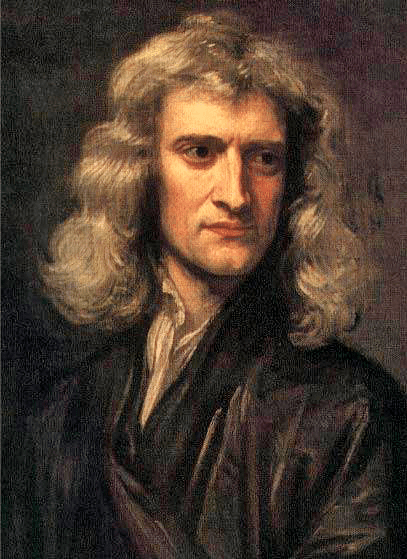

For example, if we look at our word “information”, we will see that its suffix is “-ation” which derives from the Greek aitia meaning “that which is responsible for”. So the word “in-form-ation” may be said to mean “that which is responsible for the “form” so that it has the ability to “inform”. The “form” that was responsible for creating the ability to “inform” was called logos by the Greeks. We translate logos as “reason” or “rationality”, a type of thinking. When Albert Einstein complained to Werner Heisenberg that “God does not play dice”, Einstein’s position was based on his belief that the universe was ‘rational’, a “conventional” belief that he had inherited from Newton’s physics. The conventions of science are expressions of the ‘faith’ based on our belief in the axioms and principles of mathematics and how they relate to Nature.

The ‘forms’ of our thinking are what we understand as the ‘conventional’. The conventional from this thinking is where we get our “knowing”. “Making” and “knowing” is our word “technology”: techne being the craft of the artist, the artist’s “know-how”, the “making”, and logos being the “knowing” itself, that which allows the “making” to be possible. The “knowing” or logos establishes that “open region” that allows for the making of the tools of technology such as computers and handphones. “Information” is a type of knowledge that has been ‘brought forth’, and for many it is the only form of knowledge.

“Conventions” are the “opinions” of the many and they will always be found to be surrounded by politics, particularly in History, but also in the Arts. They provide the horizons, the limits, in which understanding and meaning are given to human beings in their lives. In our being-in-the-world, we are at the same time living in a number of “sub-worlds”. You are an IB student or teacher, but this is only one of a number of worlds that you occupy simultaneously and each of these worlds has a different logos with which you are familiar and within which you are “at home”. Other human beings live in other sub-worlds in which you are not at home because you lack the logos or the ‘expertise’, the “know-how” required to fit comfortably within that world.

For our title, the sub-worlds are the worlds of the arts and history, and each of these worlds has a specialized vocabulary that distinguishes those who live in these sub-worlds. Each of these sub-worlds has a logos which is unique to itself and the purpose of education is to provide the learning so that one may be able to enter into the various ‘sub-worlds’ or areas of knowledge as a ‘specialist’ and to be able to dwell comfortably and be ‘at home’ in that world . “Conventions” are the ways and the contents of the knowing that provide the base of understanding that allows one to enter into a sub-world. They are the sub-world’s “history”. They provide the horizons or limits within which the sub-world operates. When one decides to operate outside of the conventions of the sub-world, one will then use ‘imagination’ or ‘fantasy’ to do so. These two types of ‘thinking’ are not the same.

The AOK of History attempts to deal with a world of “facts”; and from that limited world, the logos or perspective of the historian builds from an understanding, which is given to him/her from “convention”, how those facts are to be interpreted, selectively choosing and shaping the meaning of those ‘facts’ into a ‘rational’ whole or form so that others may come to understand the significance of the events being discussed. History deals with the past, present, and future. Its concern is with Time. The purpose of studying history is to gain knowledge of the actions of others in the past so that we in turn will gain self-knowledge so that we can come to an understanding of our place in history so that we will be able to make ‘informed’ decisions in the future. In order for history to inform us, some ground rules must be followed in its telling. This is what is known as ‘convention’, and ‘convention’ is both limiting and at the same time liberating.

The historian relies on ‘rationality’ as that which brings the ‘facts’ to light to show them in their “truth”. The first historian of the West, the Greek Thucydides, wrote: “I have written my work, not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time.” History of the Peloponnesian War bk. 1, Ch. 22, sect. 18 (tr. Richard Crawley, 1874) Thucydides is saying that while his work is history, his writing of that history is “trans-historical”. His work rises beyond the rhetoric that is the logos of those who wish to gain fame in the present. He believes that his work will have something to say to those who wish to understand the essence of war and of power and so be able to ‘interpret’ these phenomenon in the future. Such knowledge will possibly prevent future cataclysms. His history outlines the end of that era known as the Periclean or Golden Age of Greek history due to the failure of the Athenians’ war against the Spartans. If Thucydides is right, reading his history should be helpful for us if we wish to understand the essence of, say, the USA at this moment in its politics. Thucydides is a ‘true historian’.

The propagandist, on the other hand, relies on ‘fantasy’, the ‘big lie’, the gaslighting that questions the reality of the facts themselves and is, thus, the ‘false historian’. Since we have ‘facts’ as a reality, we also have ‘interpretations’ of facts. The propagandist limits himself in the interpretation of facts by his lack of imagination or thoughtlessness. The interpretations of facts is the discourse of historians. Thucydides believes he has gotten to the ‘truth’ of the facts in his interpretation that is a product of his understanding. His truth ‘defines’ or places limits on the things which he is speaking of so that they can be understood, brought forth, and be capable of being spoken about. He must convey this truth through language (which is also another meaning of the Greek term logos) providing sufficient reasons for his interpretation of the things he has chosen to speak about.

The propagandist’s view, however, is “unlimited” according to the rules of convention for his view relies on ‘fantasy’, and fantasy is opposed to ‘rationality’ and to the ‘imagination’. The propagandist will not have evidence or sufficient reasons to support his perspectives on the facts that he has chosen. The propagandist is ‘anti-rational’ and abhors thinking in any form for thinking gives light to the lie that he is trying to propose. The propagandist requires thoughtlessness. Defining the propagandist as ‘anti-rational’, one can go so far as to say that the propagandist speaks the ‘insane’, the ‘irrational’ to the insane and irrational. The propagandist requires the ‘unlimited’ and the ‘unconventional’. Truth brings the facts to light. The lie obscures, hides, deceives and does so in an irrational logos. The end purpose of the lie is the achievement of power i.e. it is political, and all writing is finally political for it involves our being-with-others and our speaking to others. This is the reason why propagandists appeal to the ‘anti-rational’ emotions of the many to achieve their ends. The propagandist relies on the emotion of the moment, while the true historian attempts to rely on the timelessness of truth. The propagandist ultimately has no respect for his audience; and since this is the case, there can be no “expansion” of knowledge.

In the USA today, the “unlimited” is shown by those who believe that they are capable of living in the various sub-worlds that have been constructed without having the specialized logos required for true participation in those sub-worlds, for being ‘at home in’ those sub-worlds. They lack the techne, the know-how or skill required. They are like poor cobblers who bring forth nothing but ill-fitting shoes. One may think one has “knowledge” where, in fact, none exists. (See the quotation from Plato’s Laws noted below).

The most famous quote of Thucydides not only applies to geo-politics, it also applies to the actions of individual human beings: “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” (History of the Peloponnesian War bk. 5, Ch. 89) The philosopher Nietzsche once said “Power makes stupid”, and this “stupidity” rests on the lack of self-knowledge that the “strong” exhibit in their lack of respect for conventions and laws. The propagandist has no ethics or morals and his will to power leaves nothing but wastelands in its wake. Thucydides’ quote applies to both individual human beings and to states.

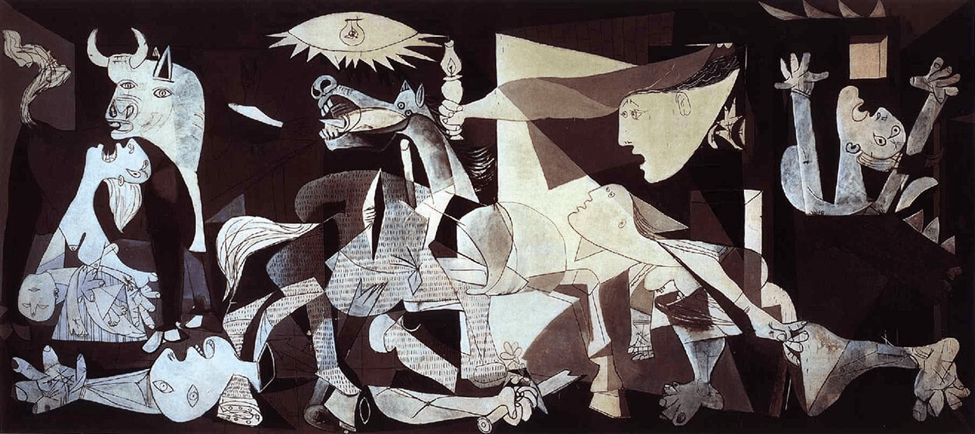

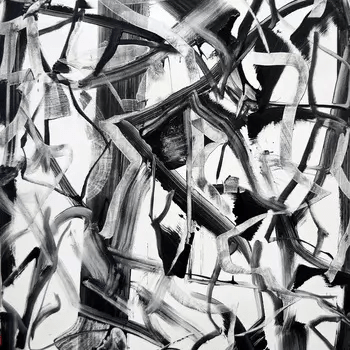

Where ‘fantasy’ rules and dismantles the role of convention providing the illusion of ‘freedom’ in the ‘unlimited’ worlds of the propagandists, ‘imagination’ is the faculty that rules over the worlds of the arts. Fantasy and the imagination are not the same thing. “Novelty” is the end for “production” in the arts (“that which is responsible for”: -tion aitia; for that which is brought forth: pro forward, ducere to lead). “Novelty” is the bringing forth of the Same even though it may be considered “new”: a shoe is a shoe is a shoe. The ‘true artist’, like the ‘true historian’, attempts to change the way in which we view our human condition, to bring about a new or fresh perspective on the things that are. In our cobbler and shoe analogy, the true artist attempts to change the manner in which we view our feet!

Both fantasy and the imagination relate to our manner of viewing the world in which we live and give us our understanding of that world. How we first see our world will determine what can or will be brought forth from that world. (See Title #2) We cannot have hand phones and computers without first viewing the world “technologically”, and our viewing provides a space for the tools of technology to come into being, to be produced. The cobbler views a shoe differently than those who are not cobblers because he views a shoe from his techne.

The English poet William Blake speaks of the “Divine Imagination” and he contrasts it with “Newton’s sleep”. “Newton’s sleep” was Blake’s view of convention: how the principle of reason (nihil est sine ratione: “nothing is without reason”) dominated our world of understanding and thus of ‘science’ or ‘knowledge’. It was and is the way in which we view the world. Today we might think of it at its apogee, which is Artificial Intelligence.

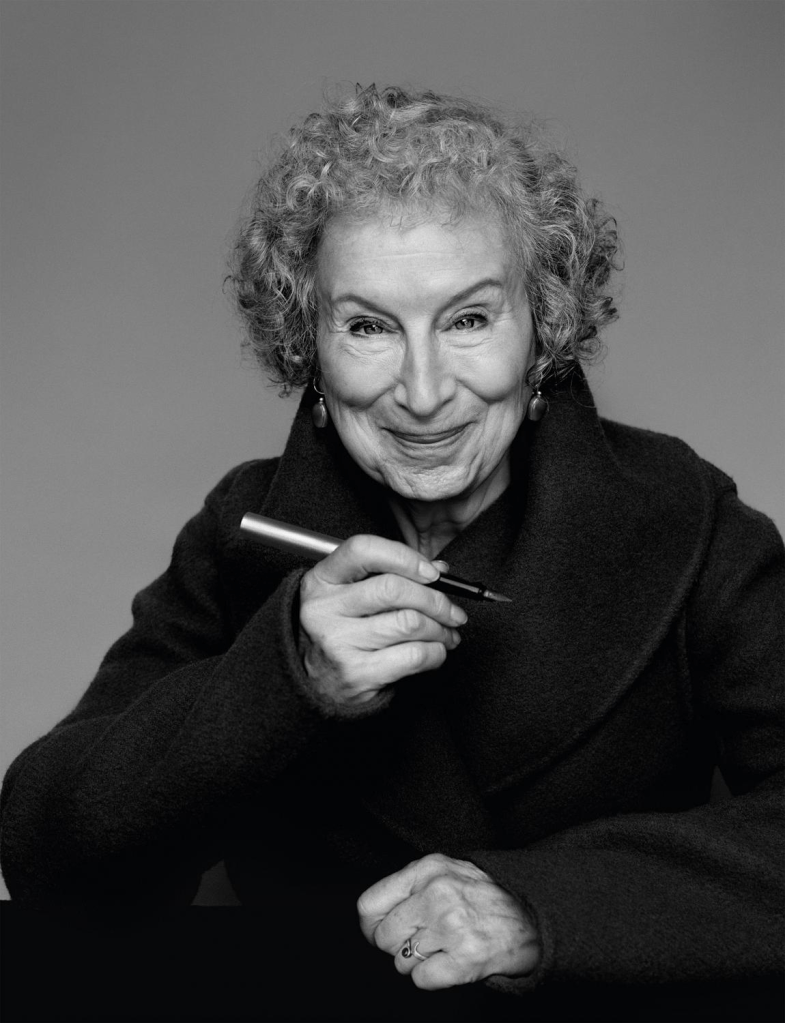

While we may view AI as ‘unlimited’ in its scope and possibilities, for an artist like Blake this is merely an illusion. Today, ‘imagination’ is a polite way of saying that something is false, and it is a common statement of the gaslighters. For Blake, however, the imagination is the central faculty of both the Divine and of human beings in contrast to ‘rationality’. Whereas the “conventional” seeing of Newton keeps us in a somnambulistic state, the imagination is all-embracing and liberating: “In your own bosom you bear your Heaven and Earth & all you behold; tho’ it appears Without, it is Within, in your Imagination, of which this World of Mortality is but a Shadow” (Jerusalem 71:17) For Blake, the imagination was the basis of all art and in the creative act, it was the completest liberty of the spirit. Many of Blake’s contemporaries thought he was ‘mad’. In Blake, the Daughters of Memory (convention, tradition) are often contrasted with the Daughters of Inspiration. “Imagination has nothing to do with memory.”

2. What is the relationship between knowing and understanding? Discuss with reference to two areas of knowledge.

(Any response to this title should also look at some of the points made in title #1 and title #3.)

For any “relationship” to be established, there must be something in common between the things that will allow that relationship to be possible. What do knowledge and understanding have in common and how are they related to each other? What do knowledge and understanding have in common with the limitations that are given within the horizons of the knowing and understanding of historians and the artists?

For the Greeks, the term metaxu is a word that means “between”, “among”, or “in the midst of”. It can also mean “meanwhile”, “in the meantime”, or “afterwards”. This ‘between’ has something to do with being and time for its meaning is adverbial in nature while also containing elements of the gerund. We could say that it is the ‘relationship’ itself that is ‘between’ knowing and understanding and dwells in the midst of what knowing and understanding are. It is a constant presence between the two and must be present for both to occur.

“Understanding” may be said to be “something in which you have a reason to believe”. It involves “faith” to some degree. Understanding may be said to precede knowledge, for there is no knowledge possible without first understanding. Understanding is “consciousness”, “awareness”. Understanding is our projection of possibilities for our being-in-the-world. Once understanding is established, one then proceeds to knowledge. Understanding is the prosthesis which allows knowledge to come to be.

Understanding is the horizons that are the limitations that are present in what is called knowledge in the areas of knowledge. Understanding is always present or ‘in the midst of’ what we call knowledge, just as knowledge is always present in how we understand some things. Understanding is the axioms or “common sense” from which we proceed to gain knowledge of some other thing. Under-standing is the grounding of our seeing, our vision, or how we view the world or worlds in which we happen to be involved. What is it that “stands under” what we think knowledge to be? How does this standing under provide a prosthesis for our moving forward in the quest for knowledge?

If for example we believe that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”, our understanding is our belief in what we think ‘beholding’ to be. The understanding is the ‘beholding’ itself. From this, the possibilities for how we understand the Arts proceeds, and our ‘knowledge’ of those Arts will be spoken of in a language which shows what we think that ‘beholding’ to be i.e. it “proceeds” from out of that beholding itself and that ‘beholding’ is a projection of its possibilities.

If we think about the word ‘behold’, we can see that it is a viewing or a looking that creates a ‘grasping’, a ‘holding’ that gives ‘being’ or reality to something: be-hold. “Viewing” or “looking” is what the Greeks understood as theoria, and our word “theatre” “the viewing place” derives from it. The theory is produced from the manner of the “looking”. For the theory to proceed from the looking, the looking must give various possibilities. When this looking provides the being to things, ‘reality’ is given to things and then knowledge of the thing is made possible. This knowledge will then be expressed in a language that arises from out of such “be-holding”, and so we see that it is language or what the Greeks called logos that is the “relationship” between knowing and understanding. We translate logos by “reason”, but it is also language or ‘word’. The manner in which we view things is given justification through the provision of evidence. We know more about the things we have made than about the things we have not made. The evidence which is required for the being or existence of things are the sufficient reasons demonstrated in the results or outcomes that have occurred.

The giving of reality or being to something is to give that thing meaning or significance. The giving of meaning is to provide the thing with “significance” for us. Where ‘significance’ is lacking, meaning is lacking and some things become overlooked or ignored because they are believed to contain no possibilities. This giving of meaning to things provides us with the ‘know how’ that allows us to occupy our worlds securely. This is done through the axiom of the principle of reason (“Nothing is without a reason”). An axiom is a statement or proposition which is regarded as being established, accepted, or self-evidently true. It is based upon “faith”. It is the foundation of the area of knowledge we understand as mathematics. Mathematics is “that which can be learned and that which can be taught” i.e. the projected “possibilities” of reason. The axioms of mathematics are the logoi that derive from the principle of reason, “that which is thrown forward”. “Mathematical projection” is the realization of the possibilities of the things which we encounter in our day-to-day lives.

A principle is much like an axiom. It can be a fundamental truth or rule that serves as a basis for something i.e. a prosthesis, an under-standing, a support. Principles can be used in various contexts including science, ethics, and everyday life; for example, “The principle of relativity” in physics or “The principle of fairness” in ethics. Principles are statements that can be derived from observation, experience, or other principles, unlike axioms which are statements based on the self-evidently true. “Statements” are what we understand as the logoi, which is the relation between what is said about the thing and the thing said. We understand this saying about things as “judgement”.

“-Logy” is a suffix that follows the naming of many of our areas of knowledge e.g. “bio-logy”, “psycho-logy”, etc. That the self-evidently true can be ignored is shown in USA’s Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Such a statement expresses a “faith” that can provide the motive or motion for an action that is an expression of a “belief” if it is taken to be true. If not taken to be true, it can simply be ignored. Self-evident truths are often ignored in our day-to-day lives if they are not convenient for us. This is particularly so in Ethics and Politics.

Through understanding, we disclose the meaning and the significance of the entities (things) and the experiences that we have not by simply knowing facts but by grasping their significance within the context of our being-in-the-world. Language is the fundamental tool for understanding as it allows us to express and share our experiences and interpretations of the world (the whole) and the worlds of which we are a part, the contexts and details that make up the experiences of our lives. In its broadest sense, language can be understood as both word and number. The axioms of mathematics and the rational discourse of the principle of reason are both “relationships” between knowing and understanding that are established by the logos be it word or number.

3. Should knowledge in an area of knowledge be pursued for its own sake rather than its potential application? Discuss with reference to mathematics and one other area of knowledge.

A well-known gangster saying has it that ‘Blood is very expensive and bad for business.’ In the world of academic research for its own sake, “Truth, like blood, is very expensive and bad for business”. The poet John Keats once wrote: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all/ Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

In mathematics, as well as in many other areas of knowledge, those who are engaged in ‘pure mathematics’ do so because they find that what they do (the pure disinterested use of number) fills them with a sense of the overwhelming beauty of the world. The ‘true’ mathematician and the ‘true’ artist are engaged in what they do because of the beauty of what they encounter through their work. This encounter with beauty fills their lives with joy. In Sanskrit, the word is ananda or “bliss”. We may say that this encounter is the experience of the relationship between knowledge and truth and how truth illumines the reality of the world which the mathematician or artist inhabits (its beauty). The mathematician or artist will always be tempted by the ‘big bucks’ on offer for the ‘practical applications’ of the knowledge that they have. They have the choice to succumb to that temptation or to remain true to their ‘faith’. This choice is not an easy one for the simple reason that one needs to eat.

The propagandist, be they an historian or an artist, abhors the truth for the truth seeks to bring things to light while the propagandist wishes to hide the truth for it is a threat to his real interest, which is power. This power manifests itself most often in public prestige often showing itself in the form of money. Human being, in its nature, reveals truth. When it does not do so, it becomes ‘inhumane’. Corporate interests and their propagandists (their media advertisers) are not interested in truth or education since their end is to produce the mass society of mass consumption, the ‘city of pigs’ as it was designated in Plato. The artist who designs the media campaigns for the large corporations is not a true artist just as the historian who works as a gaslighter for political entities is not a ‘true’ historian since he does not report the truths as they relate to the facts.

Earlier, I spoke of the English poet William Blake’s identification of the thinking of the scientist with what he called “Newton’s sleep”. For Plato (and Blake), science does not think in the way that thinkers think. This is science’s blessing for if it did think in the manner in which thinkers think we would cease to have all of the wonderful discoveries that science’s applications have produced. The thinking required to combat the general “thoughtlessness” of the sciences is not the kind of thinking that is to be found in the sciences. The thinking upon which the sciences are grounded is a form of nihilism since it is the principle of reason, the science itself, that gives being or reality to things. Elon Musk’s thinking, for example, is not the thinking of a thinker. It is the thinking of a technician. What is it that distinguishes the thinking of a technician from the thinking of the philosopher?

In Plato, the ideas give being to the things that are and cause them to come to appearance in their ‘outward form’ (eidos). The ideas are the logoi be they “word” or “number”, and the ideas as number are distinguished from the ones, twos and threes that we usually think of as numbers in our calculations. The ideas as “word” are different from our usual understanding of “words, words, words” as ‘information’. The thinking of the technician or the artist uses the ‘imagination’ or eikasia in order to enable his ‘know how’ or ‘technical skill’, his techne, to construct the product or end that he has in mind and bring that product into being be that product a pair of shoes or a poem. In the Divided Line of Plato from Bk. VI of his Republic, B=C: the ‘material world’ (B) is equal to that world that we understand through rational thought (C). Rational thought (C) is capable of ‘procreating’ an infinity of possibilities within the sempiternal character of created Nature (B). This is what we understand by ‘materialism’. There will always be new Nikes as there will always be new poems, but neither creation will be ‘great’. It will be the procreation or the bringing into being of the Same.

The knowledge that we understand as episteme or ‘theoretical knowledge’ is dependent on, and in a relation to, the higher section of the Divided Line that Plato outlines in Bk. VI of his Republic (D:C). Socrates (534 a 4-5) relates that dialectical noeisis, “the conversation between two or three that runs through the ideas, is to pistis (faith, trust, belief) as natural and technical dianoia is to eikasia (imagination).” Socrates distinguishes the logos of the ‘spirit’ or nous that is used by the ‘dialectician’ from the logos of the imagination which is that used by the technician and the artist. The numbers and words of the ‘spirit’ are distinguished from the numbers and words of the creative artist and technician. For example, Socrates did not write books; Plato wrote books. Jesus Christ did not write books; his followers wrote the books. The Buddha did not write books; his followers wrote the books. These writings of the followers were the products of the “imagination”. They represented a knowledge of the individual (Socrates, Christ, the Buddha) that was a product of a gnosis or ‘direct experience’ of the individual; but in the writing this knowledge becomes ‘true opinion’, an ‘interpretation’.

The ideai are the logos: the ideas give to things their essence, their ‘whatness’, and thus their being, while the eidos (whether of word or number) gives them their “outward appearance”. The ideas are not the products of human beings but something which has been given to human beings. They are much like the axioms which we discussed under title #2. We have come to call these outward appearances of things “beauty”. The “outward appearance” of the thing is merely its ‘shadow’ i.e. it is the thing without its ‘light’, its logos, and it is its light (truth) which illuminates its truth and its ‘true beauty’. (That is why the Sun is a metaphor of the Good in the allegory of the Cave). According to Plato, the thinking which seeks the essences of things is that “noetic thinking” that we have come to call ‘geometry’. Geometry is now what we understand as ‘spacial relations’ between things but Plato understood ‘geometry’ as the possibility of the thing being brought into a relation of ‘harmony’ and friendship.

Over his academy Plato had the statement, “No one enters unless he knows geometry.” By this he meant that no one enters (gains knowledge) unless he knows “friendship” and is capable of friendship, of relationships. This knowledge of friendship is a gnosis or a knowing by direct experience and is a by-product of that self-knowledge which allows one to have the capability of being a friend.

The natural dianoia or ‘gathering together into a one’ which is the product of scientific rationalism (the turning of the thing into an object), is a ‘mirroring’ of that thinking that is dialectical noeisis. The “seeing” for one’s self becomes a ‘hearing’ from others on the ‘method’ or ‘plan’ that is to be used to bring about a desired result. While it is not knowledge as gnosis or direct possession or experience it, nevertheless, is ‘true opinion’. The distinction is shown in the example of the road to Larissa in the dialogue Meno of Plato where one has been given correct instructions on how to get there but has not personally undertaken the journey for themselves: if one follows the directions, one will get to Larissa.

The ‘should’ of the title implies an ethical choice: the humanity of human beings always implies ethical choices; they are what make us ‘humane’. If scientists thought the way that thinkers think, then we would not have the many wonderful discoveries that science has been able to produce through its applications, its techne. If the poet Keats is correct, then these discoveries have some ‘beauty’ in them and, therefore, truth. They are part of our ‘humaneness’.

The writings of a Plato and a Blake are not the usual writings that have been given to us. The ‘creativity’ of a Blake and a Plato, their use of the imagination, is different: their art leads to that thinking and that direct experience of beauty and truth which is not the product of the imagination. But the Blakes and Platos, like the philosophers and saints, are few and rare among us.

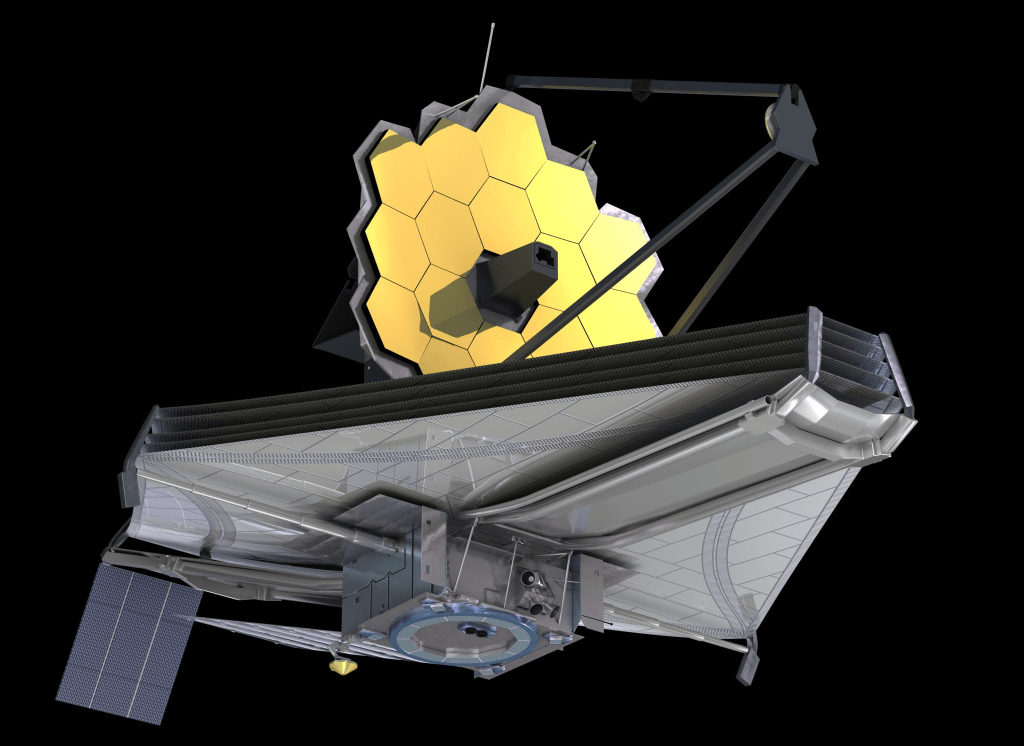

4. To what extent do you agree that however the methods of an area of knowledge change, the scope remains the same. Answer with reference to two areas of knowledge.

“Methods” may be said to be a particular form of procedure for accomplishing or approaching something, especially a systematic or established one such as the ‘scientific method’. Historically, the scientific method is said to have been given to us by the English materialist Francis Bacon. “Methods” are among some of the ‘conventions’ spoken of earlier in these essay titles particularly title #1. The “scope” is the “seeing” or “viewing”. A micro-scope means “to see small”; a tele-scope means “to see far”. The “scope” is what produces the theoria, the theory that determines how one is to see in a certain manner. The “scope” is what gets things going in an area of knowledge and determines the theories that arise from within it.

The answer to the question, for example, “why has algebraic calculation become the paradigm of knowledge for our times” (the “mathematical projection” that results in the “to what extent” type of questions that we ask) is not a proposition: it reveals a transformed basic position, a transformation in the “scope”, or a transformation of the initial existing position of human beings towards things, a change of questioning and evaluation, of seeing and deciding, a transformation of what we are as human beings and what we think we are as human beings in the midst of what is. This transformation is a true paradigm shift and it occurred during the transformation of the age known as the Renaissance to that known as the Age of Reason in the West. In the William Blake example used here, it occurs is the ‘cruel materialism’ of the English philosopher John Locke, the science of Isaac Newton, and the method of Francis Bacon.

We cannot use science to tell us what science itself is: we cannot conduct an experiment or use the other methodologies of the sciences to teach us what science itself is. The question concerning our basic relations to nature (including our own ‘human nature’, our own bodies), our knowledge of nature as such, our rule over nature is itself in question in the question of how we stand in relation to all the things that are. This questioning will lead to the ‘abyss’, and our response to our questioning can only come through discussions that will make us mindful of the implicit assumptions which we hold with regard to what we call knowledge.

In connection with the historical development of natural science, things become objects, material, and a point of mass in motion in space and time and the calculation of these various points. When what is is defined as object, as object it becomes the ground and basis of all things, their determinations as to what they are, and the kinds of questioning that determine those determinations. This grounding is the mathematical projection and we may call this grounding a “knowledge framework”. This “knowledge framework” itself is grounded in the principle of reason: nothing is without a cause, or nothing is without reason (reasons).

The determination of things as objects is the “scope” of our projection of things. That which is animate is also here in this determination of object: nothing distinguishes humans from other animals or species (Darwin’s Origin of Species). Even where one permits the animate its own character (as is done in the human sciences), this character is conceived as an additional structure built upon the inanimate. This reign of the object as material thing, as the genuine substructure of all things, reaches into the area that we call the “spiritual”, into the sphere of the meaning and significance of language, of history, of the work of art, and all of the areas of knowledge of TOK. It is what we call our culture. Works of art, poems and tragedies are all perceived as “things”, and the manner of our questioning about them is done through “research”, the calculation that determines why the “things”/the works are as they are. The difficulty from such a position is that while we may learn about the thing that we call history, for instance, we cannot learn from the thing that we call history because we perceive ourselves to be in a superior position to it from the outset.

When the “scope” of what and how we are attempting to gain knowledge changes, then we have what we call a true “paradigm shift” in the study of what we have been historically observing. The German physicist Heisenberg once said: “What we observe is not nature in itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning. Our scientific work in physics consists in asking questions about nature in the language that we possess and trying to get an answer from experiment by the means that are at our disposal.” When quantum physicists study laser light to try to understand its properties, it is not a thing of nature that they are studying. Laser light does not occur naturally. Why is the knowledge arrived at in the Natural Sciences considered to be “knowledge” in its most “robust” form and what is it knowledge of then? Technology is the “scope” of what we have come to call knowledge and it is technology which provides the “space” for the objects and methodologies of technology to come into being.

To characterize what modern technology is, we can say that it is the disclosive looking (the scope) that disposes of the things which it looks at. Technology is the framework that arranges things in a certain way, sees things in a certain way, and assigns things to a certain order: what we call the mathematical projection. The “looking” (the theory) is our way of knowing which corresponds to the self-disclosure of things as belonging to a certain order that is determined from within the framework itself. From this looking, human beings see in things a certain disposition; the things belong to a certain order that is seen as appropriate to the things i.e. our areas of knowledge.

The seeing of things within this frame provides the impetus to investigate the things in a certain manner. That manner is the calculable. Things are revealed as the calculable. Modern technology is the disclosure of things as subject to calculation. Modern technology sets science going; it is not a subsequent application of science and mathematics. “Technology” is the outlook on things that science needs to get started. Modern technology is the viewing/insight into the essence of things as coherently calculable. Science disposes of the things into a certain calculable order (the knowledge framework as based on the principle of reason). Science is the theory of the real, where the truth of the things that are views and reveals those things as disposables.

The “scope” or the idea that nature is a calculable framework of forces stands at the beginning of experiments, or prior to the experiments, and is not the result of experiments. Galileo’s rolling of balls down an inclined plane does not result in a view of nature as calculable forces; Galileo must first see, must first have the “theory” in view in advance of what he believes that things in general are like.

The grounding of this theory, this looking, the “scope” is beautifully encapsulated in the title of Newton’s great work Philosophae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which we translate The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. “Natural Philosophy” is science of nature or what we call knowledge. Modern science must possess this disclosive looking, these mathematical principles or axioms, before it sets to work, before it conducts experiments. In the light of this mathematical view, science devises and conducts experiments in order to discover to what extent and how nature, so conceived, reports itself. Experimentation itself cannot discover what nature is, what the essence of nature is, since a conception of the essence of nature is presupposed for all experimentation. Without the conception of nature in advance, the scientist would not know what sort of experiments to devise.

The rigor of mathematical physical science is exactitude. Science cannot proceed randomly. All events, if they are at all to enter into representation as events of nature, must be defined beforehand as spatio-temporal magnitudes of motion. Such defining is accomplished through measuring, with the help of number and calculation. Mathematical research into nature is not exact because it calculates with precision; it must calculate in this way because its adherence to its object-sphere (the objects which it investigates) has the character of exactitude. In contrast, the Group 3 subjects, the Human Sciences, must be inexact in order to remain rigorous. A living thing can be grasped as a mass in motion, but then it is no longer apprehended as living. The projecting and securing of the object of study in the human sciences is of another kind and is much more difficult to execute than is the achieving of rigor in the “exact sciences” of the Group 4 subjects.

Today’s word for “method” is algorithm. An algorithm is based on the principle of cause and effect and the principle of contradiction, both of which come together under the principle of reason. The grounds of any algorithm are the algebraic calculations projected onto a world conceived as object, including the human beings who occupy that world. A method may be said to be the application of the principle of reason (which is the “scope”, the “seeing” that is the understanding: see Title #2), which provides the form for the orderliness of thought or behavior or the systematic planning that precedes action. This is what is understood here as the logos. We speak of the ‘experimental method’. All of these may be broadly understood as ‘logistics’ for they centre on providing the efficiency and accuracy necessary for our technological way of being-in-the-world. When we think of our word “information”, we see that it is composed of in-form-ation: that which is responsible for the “form” (-ation from the Greek aitia) so that it may “inform”. Without the form, which is the logos, it cannot inform. The “form” is what we call the “mathematical” and this is what the Greeks understood as one aspect of logos as it is used in these writings.

5. In the pursuit of knowledge, is it possible or even desirable to set aside temporarily what we already know? Discuss with reference to the natural sciences and one other area of knowledge.

Should we decide or attempt to ‘set aside’ what we already know for any period of time would indicate that we desire that we are not ‘conscious’ for that period of time i.e. we are without any understanding of our world we live in and thus are ‘machine-like’, motion without consciousness. Such a position is ‘thoughtless’ and as should be clear from the earlier discussions on these titles, it is a position not possible for human beings. There is always an a priori understanding of the world in which we live and this a priori understanding will determine how we will view that world.

In earlier titles I spoke of the English poet William Blake’s notion of “Newton’s sleep” and indicated that it was the kind of thinking that was done in the rational (natural) sciences for it focuses on the material world and fails to take into consideration the ‘spiritual’ or ‘noetic’ realm of the world inhabited by human beings. Blake spoke of the ‘cruel philosophy’ of materialism that had spread from England throughout the world: “I turn my eyes to the Schools & Universities of Europe and there behold the Loom of Locke, whose woof rages dire, wash’d by the Water-wheels of Newton: black the cloth in heavy wreathes folds over every Nation.” (Jerusalem 15:14) In the painting of Newton by Blake, we can see that Newton writes upon a scroll which proceeds or ‘projects’ from the back of his head. He does not do his calculations upon a rock tablet or in a book (which come to establish the conventions spoken about in title #1), and such writing upon a scroll is indicative of “imaginative creation” which is from the realm of eikasia in Plato’s Divided Line from Bk VI of his Republic which was discussed under title #3. The “imaginative creations” of the artists and technicians create the objects that are paraded in front of the fire in Plato’s allegory of the Cave.

In Blake, “Newton’s sleep” is that ‘unconsciousness’ which arises from a materialistic mechanistic conception of the world; and in Blake’s mythology, this materialistic conception is comprised of the triune figures of Newton, Bacon, and the English philosopher John Locke. This trinity of figures of naturalistic rational science, or empirical science, are opposed to the creative figures of John Milton, Shakespeare and Chaucer in Blake’s mythological world. Both the scientific and poetic figures use the logos whether as number or word in order to construct their creations or projections. With Newton, we have the law of gravity for instance, while with Shakespeare we have King Lear.

The understanding, which makes a tabula rasa position impossible in the pursuit of knowledge, is the “projection of possibilities” onto the world in which we live. We call such projections “projects”, so we speak of the “mathematical project”. To pro-ject is “to throw forward”, into the future. The outcome is to be anticipated in the future. In the Blake painting, the “project” is the scroll which is thrown forward and upon which Newton is doing his calculations. Our desire to “overlook” or “skip over” what we already know comes from our urge towards “novelty”, the “new”, in our desire to create. This desire for the new proceeds from the possibilities that are already present in our initial projection. (See response to title #1) The initial projection or understanding ensures that the results from such ‘new’ creations will always be the Same.

In the natural sciences, the theory of relativity of Einstein is not a new “projection” of physics but, rather, stands upon the shoulders of Newton and what are called “classical physics”. The other great discovery of modern physics, the indeterminacy principle of Heisenberg, also stands upon Newton’s shoulders but it is a much more radical rejection of Newton’s findings and calculations. With our new technologies, we are discovering that Heisenberg’s calculations have a greater precision and exactness than the findings of Einstein.

The natural sciences deal with the world as a “surface phenomenon”, their physical presence. As a surface phenomenon, the natural sciences deal with the world in which we live as a ‘power phenomenon’ and that world’s meaning lies in the relations of these manifestations of force. The workings of the artist also deal with the world as a ‘surface phenomenon’ but in doing so attempt to get at the ‘depth’ of the physical object that they are trying to portray. Both the natural scientist and the creative artist use the imagination to make representations of the phenomenon of which they wish to speak in order to convey the ‘essence’ or truth of the phenomenon. Such use of the imagination will be determined by thinking in which the artist or technician is engaged in their manner of seeing and understanding their worlds.

6. Is empathy an attribute that is equally important for a historian and a human scientist? Discuss with reference to history and the human sciences.

The French philosopher Simone Weil once wrote: “Faith is the experience that the intelligence is illuminated by Love.” I have spent a good part of my life trying to understand what she meant by that. Empathy is part of love; we cannot love unless we have empathy for that which we encounter in our everyday being-in-the-world. Empathy is one of the bridges that we have to overcome our experience of the world as separate from ourselves. Empathy is a self-conscious awareness of the feelings, experiences, and emotions of the other human beings around us.

In relation to the other titles discussed here, “empathy” is a part of a state of consciousness that is of a higher order than rationality. It requires a state of some self-consciousness or self-knowledge on the part of the individual involved. Empathy is distinguished from sympathy in that one can be sympathetic towards another’s condition without feeling any empathy for that individual at all. Empathy is an emotion which helps overpower the subject/object distinction that dominates modern technical thinking. Sympathy is an emotion of superiority while empathy is not and we are quite capable of sympathy even though we may be in a position of power.

The difficulty for the historian and the human scientist is that they must cease to be “scientists” if they wish to have “empathy” for that which they are studying or researching because that which they are studying and researching must first be turned into an object; and in both of these specific cases, the objects that are being studied are other human beings. The objects of their study need to be enframed within a statistical matrix so that an answer to the “to what extent” type of questions can be put forward. The “objects” of study must be “dead” in a very real sense.

The researchers, whether in history or the social sciences, must observe the fact/value distinction: the fact-value distinction suggests that facts are objective and values are subjective, and that values cannot be derived solely from facts. The great danger for historians when they do not observe the fact/value distinction is that they can become mere propagandists for their vision is dominated by the empathy they feel towards “one’s own”. As the dictator Josef Stalin said: “Only the victors get to write the history.” Social scientists merely become ‘morally obtuse’ in their political recommendations due to their reluctance to recognize something as ‘good’ or ‘evil’, or good or bad. The historians and social scientists must attempt to rise above that subjectivity that stresses that “one’s own” is the “otherness” that is the world in which we live.

What we believe “science” or “knowledge” to be is founded upon or grounded in the understanding that is the subject/object distinction: that we know more about something by turning the thing into an object and making it “useful” and “disposable” to us and for us in some way. In history and the social sciences, this requires the use of the fact/value distinction since these sciences have always tried to mirror the natural sciences in their methodology. (See title #4)

That which distinguishes philosophers and saints (and makes them so rare and few among us) is their ability to rise beyond our very “common sense” love of our own to the love of the Good. This conflict is very much alive today in all of our encounters within our being-in-the-world and our being-with-others. Our being-in-the-world involves our constant struggle to ‘know ourselves’ and to know what is ‘good’ for ourselves. Our being-with-others involves politics, and politics involves power.

In the USA, Pope Francis made a pointed critique of J. D. Vance’s erroneous exposition on medieval theology regarding the ordo amoris, the ‘ladder of love’ or the ‘steps of love’ which were originally outlined by Diotima the prophetess in Plato’s Symposium. Vance stated: “There is a Christian concept that you love your family; and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country. And then after that, you can focus and prioritize the rest of the world.” In the X post, he called his view “basic common sense.” Of course, Vance has left out ‘the love of self’ which is prior to all of the steps that he has outlined. The love of self that lacks ‘self-knowledge’ colours all of the subsequent viewings of family, community, country and world.

The ordo amoris initially outlined by Diotima in Symposium is about the order of love and the justice that is due all human beings which involves caring and concern for all in need. This care and concern arises from an ’empathy’ for all human beings. It involves the distinction between love as eros and love as agape. To quote from the Pope’s letter, “The true ordo amoris that must be promoted is that which we discover by meditating constantly on the parable of the ‘Good Samaritan’ (cf. Lk 10:25-37), that is, by meditating on the love that builds a fraternity open to all, without exception. But worrying about personal, community or national identity, apart from these considerations, easily introduces an ideological criterion that distorts social life and imposes the will of the strongest as the criterion of truth.” The Pope added, “What is built on the basis of force, and not on the truth about the equal dignity of every human being, begins badly and will end badly.” The question which needs to be explored is what is it about human beings that makes justice (“equal dignity”) their due and what are the consequences for human beings when this equal justice is not upheld? How does this relate to love of one’s own and love of the Good?

Plato in his Laws indicates the problem of an overreaching “love of one’s own”: “For the lover is blind to the faults of the beloved, so he is a poor judge of what’s just and good, because he believes he should always honour his own, above the truth. But a man who is to be a great man must cherish, not himself or what belongs to himself, but what’s just, either in his own actions or indeed in the actions of others. From this same fault is born the universal conviction that our own ignorance is wisdom, and so we who, in a sense, know nothing, imagine that we know everything. And since we don’t rely on others to do whatever we ourselves don’t know, we inevitably make mistakes in doing this ourselves. That’s why everyone must flee from this intense self-love, and always keep with someone better than himself, without feeling any shame in doing so.” The Laws (731D-732B)

Human beings are by nature empathetic. When human beings lose their ’empathy’, they become inhumane, bestial. Justice is the recognition of “otherness”, and this sense of otherness begins with empathy. The tyrant is the most unjust of human beings because his/her sense of “otherness” has all but disappeared. Macbeth is the best example of this that we have in our literature, and his “Tomorrow and tomorrow…” speech (Act V sc. v) indicates the nihilism that befalls all those who succumb to the tyranny of their own injustice or lack of a sense of otherness. Macbeth’s speech is by someone who is incapable of learning from history, and so for him, life has come to have no ‘significance’. Life is “a tale/ Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury / Signifying nothing.” This view is that which is held by a person who has violated life’s laws; nevertheless, it is a view held by many today.

Today, Elon Musk’s actions in the USA indicate a similar lack of recognition of otherness and a similar lack of recognition of the thinking that is necessary for justice, what the Greeks understood as phronesis or “good judgement”. “Empathy” is lacking in his actions and his thinking. As the philosopher Nietzsche noted: “Power makes stupid”; and stupidity leads to arrogance and the other hubristic failings that prevent human beings from achieving arete or “human excellence”. Musk, who many consider a ‘great thinker’, a ‘genius’, is incapable of the thinking that is exercised by the philosophers and the great artists and his recent actions have caused the whole of his thinking to become questionable.

Plato’s discussion of the Divided Line which occurs in Bk VI of his Republic distinguishes between the thinking that is done by philosophers and the thinking that is done by technicians and artists . In Bk VI, the emphasis is on the relation between the just and the unjust life and the way-of-being that is “philosophy”. Philo-sophia is the love of the whole for it is the love of wisdom which is knowledge of the whole. The love of the whole and the attempt to gain knowledge of the whole is the call to ‘perfection’ that is given to human beings. Since we are part of the whole, we cannot have knowledge of the whole. This conundrum, however, should not deter us from seeking knowledge of the whole and, indeed, this seeking is urged upon us by our erotic nature. All human beings are capable of engaging in philosophy, but only a few are capable of becoming philosophers. As human beings, we are the ‘perfect imperfection’. While the top of the mountain may be obscured in clouds, we are still able to distinguish a mountain from a molehill and so we are able to reach beyond that thinking or consciousness that is the fact-value distinction.